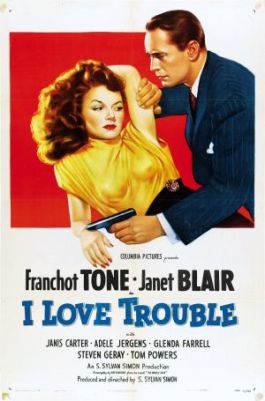

This is one-helluva-movie. A gem that sparkles like the eyes of the hot dames that swagger, pout, smolder, and snap their high heels across the screen. A joyous LA romp in Marlowe territory which has it all. An enthralling thriller plot enlivened by a hot-jive script from Roy Huggins (Too Late for Tears, Pushover). Incredibly taught and fluid direction from Columbia b-director S. Sylvan Simon. Superb noir photography from Charles Lawton Jr. A dynamic score from George Duning that sways effortlessly from dark melodrama to lecherous winks.

A great turn by Franchot Tone as LA private eye Stuart ‘George’ Bailey, who out-Bogart’s and out-Powell’s Philip Marlowe in a deliciously convoluted story of deception, greed, frame-ups, murder, and sexy high jinks. Bit player Glenda Farrell is a comic delight as Bailey’s cute, loyal, eccentric, and sharp-as-nails secretary Hazel. Tom Powers delivers a solid performance as the aging suspicious husband who hires Bailey to tail his young wife, who is being blackmailed. Steven Geray delivers a nuanced low-key performance as mysterious crime-boss Keller, and John Ireland, Raymond Burr, and Eddie Marr are great as Keller’s heavies. Sid Tomack is in his element as a small-time chiseller who is out of his league. The dames are all delightfully buxom good-bad girls, with enough charm and innuendo for a dozen Marlowes: Janet Blair, Janis Carter, Adele Jergens, Lynn Merrick, and Claire Carleton. A weird waitress-from-hell played by uncredited bit-player Roseanne Murray, is a scream.

There are laughs and smooth-as-nylons repartee, but the melodrama is hard-hitting and typically noir: guys get slapped hard, drugged, and slugged from behind. In one scene the face of a murder victim under a Malibu pier is highlighted by torch-light at night. A particularly impressive scene is where a guy is under the threat of a gun, which is shown from the holder’s viewpoint, as it moves with the frightened target as he staggers backward and across the screen in a small room.

What is particularly captivating is the on-street location-shooting that gives the whole picture a verite-look. From daylight scenes in the streets of LA to available light scenes at night in dives, suburban streets, and dark alleys in industrial areas. There is one daylight road scene where Bailey is being followed by another car, and he manoeuvres his car to dramatically confront his pursuer, and then gives chase. The positioning of the camera and the elegant panning as each car careens across the screen make the sequence one of the most exciting I have seen.

A must-see noir. Sadly not yet available on DVD.