Ubiytsy (‘The Killers’ USSR – 1956)

Directed by:

Marika Beiku (Instructor)

Aleksandr Gordon

Andrey Tarkovsky

Writers:

Ernest Hemingway – short story

Aleksandr Gordon and Andrey Tarkovsky – screenplay

Cinematography by Aleksandr Rybin and Alfredo Álvarez

Cast:

Yuli Fait -Nick Adams

Aleksandr Gordon – George

Valentin Vinogradov – Hitman Al

Vadim Novikov – Hitman Max

Yuri Dubrovin – 1st Customer

Andrey Tarkovskiy – Customer

Vasili Shukshin – Ole Anderson (‘the Swede’)

Ernest Hemingway wrote The Killers, his influential short story about a Chicago mob hit, in 1927. The pared-down prose and hard-boiled dialog very much mirror the emerging pulp fiction of the period. Dashiell Hammett’s first novel, Red Dust, was published in early 1929, and W. R. Burnett’s novella Little Caeser appeared in the same year. But perhaps what distinguishes Hemingway’s story is its downbeat fatalism. A fatalism that was to emerge a few years later in the early 30s in the French poetic realist films of Marcel Carne and others, and only to emerge in Hollywood movies over a decade later in the early years of the classic film noir cycle.

Hemingway’s story is all of 10 pages long: an act in three scenes. Two loquacious hit-men enter a dinner in the late afternoon in a sleepy diner in a God-forsaken burg. They are there to kill the ‘Swede’, a guy who has a habit of having dinner at the diner around six. Nothing personal, they don’t now the guy, strictly business – and they make no secret of it – one of the hoods telling the other more than once that he talks too much. The Swede by seven has not turned up and the machinegun-toting men head out to find him. A patron called Nick that had been holed in the diner runs to the Swede’s boarding-house to warn him. The Swede is laying on his bed undecided on whether to go out, and when told of the hit-men accepts this news with weary unsurprise and then rolls-over on his bed to await his fate. Nick returns to the diner telling the owner George of the Swede’s strange reaction. The story closes with these words:

“I can’t stand to think about him waiting in the room and knowing he’s

going to get it. It’s too damned awful.”

“Well,” said George, “you better not think about it.”

This is essentially the scenario that opens the classic 1946 film noir adaptation by director Robert Siodmak, also titled The Killers. That film’s screenplay by Anthony Veiller, Richard Brooks, and John Huston (uncredited), is not so much an adaptation of Hemingway’s story, but an imaginative response and more strongly a rebuttal to one of the last lines at the end of Hemingway’s text spoken by Nick, the guy who runs from the diner to warn the Swede of the killers’ arrival: “I’m going to get out of this town”, Nick said… “I can’t stand to think about him waiting in the room and knowing he’s going to get it. It’s too damned awful”. After establishing the absolute resolve of the killers in the opening sequence, which is essentially faithful to Hemingway’s text, Siodmak’s picture ventures on to explore the burning questions in the mind of the audience. What did the Swede do to warrant this retribution? Why doesn’t he run? The Hollywood script was re-filmed in 1964 by director Don Siegel.

In 1956, the soon-to-be-great Russian film director, Andrei Tarkovsky, was a film student at the USSR State Institute of Cinematography (VGIK). As his first film project he chose Hemingway’s story. The 19 minute feature has been preserved and the very faithful adaption eloquently portrays the scenario’s underlying fatalism. I hesitate to credit the movie as a Tarkovsky effort as it is demonstrably a collaborative work where no individual dominates. The cast and crew were all VGIK students, and the sets were designed and supplied by the students. The screenplay is rightly stringent, the camera-work and editing fluid, the acting of a high order, and the direction accomplished.

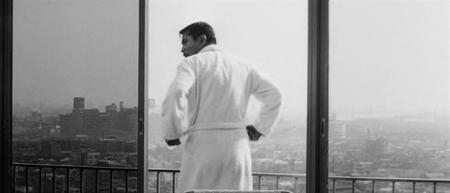

Under the guidance of instructor Marika Beiku, the film is rendered in the same three scenes from the story. The first and last scenes in the diner were directed by Tarkovsky, and the second scene in the Swede’s room at his boarding house by fellow-student Aleksandr Gordon, who also plays the diner-owner. It may be an heretical view, but I consider Gordon’s segment superior. It is shot close-up in a small room with subdued lighting and from low angles, producing a doomed claustrophobia, with an external window light producing somber shadows from a partially open-shutter. The Swede is smoking and stubs his cigarette out on the wall besides his bed, with the camera lingering in a close-up on the wall as the stub is determinedly ‘rubbed-out’.

The acting is uniformly impressive. Of course being students the cast is all young, but the intelligent casting of two baby-faced students as the two almost effete hoods was a stroke of genius. The strongest performances are by Gordon as the diner-owner and Vasili Shukshin as the Swede. Both inhabit their roles with a worthy gravitas and maturity. Gordon as both director and actor makes the diner-owner a very deep character and his presence hovers as a wounded God bereft of hope yet perhaps still clinging to a sliver of compassion for the fools that strut the stage beyond his terrestrial lunch-counter. Compare with the formulaic treatment of the diner-owner in Siodmak’s film as an inconsequential elderly ‘pop’ figure as scared as he is bewildered.

An original and essential film noir. Watch it here.