GEORGE HURRELL (American, 1904-1992):

Category: Actors

Sidney Falco checks out: Vale Tony Curtis (1925-2010)

Tony Curtis’ best role has to be the sleazy publicist Sidney Falco in Alexander Mackendrick’s acid noir Sweet Smell of Success (1957). Burt Lancaster’s manipulative NY celebrity columnist enlists the amoral Falco to destroy his younger sister’s suitor. These guys are as bracing as vinegar and cold as ice: ambition stripped of all pretense. The chemistry between Lancaster as the sinister chat columnist and Tony Curtis as the ruthless publicist is palpable. It is also DP James Wong Howe’s sharpest picture – the streets of Manhattan have never looked so real.

The Subversive Truth of Noir: The Glass Wall (1953)

I was fed-up I guess

In the still-topical and very off-beat noir, The Glass Wall (1953), about post-war refugees and the nature of true compassion, Gloria Grahame gives a richly delicate performance as a young woman on the skids who helps a desperate asylum-seeker played with obvious sincerity by Vittorio Gassman. The streets of New York are rendered with a stunning chiaroscuro palette by DP Joseph Biroc. While the direction by Maxwell Shane could have been tighter, he also had a hand in the excellent script. A gem worth seeking out.

The Big Clock (1948): “the wrong people always have money”

The Big Clock opens with the dark silhouette of skyscrapers against a New York night with bordello jazz on the soundtrack. After a pan tensely edging right across the screen, the camera rests on and zooms into the mezzanine level of a modernistic office building with the signage ‘Janoth Publications’. An anxious man in a suit narrowly avoids a security guard as he sneaks into the mechanism of a large clock that dominates the foyer below. His voice-over relates the circumstances of a dire predicament and events flashback to the previous morning.

But this is about as noir as it gets. The guy inside the clock is a suave Ray Milland, a family guy working for a dictatorial publishing tycoon as the editor of Crimeways magazine. His boss is a gargoyle in a suite sporting a Hitler moustache, and with the nervous habit of sliding his flabby forefinger across his bushy upper lip. A man who knows the cost of everything and the value of nothing. Charles Laughton occupies the suit and the executive suite in a building of apt fascist modernist lines fashioned by the film’s art director, Hans Drier.

Director John Farrow and DP John Seitz infiltrate this place with smooth and flowing steps that despite their elegance somehow render the whole space rather flat. Office space is sterile at best, and the result is a ponderous unraveling of a story that borders on the tedious. But such spaces can be rendered with atmosphere. Look at how – and this is indeed ironic – the same Dreier and Seitz under the direction of Billy Wilder make an insurance office look interesting in Double Indemnity (1944).

To cut to the chase, Milland is being framed for a murder by murderer Laughton, who doesn’t know the true identity of the guy he is trying to frame. It sounds better than it plays out. The whole scenario is played too lightly and with no atmosphere. The source novel by Kenneth Fearing has lost something in Jonathan Latimer’s screenplay. Though the tycoon’s final misstep as he escapes into his personal elevator is savagely noir.

Thankfully the affair is saved by an uproarious turn from a supporting actress in a part that occupies less than seven minutes of screen time. British-born character actor Elsa Lanchester – Laughton’s wife and Mrs Frakenstein in the camp classic Bride of Frankenstein (1935) – is a zany bohemian painter, who by chance gets tangentially mixed-up with Milland and proceeds to steal the picture – there is a pun here you will recognise if you have seen the movie or watch the clip below. She keeps turning up and closes the movie with a neat scene of comic irony.

This is her story. She first appears in an antique shop where she and a drunken Milland in the company of the tycoon’s girlfriend haggle over a rather grotesque painting.

Noir Dames: “Don’t you love her madly?”

La Nuit du Carrefour (1932 – France): Moody and surreal!

In this early Jean Renoir film with a magically delicious femme-noir and a brilliant car chase at night, were sewn the seeds of French poetic realism that flourished later in the 30s in the films of Marcel Carné and others.

La Nuit du Carrefour is a largely faithful adaption of Georges Simenon’s gloomy pulp policier ‘Maigret at the Crossroads’. Renoir in a television introduction to the movie in the early 60s said the screenplay is deliberately episodic and the rough-edges exaggerate the obscurity of the story to create an atmosphere of mystery. A review of the film in Time Out says the rough edges come from Renoir running out of cash before completion, while a story put about by Godard says that some footage is missing. It is a moot point though as the picture is great as is.

The cinematography of Georges Asselin and Marcel Lucien is dark and brooding, with foggy rural night scenes infiltrating even interior shots. An exhilarating car-chase at night filmed from the pursuing car in real-time uses only the car headlights, and is an exemplar of the creative fusion of director, camera, and editor. The editor is Renoir’s wife, Marguerite.

In the film, a city detective investigates a murder in a small rural burg, with suspicion surrounding the strange foreign tenants of a mysterious house: a bizarre ménage comprising a stoned b-girl and her reclusive ‘brother’, who as a foreigner with a weak alibi is the immediate suspect. The girl Else, played to delicious perfection by Danish actress, Winna Winifried, steals the picture. Renoir has aptly described Else as a ‘bizarre gamin’. You want Else to be in every scene – she is stunning and her turn is so lascivious. While in the book Else has more depth and is certainly less screwy, I think I prefer her screwy and sexy! Particularly memorable is the ambivalence of the relationship between Else and the detective, played by Renoir’s brother, Pierre, which is woven into the mis-en-scene with erotic abandon and casual elegance. My poetic homage to Else is here.

The story plays as a classic who-done-it, but by the end the veneer of the bucolic ville is stripped away to reveal a rotten reality where almost all residents, both workers and bourgeois, are complicit in a drug-trafficking racket, that segued into murder over the loot from a jewel heist. The irony is that the early suspect, Else’s brother, is innocent, while Else has been trapped by her past into a forced complicity that will see her released from jail early.

If you like your noir dark, sexy, mysterious and sharply witty, go for it!

Winna Winifried in Renoir’s La Nuit du Carrefour (1932): “a bizarre gamin”

For Else

Stoned, immaculate

Siren for a delicious purgatory

a wanton butterfly she flutters wings that beckon

to a bed of lurid bliss

She mopes she languishes she swoons

she formulates a trajectory to the stars

from the milky way of her bosom to the glistening ivory of her ice cold thighs

A gambit for a gentle trap so you can fall into a warm moist grotto

and shut her doe eyes with kisses four

She does not leave you by a cold hill side

but caresses your tongue in her luscious mouth

her lips labia that clasp a deep penetration

and hold you transfixed

She leaves you a broken wreck

panting for more

You beg for

just a glimpse

An insolent glare has you shuddering

you want her to incinerate you with those eyes

incendiary transports to a cosmic nirvana

Her anger and petulant pout

a delirium

a narcotic –

you will expire for a fix

Until she graces her enfolding embrace over you

and sighs deep ecstatic sighs

Agony

Until she turns you to her

and you drown in a dark languid pool

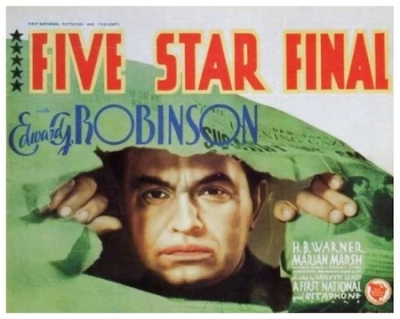

Five Star Final (1931): Down with the bosses!

The great Edward G. Robinson is the hard-boiled editor of a big-city tabloid. The owner of the paper comes up with the idea of boosting circulation by pursuing a lurid expose on the fate of a woman convicted of a crime of passion 10 years earlier, with tragic consequences. Directed by the distinguished Mervyn LeRoy, Five Star Final is an early Warner ‘social protest’ movie, and the sort of movie that epitomises the pre-Code talkies: sharp dialog, sexual innuendo, irreverent satire, and social criticism. While the picture is marred by the stagy treatment of the melodrama involving the family destroyed by the tragedy that ensues, the immensity of the tragedy and its putrid genesis sustain a powerful and still relevant narrative. Boris Karloff is a hoot as an amoral ‘undercover’ reporter: Edward G. calls him “the most blasphemous thing I’ve ever seen”.

But is it a film noir? I think there are sufficient noir elements to sustain a strong case: the theme of the corrupt brutality of ‘business’, individual entrapment, the futility of trying to escape a dark past, and a downbeat ending.

The final three minutes are brilliant.

Allotment Wives (1945): The main squeeze is a dame!

A title that conjures up sordid images doesn’t disappoint. A b-programmer from Monogram co-produced by and starring the sublime Kay Fancis as a crime-boss in one of her last roles, Allotment Wives is really a late gangster flick. The organisers of the San Francisco’s Roxie Theatre coming noir series, I WAKE UP DREAMING: The Haunted World of the B Film Noir, have stretched the envelope by including this feature. Though others no doubt will pull out the tired arguments: the emasculating femme-noir threatening male dominance during the War, and the eroticisation of violence.

“Nice shooting…”

The story of a woman who uses her social status and ill-gotten wealth to front a bigamy racket where dames marry multiple GIs during WW2 to skim the allotment support paid by the Defense Dept to spouses of men on active duty, is predictable but well-made with a snappy script. Noir regular Paul Kelly as an army investigator is disappointingly wooden and his performance is underwhelming at best. Otto Kruger is fine as the lady boss’ right-hand man. The climax is brutal with Francis plugging a dame without qualm or remorse, but justice triumphs in the end. Francis’ flamboyant hats and her hair-do add a juicy camp quality to the goings-on.

Kiss Me Deadly’s Maxine Cooper Dead at 84

Maxine Cooper, the actress who played the off-beat secretary to Ralph Meeker’s Mike Hammer in Robert Aldrich’s cult noir, Kiss Me Deadly (1955), died aged 84 on April 4.

More from the LA Times.