An amnesiac femme-fatale the titular blonde is fate’s doleful instrument in this little known neo-noir from Italian writer/director Sergio Rubini. Dark destiny takes an innocent young man with a limp and throws him onto a nocturnal autostrada littered with blood and a burst suitcase full of cash, with a woman running screaming into the night. A tragedy of gothic proportions played first as an unlikely love story takes you inexorably where so many noirs have taken us before. A blameless life and an accepting obscurity are not enough to protect the mild protagonist from a wild furiously indifferent universe.

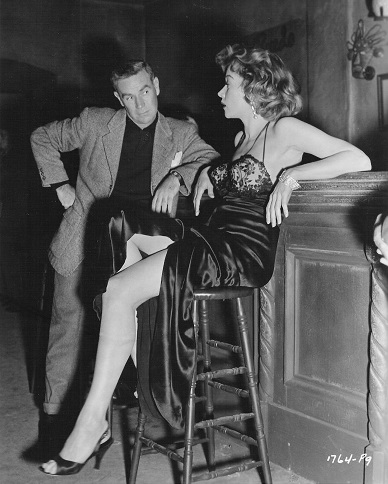

Who are we? Are we the sum of our experiences? Or a persona that can be discarded through accident or design but never entirely or without consequences? Natasha Kinski is the blonde, suffering from amnesia after she runs into the path of a car and is knocked over. The driver (played by Rubini) a young man from the rural South struggling to keep afloat in a Milan of dark elegance. A city where deep shadows seep from the classroom where he hunches over a desk learning the skills of a watchmaker, and out into the streets. La bionda needs help and crashes in his apartment. She gives him focus and a strange purpose through a hesitant yet compelling obligation. For a few short days they float in a maelstrom of doubt tempered by a softening dependency and growing intimacy. She searching for who she is, and he glimpsing what he could be. But reality intervenes, she remembers, and he is abandoned. He searches for her, finds her, but she is not the girl she was for those few short days. She is hard-bitten enough to know that he can’t be a part of that dark and sordid existence. He, oblivious, naively pursues a chimera of his own making, drawn on into a catastrophe with a brutally visceral and operatic climax.

Director Rubini is not passive. He takes his camera and literally spins it around scenes and events. Colors have a brightness and profundity that fuel both the emotional intensity of the protagonists, and telegraph the dangers that will entrap all the players in the end. Kinski when she returns to her erstwhile existence is embodied in red – lips, dress, and her car. Dark and vengeful destiny pursues her in black, and the hapless anti-hero stumbles along in white – ignoring Fate’s little hurdles that more than once give him a chance to escape.

Patience with an early slow pace more concerned with characterisation than narrative drive is amply rewarded in a dénouement of almost unbearable hysteria.