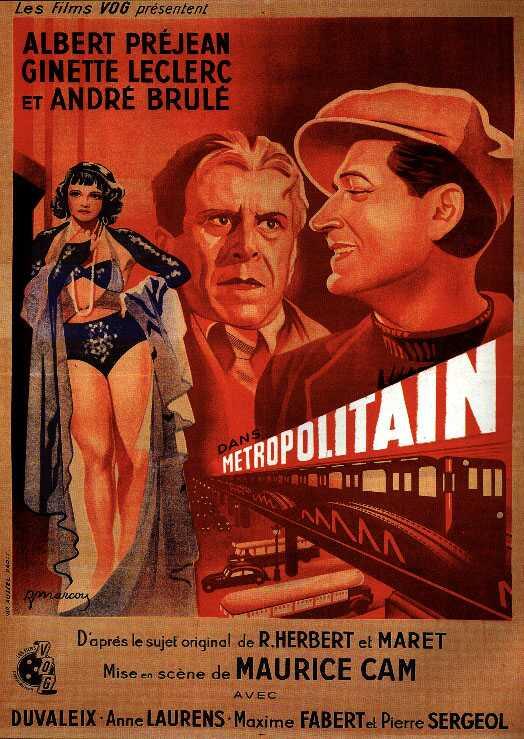

A hot poster from France for an early and earthy French noir:

FilmsNoir.Net – all about film noir

the art of #filmnoir @filmsnoir.net | Copyright © Anthony D'Ambra 2007-2025

A hot poster from France for an early and earthy French noir starring the gorgeous Ginette LeClerc as a cabaret dancer…

A hot poster from France for an early and earthy French noir:

They stopped making noir movies over 60 years ago, but the books on film noir keep on coming… and capsule reviews of four classic noirs

They stopped making noir movies over 60 years ago, but the books on film noir keep on coming. A slew of new titles will be published before year’s end:

Gloria Grahame, Bad Girl of Film Noir: The Complete Career

Robert J. Lentz

Binding: Paperback

Release Date: July 5th, 2011

In Lonely Places: Film Noir Beyond the City

Imogen Sara Smith

Binding: Paperback

Release Date: July 5th, 2011

The Maltese Touch of Evil: Film Noir and Potential Criticism (Interfaces: Studies in Visual Culture)

Richard L. Edwards & Shannon Clute

Binding: Paperback

Release Date: December 13th, 2011

What Is Film Noir?

William Park

Binding: Hardcover

Release Date: September 16th, 2011

Noirs I have recently watched – those marked with an * be added to my list of essential noirs (!):

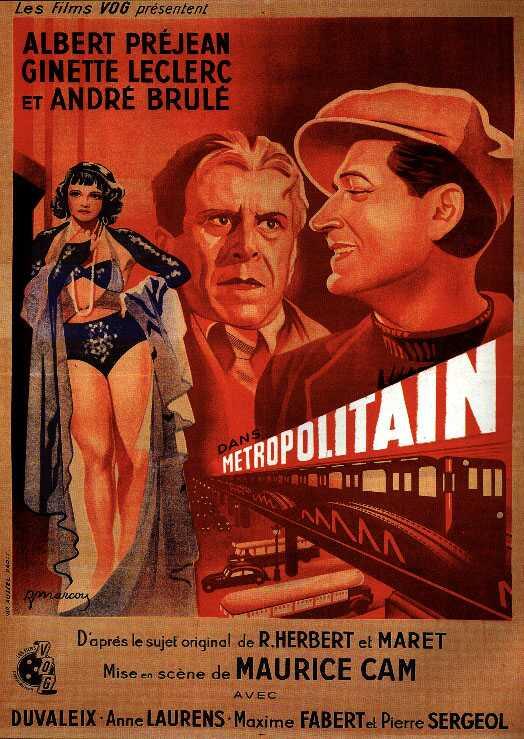

Des gens sans importance (People of No Importance – France 1956)

French fatalism meets neo-realism in a tragic story of working-class life. A long-haul trucker falls for an aimless young waitress from a road-side café. Great acting from Jean Gabin and the earthy Françoise Arnoul. 4½ stars

Senza pietà (Without Pity – Italy 1948) *

Black GI and a local girl on the skids in a doomed love triangle cannot escape tragic entrapment. Compelling neo-realist melodrama with a decidedly noir denouement. 4½ stars

Riso Amaro (Bitter Rice – Italy 1949)

Classic neo-realist socialist melodrama. Homme-fatale destroys a passionate innocent. A bad girl is redeemed and homme-fatale meets a gruesome noir end in an abattoir. 5 stars

Guele d’Amour (Ladykiller – France 1937) *

A fatalistic tale of amour-fou fuelled by a callous femme-fatale. Hunk Jean Gabin and the luminous Mireille Balin star. Looks decades ahead its time. 4½ stars

Klute (1971) *

Alan J. Pakula’s signature reworking of classic noir motifs in a masterly study of urban paranoia and alienation. Jane Fonda earned an Oscar for her brilliant portrayal of articulate b-girl the target of mystery psychopath. 5 stars

Behind Locked Doors (1948)

An entertaining Bud Bottiecher b-movie. PI Richard Carlson enters a sanatorium undercover to flush out a crook. A feast of metaphors for Bottiecher aficionados and good entertainment for the rest of us. Moody lensing from Guy Roe (Railroaded!, Trapped Armored Car Robbery, The Sound of Fury). 3½ stars

These are the runners-up to my listing of the best (5-star) films noirs. The combined list appears here as Essential Films Noir. The ‘almosts’ are 147 noir movies I rate as 4 or 4.5 stars…

These are the runners-up to my listing of the best (5-star) films noirs. The combined list appears here as Essential Films Noir.

The ‘almosts’ are 147 noir movies I rate as 4 or 4.5 stars. As with the all-time best noirs list, the films are listed by year of production and are not ranked.

4/4.5 star NoirsTitles with an * are reviewed on FilmsNoir.Net – list of reviews here. All movies have a snap review. |

||

| *La Chienne | 1931 | France |

| *Fury | 1936 | US |

| *Guele d’Amour (aka Ladykiller) | 1937 | France |

| *Pépé le Moko | 1937 | France |

| *La Bête Humaine | 1938 | France |

| La Jour se Lève | 1939 | France |

| *Macao,L’enfer Du Jeu (aka ‘Gambling Hell’) | 1939 | France |

| *Stranger on the 3rd Floor | 1940 | US |

| *Blues in the Night | 1941 | US |

| *High Sierra | 1941 | US |

| *The Face Behind the Mask | 1941 | US |

| *Ossessione | 1942 | Italy |

| *This Gun For Hire | 1942 | US |

| *The Fallen Sparrow | 1943 | US |

| *The Ghost Ship | 1943 | US |

| *Betrayed (aka ‘When Strangers Marry’) | 1944 | US |

| *Moontide | 1944 | US |

| *Phantom Lady | 1944 | US |

| *The Mask of Dimitrios | 1944 | US |

| *The Woman in the Window | 1944 | US |

| *Cornered | 1945 | US |

| *Detour | 1945 | US |

| *Fallen Angel | 1945 | US |

| *Leave Her to Heaven | 1945 | US |

| *My Name Is Julia Ross | 1945 | US |

| *Black Angel | 1946 | US |

| *Deadline at Dawn | 1946 | US |

| *Decoy | 1946 | US |

| *Gilda | 1946 | US |

| *High Wall | 1946 | US |

| *Night Editor | 1946 | US |

| *Panique | 1946 | France |

| Suspense | 1946 | US |

| *The Blue Dahlia | 1946 | US |

| *The Chase | 1946 | US |

| *The Dark Corner | 1946 | US |

| *The Dark Mirror | 1946 | US |

| *The Locket | 1946 | US |

| *The Strange Love of Martha Ivers | 1946 | US |

| *The Stranger | 1946 | US |

| *Born to Kill | 1947 | US |

| Brute Force | 1947 | US |

| *Crossfire | 1947 | US |

| *Dead Reckoning | 1947 | US |

| *Desperate | 1947 | US |

| *Kiss of Death | 1947 | US |

| *Odd Man Out | 1947 | UJ |

| *Railroaded | 1947 | US |

| *The Devil Thumbs A Ride | 1947 | US |

| *The Long Night | 1947 | US |

| *The Unsuspected | 1947 | US |

| *The Woman On the Beach | 1947 | US |

| *They Made Me a Fugitive | 1947 | UK |

| *They Won’t Believe Me | 1947 | US |

| *lood on the Moon | 1948 | US |

| *Call Northside 777 | 1948 | US |

| Cry of the City | 1948 | US |

| *I Love Trouble | 1948 | US |

| *I Walk Alone | 1948 | US |

| *Key Largo | 1948 | US |

| *Kiss the Blood Off My Hands | 1948 | US |

| *Moonrise | 1948 | US |

| *Night Has a Thousand Eyes | 1948 | US |

| *Pitfall | 1948 | US |

| *Road House | 1948 | US |

| *Ruthless | 1948 | US |

| *Secret Beyond the Door | 1948 | US |

| *Senza pietà (Aka Without Pity) | 1948 | Italy |

| *The Amazing Mr. X | 1948 | US |

| *The Big Clock | 1948 | US |

| *The Iron Curtain | 1948 | US |

| *The Naked City | 1948 | US |

| *A Woman’s Secret | 1949 | US |

| *Alias Nick Beal | 1949 | US |

| *Caught | 1949 | US |

| *Follow Me Quietly | 1949 | US |

| *I Married a Communist | 1949 | US |

| *The Big Steal | 1949 | US |

| *The Bribe | 1949 | US |

| *The Clay Pigeon | 1949 | US |

| *The Man Who Cheated Himself | 1949 | US |

| *The Window | 1949 | US |

| *Whirlpool | 1949 | US |

| *Armored Car Robbery | 1950 | US |

| *Gambling House | 1950 | US |

| *Gun Crazy | 1950 | US |

| *Manèges | 1950 | France |

| *No Way Out | 1950 | US |

| *Panic In the Streets | 1950 | US |

| *Side Street | 1950 | US |

| *Tension | 1950 | US |

| *The File On Thelma Jordan | 1950 | US |

| *The Killer That Stalked New York | 1950 | US |

| *The Second Woman | 1950 | US |

| *The Tattooed Stranger | 1950 | US |

| *Union Station | 1950 | US |

| *Walk Softly, Stranger | 1950 | US |

| *Where Danger Lives | 1950 | US |

| *Where the Sidewalk Ends | 1950 | US |

| *Woman on the Run | 1950 | US |

| *Young Man with a Horn | 1950 | US |

| *Detective Story | 1951 | US |

| *His Kind of Woman | 1951 | US |

| *I Can Get It for You Wholesale | 1951 | US |

| *I was a Communist for the FBI | 1951 | US |

| *Roadblock | 1951 | US |

| *The Big Night | 1951 | US |

| *The Well | 1951 | US |

| *Tomorrow Is Another Day | 1951 | US |

| *Angel Face | 1952 | US |

| *Kansas City Confidential | 1952 | US |

| *Scandal Sheet | 1952 | US |

| *The Narrow Margin | 1952 | US |

| *The Sniper | 1952 | US |

| *99 River Street | 1953 | US |

| *Pickup On South Street | 1953 | US |

| Split Second | 1953 | US |

| *The Blue Gardenia | 1953 | US |

| *The Glass Wall | 1953 | US |

| *The Hitch-Hiker | 1953 | US |

| *Human Desire | 1954 | US |

| *Pushover | 1954 | US |

| *The Good Die Young | 1954 | UK |

| Touchez pas au Grisbi | 1954 | France |

| *Witness to Murder | 1954 | US |

| *World For Ransom | 1954 | US |

| *Bob le Flambeur | 1955 | France |

| *The Phenix City Story | 1955 | US |

| *Patterns | 1956 | US |

| *People of No Importance (aka ‘Gens san Importance’) | 1956 | France |

| The Wrong Man | 1956 | US |

| *The Killing | 1956 | US |

| *Voici le temps des assassin (aka ‘Deadlier Than the Male’) | 1956 | France |

| *While the City Sleeps | 1956 | US |

| *Elevator to the Gallows | 1958 | France |

| *Endless Desire | 1958 | Japan |

| *Tread Softly Stranger | 1958 | UK |

| Underworld Beauty (aka ‘Ankokugai no bijo’) | 1958 | Japan |

| *Odds Against Tomorrow | 1959 | US |

| *The Crimson Kimono | 1959 | US |

| *The Bad Sleep Well (aka ‘Warui yatsu hodo yoku nemuru’) | 1960 | Japan |

| Shoot the Piano Player | 1960 | France |

| Blast of Silence | 1961 | US |

| *Le Doulos | 1962 | France |

| *High and Low (aka Tengoku to jigok) | 1963 | Japan |

| *The Naked Kiss | 1964 | US |

The greatest films noir of all time. Ambitious and perhaps presumptuous. But without apology or regrets. A list of 65 movies which I rate 5-stars…

The greatest films noir of all time. Ambitious and perhaps presumptuous. But without apology or regrets.

A list of 65 movies which I rate 5-star – the top films noir. As have an aversion to rankings, my list of the best films noir is listed by year of production.

5 star Noirs Click on the title for the FilmsNoir.Net review |

||

| La Nuit de Carrefour | 1931 France |

Aka ‘Night at the Crossroads’. Early Jean Renoir poetics. Magically delicious femme-noir and a brilliant car chase at night. Moody and bizarrre! |

| You Only Live Once | 1937 US |

Fritz Lang and Hollywood kick-start poetic realism! Henry Fonda and Sylvia Sidney are the doomed lovers on the run. |

| Hotel du Nord | 1938 France |

Poetic realist melodrama of lives at a downtown Paris hotel. As moody as noir with a darkly absurd resolution. |

| Port of Shadows | 1938 France |

Aka Le Quai des brumes. Fate a dank existential fog ensnares doomed lovers Jean Gabin and Michèle Morgan after one night of happiness. |

| I Wake Up Screaming | 1941 US |

Early crooked cop psycho-noir. Redolent noir motifs, dark shadows, off-kilter framing and expressionist imagery. |

| The Maltese Falcon | 1941 US |

Bogart as Sam Spade the quintessential noir protagonist. A loner on the edge of polite society, sorely tempted to transgress but declines and is neither saved nor redeemed. |

| Journey Into Fear | 1943 US |

Moody Orson Welles’ noir. Exotic locales, sexy dames, weird villains, politics, wisdom, philosophy, and a wry humor. |

| The Seventh Victim | 1943 US |

“Despair behind, and death before doth cast”. The terror of an empty existence. Brilliant Lewton gothic melodrama. |

| Double Indemnity | 1944 US |

All the elements of the archetypal film noir are distilled into a gothic LA tale of greed, sex, and betrayal. |

| Laura | 1944 US |

Gene Tierney is an exquisite iridescent angel and Dana Andrews a stolid cop who nails the killer after falling for a dead dame. |

| Murder, My Sweet | 1944 US |

(Aka Farewell, my Lovely). The most noir fun you will ever have. Raymond Chandler’s prose crackles with moody noir direction from Edward Dmytryk. |

| Mildred Pierce | 1945 US |

Joan Crawford in classy melodrama by Michael Curtiz lensed by Ernest Haller. Self-made woman escapes morass of greed. |

| The Lost Weekend | 1945 US |

‘Most men lead lives of quiet desperation. I can’t take quiet desperation.’ Ray Milland against type on a bender. |

| Ride the Pink Horse | 1946 US |

Disillusioned WW2 vet arrives in a New Mexico town to blackmail a war racketeer. Imbued with a rare humanity. |

| Scarlet Street | 1946 US |

Classic noir from Fritz Lang. Unremitting in its pessimism. A dark mood and pervading doom of devastating intensity. |

| The Big Sleep | 1946 US |

Love’s Vengeance Lost. Darker than Dmytryk’s Murder, My Sweet. Bogart is tougher, more driven, and morally suspect. |

| The Killers | 1946 US |

Siodmak’s classic noir. Burt Lancaster’s masterful debut performance in a tragedy of a decent man destroyed by fate. |

| The Postman Always Rings Twice | 1946 US |

Fate ensures adulterous lovers who murder the woman’s husband, suffer definite and final retribution. |

| Body and Soul | 1947 US |

A masterwork. Melodramatic expose of the fight game and a savage indictment of money capitalism. Garfield’s picture. |

| Brighton Rock | 1947 UK |

Greatest British noir is dark and chilling. A cinematic tour-de-force: from the direction and cinematography to top cast and editing. |

| Nightmare Alley | 1947 US |

Predatory femme-fatale uses greed not sex to trap her prey in a hell of hangmen at the bottom of an empty gin bottle. |

| Nora Prentiss | 1947 US |

Doctor is plunged into a dark pool of noir angst in a turbo-charged melodrama of tortured loyalty and thwarted passion. |

| Out of the Past | 1947 US |

Quintessential film noir. Inspired direction, exquisite expressionist cinematography, and legendary Mitchum and Greer. |

| The Gangster | 1947 US |

Hell of a b-movie. Very dark noir ‘opera’ brutally critiques the ‘entrepreneurial spirit’. Bravado Dalton Trumbo script. |

| The Lady From Shanghai | 1947 US |

Orson Welles’ brilliant jigsaw noir with a femme-fatale to die for and a script so sharp you relish every scene. |

| T-Men | 1947 US |

Mann and Alton offer a visionary descent into a noir realm of dark tenements, nightclubs, mobsters, and hellish steam baths. |

| Act of Violence | 1948 US |

Long-shot and deep focus climax filmed night-for-night on a railway platform: the stuff noirs are made of. |

| Drunken Angel | 1948 Japan |

Aka ‘Yoidore tenshi’. Kurosawa noir. A loser doctor with soul takes on the fetid moral swamp of Yakuza degradation. |

| Force of Evil | 1948 US |

Polonsky transcends noir in a tragic allegory on greed and family. Garfield adds signature honesty and gritty complexity . |

| Hollow Triumph | 1948 US |

Baroque journey to perdition traversing a noir topography redolent with noir archetypes. Audacious and enthralling. |

| Raw Deal | 1948 US |

Sublime noir from Anthony Mann and John Alton. Knockout cast in a strong story stunningly rendered as expressionist art. |

| They Live by Night | 1948 US |

Nicholas Ray’s first feature. A tragedy of Shakespearean dimensions which transcends film noir. |

| Too Late For Tears | 1948 US |

Preposterous chance event launches wild descent into dark avarice and eroticised violence as relentless as fate. |

| Bitter Rice | 1949 Italy |

Aka ‘Riso Amaro’. Classic neo-realist socialist melodrama. Homme-fatale destroys a passionate innocent. A bad girl is redeemed and homme-fatale meets a gruesome noir end in an abattoir. |

| Border Incident | 1949 US |

Subversive expressionist noir from Dir Anthony Mann DP John Alton and writer John C Higgin indicts US agribusiness. |

| Criss-Cross | 1949 US |

Accomplished noir showcased by Siodmak’s masterful aerial opening shot into parking lot onto a passing car exposing the doomed lovers to the spotlight. |

| Stray Dog | 1949 Japan |

Aka ‘Nora inu’. Kurosawa’s ying and yang take on reality informs this 5-star noir: the pursuer could as easily have been the pursued. |

| The Reckless Moment | 1949 US |

Max Ophuls takes a blackmail story and infuses it with a complexity and subtlety rarely matched in film noir. |

| The Set-Up | 1949 US |

Robert Ryan is great as washed-up boxer in Robert Wise’ sharp expose of the fight game. Brooding and intense noir classic. |

| The Third Man | 1949 UK |

Sublime. An engaging cavalcade of characters in a human comedy of love, friendship, and the imperatives of conscience. |

| Thieves’ Highway | 1949 US |

Moody Richard Conte hauling fruit to Frisco. Rich socio-realist melodrama from Jules Dassin and A.I. Bezzerides. AAA. |

| Une Si Jolie Petite Plage | 1949 France |

Aka ‘Riptide’. Iron in the soul: savage irony, withering subversion, and desolation mark the rain-sodden angst of a young man’s end. |

| White Heat | 1949 US |

Fission Noir. Taut electric thriller straps you in an emotional strait-jacket released only in the final explosive frames. |

| Breaking Point | 1950 US |

Great John Garfield vehicle with strong social subtext. Much stronger than from the same source To Have and Have Not. |

| Caged | 1950 US |

Eleanor Parker leads a great female cast in a dark women’s prison picture with a savage climax and a gutsy downbeat ending. |

| D.O.A. | 1950 US |

Gritty on-the-street in-your-face melodrama of innocent act a decent man’s un-doing. Edmund O’Brien is intense. The goons rock! |

| In A Lonely Place | 1950 US |

Nick Ray deftly explores effect of isolation, frustration, and anxiety on the creative psyche as noir entrapment. |

| Night And the City | 1950 US/UK |

Dassin’s stark existential journey played out in the dark dives of post-war London as a quintessential noir city. |

| Sunset Boulevard | 1950 US |

Wilder’s sympathetic story of four decent people each sadly complicit in the inevitable doom that will engulf them. |

| The Asphalt Jungle | 1950 US |

Quintessential heist movie transcends melodrama and noir. A police siren wails: “Sounds like a soul in hell.” |

| The Sound of Fury | 1950 US |

Great noir! Outdoes Lang’s Fury and brilliantly prefigures Wilder’s Ace in the Hole. Climactic mob scenes mesmerise. |

| On Dangerous Ground | 1951 US |

City cop battling inner demons is sent to ‘Siberia’. A film of dark beauty and haunting characterisations. |

| The Prowler | 1951 US |

Van Heflin is homme-fatale in Tumbo thriller. Director Losey is unforgiving. Each squalid act is suffocatingly framed. |

| Ace in the Hole | 1952 US |

A savage critique of a corrupted and corrupting modern mass media. Billy Wilder’s best movie. Kirk Douglas owns it. |

| Clash By Night | 1952 US |

Cheating wife Stanwyck faces the music. Fritz Lang puts sexual license and existential entitlement on trial and wins. |

| The Big Heat | 1953 US |

Gloria Grahame as existential hero in Fritz Lang’s brooding socio-realist noir critique. |

| Crime Wave | 1954 US |

Andre de Toth noir masterwork set on the streets of LA is so authentic it plays for real with each character deeply drawn. |

| Kiss Me Deadly | 1955 US |

Anti-fascist Hollywood Dada. Aldrich’s surreal noir a totally weird yet compelling exploration of urban paranoia. |

| Rififi | 1955 France |

Dassin’s classic heist thriller culminating in the terrific final scenes of a car desperately careening through Paris streets. |

| The Big Combo | 1955 US |

“I live in a maze… a strange blind backward maze’. Obsessed cop hunts down a psychotic crime boss in the best noir of 50s. |

| Sweet Smell of Success | 1957 US |

DP James Wong Howe’s sharpest picture. As bracing as vinegar and cold as ice. Ambition stripped of all pretense. |

| Touch of Evil | 1958 US |

Welles’ masterwork is a disconnected emotionally remote study of moral dissipation. Crisp b&w lensing by Russell Metty. |

| Underworld USA | 1961 US |

Fast and furious pulp from Sam Fuller. Revenge finds redemption in death up a back alley the genesis of dark vengeance. |

| A Colt is My Passport | 1967 Japan |

Aka ‘Koruto wa ore no pasupoto’. Hip acid Nikkatsu noir with surreal spaghetti-western score. |

| Klute | 1971 Japan |

Alan J. Pakula’s signature reworking of classic noir motifs in a masterly study of urban paranoia and alienation. Jane Fonda earned an Oscar for her brilliant portrayal of articulate b-girl the target of mystery psychopath. |

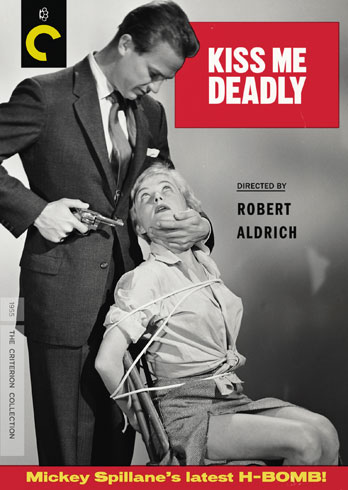

Criterion has announced the coming release of remastered prints of two major films noir on DVD and Blu-Ray

Criterion has announced the coming release of remastered prints of two major films noir on DVD and Blu-Ray: Kiss Me Deadly (1955) and Le cercle rouge (France 1970).

Kiss Me Deadly (1955) This cult classic from Robert Aldrich is a noir masterpiece and an essential relic of cold war paranoia. Totally weird and compelling. The release is scheduled for June 21. Pre-order.

Extras:

Le cercle rouge (France 1970) From the master of dark urban cool Jean-Pierre Melville. Alain Delon plays a master thief, fresh out of prison, who crosses paths with a notorious escapee (Gian Maria Volonté) and an alcoholic ex-cop (Yves Montand). The release is scheduled for April 12. Pre-order.

Extras:

Jonathan Auerbach, Professor of English at the University of Maryland and regular presenter at film noir screenings, has just published his much anticipated book on film noir, Dark Borders…

Jonathan Auerbach, Professor of English at the University of Maryland and regular presenter at film noir screenings, has just published his much anticipated book on film noir, Dark Borders: Film Noir and American Citizenship, a study which connects the sense of alienation conveyed by American film noir in the 40s and 50s with the anxieties about citizenship and national belonging in mid-20th century America, by providing in-depth interpretations of more than a dozen noir movies. Professor Auerbach shows how politics and aesthetics merge in these noirs, where the fear of subversive “un-American” foes is reflected in noirs such as Double Indemnity, Out of the Past, Border Incident, Pickup on South Street, Stranger on the Third Floor, The Chase, and Ride the Pink Horse. These anxieties surfaced during a series of wartime and post war emergency measures, beginning with the anti-sedition Smith Act (1940), the Mexican migrant worker Bracero Program (1942), the domestic internment of Americans of Japanese ancestry (1942), and the HUAC hearings in 1947.

Professor Auerbach, in 2008 in an issue of the scholarly Cinema Journal (47, No. 4, Summer 2008) in an article anticipating his book and titled ‘Noir Citizenship: Anthony Mann’s Border Incident’, posits an ambitious thesis about national borders and the borders of film genres: “Looking closely at how images subvert words in Anthony Mann’s generic hybrid Border Incident (1949), this article develops the concept of noir citizenship, exploring how Mexican migrant workers smuggled into the United States experience dislocation and disenfranchisement in ways that help us appreciate film noir’s relation to questions of national belonging.” The article offered a rich analysis of Border Incident, and developed a fascinating study of the sometimes antagonistic dynamic between the police procedural plot imperatives of the screenplay, and the subversive visual imagery fashioned by cinematographer John Alton. The scene in Border Incident where the undercover agent Jack, is murdered by the furrowing blades of a tractor is one of the most horrific in film noir, and Professor Auerbach rightly observes that the agent “gets ground into American soil by the monstrous machinery of US agribusiness… [this is] a purely noir moment of recognition that reveals the terrifying underbelly of the American farm industry itself in its dependence on and ruthless exploitation of Mexican labor”.

The paperback is available for only US$20.48 from Amazon. A great price for a book offering an original perspective that demands the attention of anyone interested in the origins of film noir.

Hollywood b-movies are a treasure trove of haunting images as arresting and poetic as any in cinema. Check out the slideshow of magic scenes from classic b-noirs…

Hollywood b-movies are a treasure trove of haunting images as arresting and poetic as any in cinema.

Check out the slideshow – move you mouse over the image for a navigation menu.

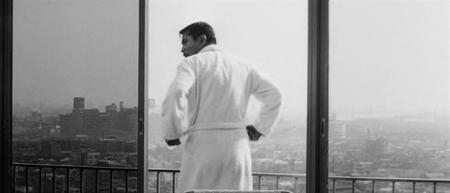

High and Low, based on American Ed McBain’s 1959 pulp thriller King’s Ransom is a noir in four acts

There are highs and lows in Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low (1963): the highs of a master film-maker and the lows that come from privileging technique over drama.

High and Low, based on American Ed McBain’s 1959 pulp thriller King’s Ransom is a noir in four acts: the crime, the investigation, the manhunt, and the confrontation. Kurosawa takes the kidnapping of a young boy as the premise for a hard-edged examination of Japanese society of the period. The film opens in the luxurious house of a shoe company director, Gondo-san, atop a hill in Yokohama overlooking the squalor of the teeming suburbs below. Floor-to-ceiling windows afford a view of a hellish suburbia while insulating his family from the noise of the burgeoning industrial metropolis.

After mortgaging all his assets to fend off a power-play from other directors, Gondo first has to face the ransom demands of a kidnapper for the safe return of his son, and then the decision of whether to pay the hefty ransom to secure the release of his chauffer’s son, who it is later revealed has been mistakenly taken for his son. The drama begins.

Act 1. The executive aerie: angst, cops, phone-calls, and wire-taps

The drapes are drawn – the kidnapper can see right into the living room from somewhere below. At one point the cops crawl on the floor when the kidnapper questions why the drapes are drawn and demands that they be opened. This establishment scenario is expertly staged and edited, but lacks tension. We have to sit through the bickering of a bunch of corporate suits for a lengthy time before the protagonists learn of the kidnapping. The scenario would have worked better with an underlying tension: move the scene where the two boys are seen to go outside and play to the start, then during the corporate shenanigans cross to a fast abduction scene – the audience knows but the protagonists don’t. Kurosawa also appears overly enamored of the wide-screen he has to play with. He fills the frame with all the characters in the room once the cops arrive. There are few close-ups of the personal drama involving Gondo, his wife, and the chauffer, as Gondo battles with the dilemma of not paying the ransom, or paying and facing financial ruin, played out in the presence of the cops who stand or sit in superfluous poses, looking away or at the floor.

Act 2. The pay-off and the manhunt

The pay-off is made from a fast-moving train in six minutes of real time and is exquisitely filmed, edited, and paced. The action then moves onto the investigation and manhunt, with the focus moving away from the family to the cops. We go from high drama to police procedural, which while convincing, goes on for far too long and in tedious detail. Thankfully, the cops while competent are drawn with engaging characters, and there is some welcome humor. Though, I wonder if a Hollywood-b would not have handled it better with more economy and a fast-paced panache.

Act 3. The net closes on the perp

An elaborate setup has the unsuspecting perp, a young cold-blooded killer, meandering through the inner-city streets of low dives and dope dens. In one scene, the fugitive, a chain-smoker in sunglasses, spots Gondo looking in a shop window and cadges a light as a cool as a cucumber. A sequence in a dance-club where the perp goes to score some heroin is brilliantly conceived, with a masterful ebb and flow as he seeks out the dealer. The action then cuts to ‘Dope Alley’ where addicts are operatically hanging out for a fix. This scene is the weakest in the movie: it is plastic and unconvincing. Though there is a certain irony with the soundtrack featuring a single piano note played at intervals.

Act 4. The confrontation

At the end Gondo is confronted with the kidnapper in a prison interview cell. The inchoate anger of the young man is rendered by a simple yet dramatic mis-en-scene. The two men are separated by a wired glass partition. Their conversation is filmed so that the active speaker is shown from the other side through the glass partition with the other man reflected in the glass.

There is a resolution but it does not provide any clear answers. Kurosawa observes more then he analyses. The perp’s motivation is not only a mystery to Gondo but to himself.

This film rewards patience and at 143 minutes also demands it. While a major work, the weaknesses are significant. Moreover, while Kurosawa’s refusal to engage with the social implications of the inequalities he explores are not seen by most critics as a weakness, I would have preferred less police procedure and more social investigation. Kurosawa’s earlier noirs Drunken Angel (1948) and Stray Dog (1949) were stronger in that regard.

Noir lifts the veil of normality to reveal the chaos below

Noir is subversive. Noir lifts the veil of normality to reveal the chaos below. The underbelly of reality. The insanity of sanity. The furtive destructiveness of obsession. The truth behind the lies. The disaster of success. The ‘ghost in the machine’.

Many of the artists of the classic noir cycle, from the writers of the hard-boiled fiction of the 20s, 30s, and 40s to those involved in the making of the films noir of the 40s and 50s, were ‘subversives’. Artists whose art was a politic statement, a social critique, a thesis on the nature of freedom and social responsibility.

Novelists like Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Ira Wolfert, Graham Greene, and Eric Ambler. Screenwriters like Dalton Trumbo, John Paxton, A. I. Bezzeridis, and Carl Foreman. Film-makers and actors like Abraham Polonsky, Jules Dassin, Orson Welles, Edward Dmytryk, Adrian Scott, Joan Scott, John Garfield, and Marsha Hunt.

A number of these artists were vilified and their careers destroyed during the ‘red menace’ years of HUAC and the blacklist. What was ignored then and largely forgotten now is that these men and women were united and largely animated by a common cause: anti-fascism. These liberals and leftists were warning of the dangers of fascism well before the outbreak of WW2, when many of the rightists that later prosecuted the anti-communist hysteria of the immediate cold-war period were apologists of fascism.

Eric Ambler was a thriller writer whose best work was written during the late 30s and early 40s. His novels Journey into Fear (1943) and The Mask of Dimitrios (1944) were made into films noir during the war. In 1938 Ambler published ‘Cause for Alarm’ – not related to any movie with the same title – a story about a British munitions engineer, Marlow, haplessly caught up in espionage in Fascist Italy. The protagonist is aided in his escape from fascist death squads by a mysterious American, Zaleshoff, who may be a Soviet spy but is definitely a socialist. Caught in a snow storm just before crossing into Yugoslavia to freedom, the pair is given shelter for the night by an artist and her elderly father. It transpires that the father is a mathematician, a Professor Beronelli, whose career was destroyed after he refused to pledge a loyalty oath to fascism. The trauma has plunged the man into insanity. The two fugitives discover this after a reviewing the professor’s notes on a perpetual motion machine, and after they realize the daughter is helping them even though she is aware of their fugitive status. After the old man goes to bed, Zaleshoff says to Marlow:

‘Sure! That’s right. What a tragedy! We’re horrified. Hell! Beronelli went crazy because he had to, because it hurt him too much to stay sane in a crazy world. He had to find a way of escape, to make his own world, a world in which he counted, a world in which a man could work according to his rights and know that there was nobody to stop him. His mind created the lie for him and now he’s happy. He’s escaped from everybody’s insanity into his own private one. But you and me, Marlow, we’re still in with the other nuts. The only difference between our obsessions and Beronelli’s is that we share ours with the other citizens of Europe. We’re still listening sympathetically to guys telling us that you can only secure peace and justice with war and injustice, that the patch of earth on which one nation lives is mystically superior to the patch their neighbours live on, that a man who uses a different set of noises to praise God is your natural born enemy. We escape into lies. We don’t even bother to make them good lies. If you say a thing often enough, if you like to believe it, it must be true. That’s the way it works. No need for thinking. Let’s follow our bellies. Down with intelligence. You can’t change human nature, buddy. Bunk! Human nature is part of the social system it works in. Change your system and you change your man. When honesty really is good business, you’ll be honest. When rooting for the next guy means that you’re rooting for yourself too, the brotherhood of man becomes a fact. But you and I don’t think that, do we, Marlow? We still have our pipe dreams. You’re British. You believe in England, in muddling through, in business, and in the dole to keep quiet the starving suckers who have no business to mind. If you were an American you’d believe in America and making good, in breadlines and in baton charges. Beronelli’s crazy. Poor devil. A shocking tragedy. He believes that the laws of thermodynamics are all wrong. Crazy? Sure he is. But we’re crazier. We believe that the laws of the jungle are allright!’

The gods, like most other practical jokers, have a habit of repeating themselves too often

The gods, like most other practical jokers, have a habit of repeating themselves too often. Man has, so to speak, learned to expect the pail of water on his head. He may try to sidestep, but when, as always, he gets wet, he is more concerned about his new hat than the ironies of fate. He has lost the faculty of wonder.

The tortured shriek of high tragedy has degenerated into a petulant grunt. But there is still one minor booby-trap in the repertoire which, I suspect, never fails to provoke a belly-laugh on Olympus. I, at any rate, succumb to it with regularity. The kernel of the jest is an illusion; the illusion that the simple emotional sterility, the partial mental paralysis that comes with the light of the morning, is really sanity.

– Eric Ambler, ‘Cause For Alarm’, London, 1938. Ambler, an English writer, wrote the source novels for the films noir Journey Into Fear (1943) and The Mask of Dimitrios (1944).