An hapless US munitions engineer visiting the Levant is the target of Gestapo spies

(1943 RKO. Directed by Norman Foster 79 mins restored version)

Unreleased preview version 91 mins

A Mercury Theater Production

Cinematography by Karl Struss

Screenplay by Joseph Cotten, Richard Collins, Ben Hecht and Orson Welles

Novel by Eric Ambler

Original Music by Roy Webb and Rex Dunn

Art Direction by Albert S. D’Agostino and Mark-Lee Kirk

Starring:

Joseph Cotten – Howard Graham

Dolores del Rio – Josette Martel

Orson Welles – Colonel Haki

Ruth Warrick – Mrs. Stephanie Graham

The official historical record has it that Orson Welles simply played a role in this movie, but original sources confirm that the film owes a lot to his creative genius. He had a part in writing the screenplay and in the direction. As Borde and Chaumeton say in their book A Panorama of Film Noir (1955):

“Journey into Fear, or ‘how fear makes people heroic’, bears the signature of Norman Foster, to be sure. But then Orson Welles collaborated on the scenario, and the exceptional breeziness and subtlety of his style emerge in the precision of the shooting script and the plastic beauty of the photography. Basing the film on a spy case that’s only a pretext and visibly turns into a hoax, Foster and Welles have rediscovered the chief laws of the noir genre: an oneiric plot; strange suspects; a silent killer in thick glasses, a genuine tub of lard buttoned up in a raincoat, who before each murder plays an old, scratched record on an antique phonograph; and the final bit of bravura, which takes place on the facade of the grand hotel of Batum. We may admire Orson Welles, with graying hair and mustache, in one of those minor, easy-going roles in which he excels: the Turkish Colonel Haki, head of the intelligence service and a womanizer.”

After mutilating The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) the year before, the studio bosses at RKO unsheathed their hatchets and hacked the completed Journey Into Fear from 91 minutes to 69 minutes for the US version and 71 minutes for the European release, and this was after various cuts from the screenplay required by the Breen office and The Legion of Decency. The 79 minute version currently available is a partial restoration, and the Welles.Net archive has a report of a further restoration. This report also provides some fascinating background on which scenes were cut.

The censors of the time, as from time immemorial, didn’t want audiences to have any fun, so as well cutting most political talk, they also had removed many scenes with ironic sexual references and any mention of religion. Still Journey Into Fear survives as a fascinating movie with moody atmospherics, exotic locales, sexy dames, weird villains, politics, wisdom, philosophy, and a wry humor.

A flawed gem, the picture is in a class of its own, and reminds me of John Huston’s glorious Beat The Devil (1953). Both movies have one guiding tenet: life is meant to be irreverent fun!

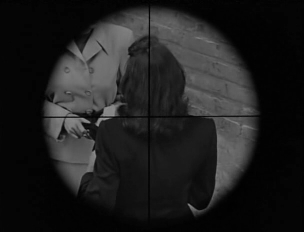

The beautiful opening shot before the credits that cranes up and peers into the window of a dingy hotel room at night and ends only after 80 seconds when the occupant leaves, and the magnificent climax on the outside ledges of another hotel at night during a rain-storm, are signature Welles. Welles has been quoted as saying that during filming, while the job of direction was given to Norman Foster, scenes were directed by “whoever was nearest the camera”. Bosley Crowther wrote in the NY Times on the film’s release: “that final duel in the beating rain on the ledge of a Batum hotel Mr. Foster [sic] has directed a melodramatic climax that is breathless and intense.”

Those familiar with the early novels of Englishman, Eric Ambler, will know that the on-screen person of Joseph Cotton is a perfect fit for the typical Ambler hero: a timid middle-class everyman who becomes unwittingly embroiled in a nefarious and dangerous caper where he discovers guile and courage he never thought himself capable of, and after his adventure, is happy to return to the succour of a comfortable obscurity. Welles himself has a rollicking good-time hamming it up as a womanising Turkish intelligence officer. Dolores Del Rio is wonderful as a cabaret singer with sexy exotic charm, loyalty, and a calm worldly-wise aplomb: she is the perfect foil to the shy and unromantic Cotten.

The art direction for the early cabaret scene where Cotton is made to realise he is the target of a hit-man is beautifully evocative, and the whole sequence is immensely entertaining. When the action quickly moves to a tramp steamer, the sense of claustrophobia is deftly handled. To quote Crowther again: “The fright of the ordnance expert is constantly underscored by an uncanny use of light and distorted shadows in the ratty corridors of the ship; in a blacked-out cabin one senses the terror of the hidden expert as footsteps echo from the pitch-dark screen”. Supporting roles that impinge on the protagonist have significant dialog and their characterisations are deeply drawn and well-acted. These characters also act as a philosophical chorus in scenes that while having a peripheral connection to the action, are anchored with elegant ruminations on god, war, love, death, politics, and marriage.

This is a connoisseur’s film: for those who rejoice in its eccentricities, wit, and romantic melodrama, while lamenting what has been lost to the barbarians.