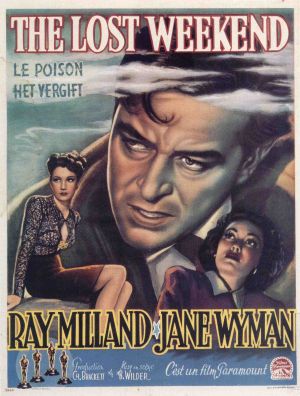

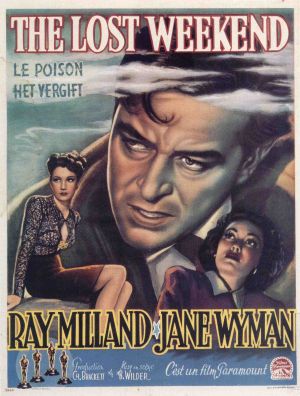

In the seminal August 1946 article which coined the expression ‘film noir’, French film-critic Nino Frank referred to five Hollywood movies as noirs: The Maltese Falcon (1941), Double Indemnity (1944), Laura (1944), Murder, My Sweet (1944), and The Lost Weekend (1945). By coincidence in the same month, expatriate German cultural critic, Siegfried Kracauer, who had moved to America because of WW2, in Commentary magazine argued that Hollywood films like Shadow of a Doubt (1942), The Lost Weekend (1945), and The Stranger (1946), displayed a certain decadence.

In the first book on film noir, A Panorama of American Film Noir, 1941-1953, published in France in 1955, the authors, Raymond Borde and Étienne Chaumeton, say that The Lost Weekend was only superficially a film noir, because “strangeness and crime were absent”. In Andrew Spicer’s Film Noir (2002), The Lost Weekend does not rate a mention, and it does not merit an entry in Silver and Ward’s Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference (1992).

To my mind Billy Wilder’s The Lost Weekend is unequivocally a film noir. The film has a definite noir sensibility and explores the dark themes of existential angst and entrapment. While the story arc is about an alcoholic’s weekend bender which spirals out on to the edge of desperate criminality, and the portrayal of alcoholic addiction was strong enough for the liquor industry to offer Paramount a cool five million dollars to bury the picture, the underlying theme is the angst of failure, of being trapped in a life without purpose or meaning. Ray Milland is Don Birnam, a failed writer, hanging on a thread like the bottle of Rye hidden and hanging on a cord outside his bedroom window, and nothing can more powerfully express his life than when he tells his girl, Helen, why he drinks (and this excerpt from the script is testimony to the power of the screenplay penned by Wilder and long-time collaborator, Charles Brackett):

DON:

A writer. Silly, isn’t it? You see, in college I passed for a genius. They couldn’t get out the college magazine without one of my stories. Boy, was I hot. Hemingway stuff. I reached my peak when I was nineteen. Sold a piece to the Atlantic Monthly. It was reprinted in the Readers’ Digest. Who wants to stay in college when he’s Hemingway? My mother bought me a brand new typewriter, and I moved right in on New York. Well, the first thing I wrote, that didn’t quite come off. And the second I dropped. The public wasn’t ready for that one. I started a third, a fourth, only about then somebody began to look over my shoulder and whisper, in a thin, clear voice like the E-string on a violin. Don Birnam, he’d whisper, it’s not good enough. Not that way. How about a couple of drinks just to put it on its feet? So I had a couple. Oh, that was a great idea. That made all the difference. Suddenly I could see the whole thing – the tragic sweep of the great novel, beautifully proportioned. But before I could really grab it and throw it down on paper, the drink would wear off and everything be gone like a mirage. Then there was despair, and a drink to counterbalance despair, and one to counterbalance the counterbalance. I’d be sitting in front of that typewriter, trying to squeeze out a page that was halfway

decent, and that guy would pop up again.

HELEN:

What guy? Who are you talking about?

DON:

The other Don Birnam. There are two of us, you know: Don the drunk and Don the writer. And the drunk will say to the writer, Come on, you idiot.

Let’s get some good out of that portable. Let’s hock it. We’ll take it to that pawn shop over on Third Avenue. Always good for ten dollars, for another drink, another binge, another bender, another spree. Such humorous words. I tried to break away from that guy a lot of ways. No good. Once I even bought myself a gun and some bullets. (He goes to the desk) I meant to do it on my thirtieth birthday. (He opens the drawer, takes out two bullets, holds them in the palm of his hand.)

DON:

Here are the bullets. The gun went for three quarts of whiskey. That other Don wanted us to have a drink first. He always wants us to have a drink first. The flop suicide of a flop writer.

WICK [Don’s brother]:

All right, maybe you’re not a writer. Why don’t you do something else?

DON:

Yes, take a nice job. Public accountant, real estate salesman. I haven’t the guts, Helen. Most men lead lives of quiet desperation. I can’t take quiet desperation.

To complete the potent formula you have the cinematography of the great John F. Sietz, art direction by the brilliant Hans Dreier, and a deeply evocative score from Miklós Rózsa. Sietz’ fluid and lengthy takes, and moodily lit interior shots add depth to the ‘caged’ mise-en-scene of Don’s apartment: evoking a sense of desperation when Don ransacks the place searching for a bottle of Rye; and then terror at night when the DT’s take hold. On the streets of Manhattan, Sietz’ camera is in deep focus on harsh sun-lit streets of empty desperation where a staggering Don searches for an open pawn shop on Yom Kippur. Drieir elegantly furnishes Don’s tenement apartment with bookcases, sofas, lamps, and wall-hangings that disguise the places where he hides his booze. Rózsa’s score is persistent and dramatic, and he innovatively uses the early electronic instrument, the theremin, to produce an eerie and sinister motif for Don’s affliction.

Milland’s performance is masterful and he carries the picture. Cast against type, his tranformation from a clean-shaven everyman to a dishevelled drunk hallucinating in a darkened room, where his eyes betray the depth of his obsessed decline, is fully dramatic in it’s intensity. Jane Wyman as Helen, only comes into her own in the finale after she has lost a leopard-skin coat and her hair is wet and loose after being in the rain. Minus the coat and her perm she is a sensual and liberating influence. To Wilders’ and Brackett’s credit, the ending while positive remains open-ended: a relapse is just as likely as Don actually writing the great unfinished novel. A solid contribution is made by b-actors Howard Da Silva and Doris Dowling. Da Silva plays a sympathetic bartender who is a father-confessor figure ironically dispensing shots of rye instead of Hail Maries. Dowling, who played the murdered wife in The Blue Dahlia (1946), is particularly engaging as a b-girl who is soft on Don. Veteran noir supporting actor, Frank Faylen, has a short but memorable appearance as a male nurse in a hospital drunks clinic. This harrowing sequence is shot in true noir style and with a frankness that works brilliantly to enlarge the drama from the particular to the social. The only weakness is a wooden portrayal of Don’s straight-laced brother.

This brings me to a particularly intriguing element in The Lost Weekend. Don is not a lecherous drunk: his desire for booze sublimates all other appetites, but interestingly Wilder weaves a stunning sexual frankness into the photoplay. The b-girl Gloria works out of Stan’s bar, and the nature of her work is up-front and personal. The male nurse, Bim, in the detox clinic is clearly gay, and his sermonising on the evils of drink has a surreal even sinister quality.

Early in the movie in an interlude told in flashback Wilder’s sardonic humor takes center stage. Don is at the Opera, and all on stage are drinking champagne. The whole sequence plays as a liquor ad tempting Don to leave the performance and try and grab hold of a bottle of rye in the pocket of his checked-in overcoat.

A great Hollywood picture and a true noir.