Local authorities track down violent hoods infected with a virulent infection.

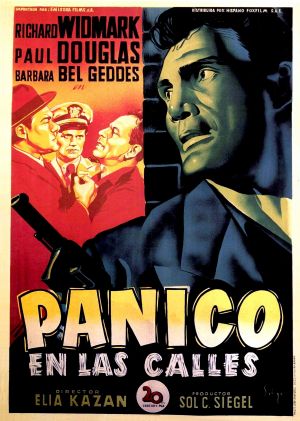

Panic In the Streets (1950) is an interesting documentary-style noir set on the docks of New Orleans: a fast-paced on-the-streets thriller with little time or inclination for deep characterisation. The movie picked up the Venice International prize in 1950, and an Oscar for Best Writing in 1951. Tautly directed by Kazan and with strong street cred: the climax on a ship’s mooring rope is elegantly metaphoric.

Richard Widmark is cast against (then) type as the local health official pushing the cops to track down the killers of an illegal alien who has infected the hoods with pneumonic plague. Paul Douglas is well-cast as the reluctant cop who heads the police task force. Jack Palance and Zero Mostel are strong as the hoods, with a certain tension between them: Palance is focused and brutal, while Mostel is nervous and obsequious. Cinematographer, Joe MacDonald, who did similar work in The Dark Corner (1946), has filmed the night scenes with moody noir atmospherics.

Given Kazan’s tendency for emotional distance and the cinema-verite approach, there is a strong social dimension to the picture. The working people in the docks milieu distrust the cops and are uncooperative, and the cops and local bureaucrats are reluctant partners. The mood is of dysfunction and the trajectory is that it is only the doggedness of Widmark and Douglas that saves the day.

All this points to Kazan’s complexity and contradictions. While those on the edge of criminal society are fairly portrayed, there is the feeling that they are stubborn and boorish, and need to be bullied by authority. At the same time, public institutions are seen at logger-heads and can only function effectively if commandeered by strong personalities.

Conventionally, Widmark and Douglas develop a grudging respect for each other and by the end of the story are friends. Strangely, this relationship for me is the core of the film, and comes not only from what happens on the screen, but also from a backward almost nostalgic perspective. Both these actors invest their roles with an essential integrity: they are not perfect, struggle financially, and their personal lives have their share of bewilderment and angst, but they are thoroughly decent men doing tough jobs, for lousy pay, and little social recognition or thanks. These guys inhabit a lost black and white world of simpler times when normal lives seemed to have greater decency. Perhaps also this perception is colored for me by Paul Douglas, a wonderful actor who always came across as a totally solid guy that you would love to have as your friend.

It was a nice little front yard.

It was a nice little front yard.

Night and the city.

Night and the city.