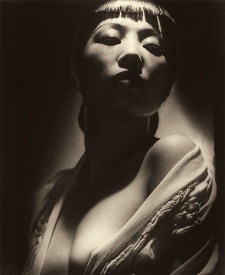

GEORGE HURRELL (American, 1904-1992):

Category: Lobby

Noir Poets: Bruce Springsteen

Atlantic City

Well, they blew up the chicken man in Philly last night

Now, they blew up his house, too

Down on the boardwalk they’re gettin’ ready for a fight

Gonna see what them racket boys can doNow, there’s trouble bustin’ in from outta state

And the DA can’t get no relief

Gonna be a rumble out on the promenade

And the gamblin’ commissioner’s hangin’ on by the skin of his teethWell now, everything dies, baby, that’s a fact

But maybe everything that dies someday comes back

Put your makeup on, fix your hair up pretty

And meet me tonight in Atlantic CityWell, I got a job and tried to put my money away

But I got debts that no honest man can pay

So I drew what I had from the Central Trust

And I bought us two tickets on that coast city busNow, baby, everything dies, honey, that’s a fact…

Now our luck may have died and our love may be cold

But with you forever I’ll stay

Were goin’ out where the sands turnin’ to gold

Put on your stockin’s baby, `cause the night’s getting cold

And maybe everything dies, baby, that’s a fact

But maybe everything that dies someday comes backNow, I been lookin’ for a job, but it’s hard to find

Down here it’s just winners and losers and don’t

Get caught on the wrong side of that line

Well, I’m tired of comin’ out on the losin’ end

So, honey, last night I met this guy and I’m gonna

Do a little favor for himWell, I guess everything dies, baby, that’s a fact…

– Bruce Springsteen (1982)

The Car in Noir: High Wall (1946)

The car in the film noir is a complex symbol expressing the various kinds of escape its protagonists attempt. It is also a tool of death… But as a symbol of the modern urban landscape, the car comes to mean much more: it functions as the symbol of all that has brought America to this ambiguous state of spiritual anxiety. Taunting us as the apex of industrial achievement with its commercial appeal and status, the car in the film noir has been transformed into an object of dubious distinction, like a desperado of sorts, an accomplice. Whether noir characters use it to escape their pursuers (legal or criminal) or their past, the automobile symbolizes that dangerous flight into the unknown that contrasts with its other importance as a symbol of established success in modern American culture. Desperate people steal perfectly reputable vehicles, transforming them into getaway cars, and in the act they sully the very status of material success that these object represent… In its transformation into an escape device, the car carries out one of the narrative goals of noir cinema: to bring the illusion of freedom for its characters up to its dead end—right up to the place from which they can no longer escape, and where they usually die.

– Andrew Dickos, STREET WITH NO NAME: A History of the Classic American Film Noir (The University Press of Kentucky, 2002), pp 176-177

High Wall (MGM 1946) is a film noir where cars are integral to the story and to the noir aesthetics: fast cars screeching to nowhere, dark streets, rain on asphalt, roadblocks, escape, entrapment… ‘crashing out’. Directer Curtis Bernhardt and his DP Paul Vogel in the many scenes with cars in this picture have fashioned indelibly mystic images of the noir car, as these selected frames from the movie attest:

Great Noir Posters: The Strange Woman (1946)

Noir Poets: W R Burnett

“And suddenly Roy didn’t give a damn about Velma, or about Pa and Ma. He realized that they had never been real people to him at all, but figments out of a dream of the past. He began vaguely to understand that ever since the prison gate clanged shut behind him he’d been trying to return to his boyhood, where it was always summer and in the evenings the lightning-bugs flashed under the big branches of the sycamore trees and he swung on the farm gate with the yellow-haired girl from across the road while the Victrola on the porch played Dardanella. . . . Pa and Ma were replicas of his own folks merely, and Velma wasn’t really Velma, a slim, ordinary little blonde, but the ghost of Roma Stover, the yellow-haired girl swinging on the gate. . . .”

W. R. Burnett – High Sierra (1940)

New York City Noir: The concrete jungle

“New York City. An architectural jungle where fabulous wealth…

and the deepest squalor live side by side.

New York, the busiest, the loneliest, the kindest and the cruelest of cities.”

– Voice-over after opening credits Side Street (1950)

Side Street (1950)

Director – Anthony Mann

DP – Joseph Ruttenberg

Story & Screenplay – Sydney Boehm

A tight and savvy noir exploring the claustrophobic canyons of New York ending with an ironically appropriate ‘crash’ on Wall Street.

Books Digest: Crossfire, Jewish Directors, and Streets With No Names – Part 2 Caught in the Crossfire

This is the second in a series of posts in which I discuss books on film noir that I have been reading, and which aficionados of film noir should find interesting.

In this post, I will look at CAUGHT IN THE CROSSFIRE: Adrian Scott and the Politics of Americanism in 1940s Hollywood (Columbia University Press, 2008) by academic historian Jennifer E. Langdon. The book can be purchased from Columbia University Press and the eBook is available free on-line at gutenberg.org

CAUGHT IN THE CROSSFIRE is ostensibly a biography of the activist writer and producer, Adiran Scott, who at RKO produced three seminal noirs of the 1940s directed by fellow progressive Edward Dmytryk: Murder, My Sweet (1944), Cornered (1945), and Crossfire (1947). Scott and Dmytryk were two of the HUAC Hollywood Ten. Historian Langdon devotes a number of chapters in the book on the production of Murder, My Sweet, Cornered, and Crossfire. The focus is on Crossfire and Scott’s adaptation with leftist writer John Paxton of the novel by Richard Brooks. Politics and the historical context aside, the chapters on Crossfire are a fascinating study of film production during the classic noir period. Andrew Feffer, Associate Professor, Director of American Studies, Union College New York, in a review of the book concluded that Langdon’s “detailed study of film production and politics is simply marvelous and well worth the read”.

What is most striking in Langdon’s lengthy account of the making of Crossfire is that it is a robust corrective to auteur theory. When film critics talk of Crossfire they see it as largely Dmytryk’s achievement. True, to the extent that he directed the picture we can give Dmytryk credit, but the screenplay is integral to the movie, and the very long and labored efforts of Scott and Paxton on that script must be acknowledged as deserving of equal if not greater recognition. Scott and Paxton were also closely involved in the shooting of the film, which was deliberately collaborative, as in the making of Murder, My Sweet and Cornered. Langdon relates an interest anecdote from the making of Murder, My Sweet (1944), as told by scenarist Paxton (my emphasis):

As a writer-friendly producer, Scott brought Paxton into the collaboration in ways that were not common within the highly segregated studio system. For example, he consistently invited Paxton onto the set, not only to have him on hand for possible rewrites, but simply to watch the filming. He also invited Paxton to watch the rushes and introduced him to the actors. Paxton recalled a minor stir when Scott introduced him to Dick Powell during the filming of Murder, My Sweet. “I will never forget the look of alarm and confusion on the face of the star when Adrian presented me as the Writer. He was a talented and friendly enough man, this actor, but I don’t believe he had ever met a writer before.” Paxton fondly recalled being invited along on trips to scout locations. “This was exhilarating, to be out with the fellows, crowded into the back seat of a stretch-out [limousine], suffocated by cigar smoke.” Paxton’s memories suggest a sort of boy’s-school camaraderie, and he clearly felt honored to be included in these masculine rituals, which were exalted by their intermingling of work and play. However, Scott dragged Paxton along to view rushes and scout locations not simply because he and Paxton were old friends and enjoyed spending time together. There was plenty of time to socialize outside of work, to play cards at each other’s homes or to have cocktails across the street at Lucey’s Restaurant, a popular gathering place for studio workers from RKO and Paramount. Scott included Paxton because he was trying to create a collaborative creative process, to break down the barriers enforced by the studio and to build a working unit. This creative—and political—agenda, this quest for a seamlessness between work and politics, reflected Scott’s larger political commitments and the spirit of the Popular Front. Paxton makes clear that Scott’s inclusion of him was unusual: “We [writers] had our place and we were expected to keep it. I might never have met a motion picture star if my friend, sponsor, and producer had not been Adrian Scott—a quite remarkable, and in his quiet way, a very radical man.”

Essential reading.

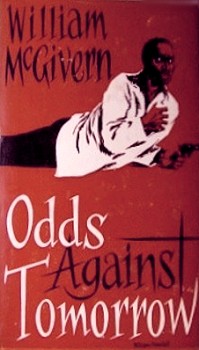

Noir Poets: William P. McGivern

Earl Slater – the white man:

Earl limped about pointlessly examining the junk on top of the mantel, studying the sturdy old beams and floor boards, pausing once to frown at the broken radio on the table. I’ll never see any of this again, he thought. Never see this room again in my life. Why should that bother him? he wondered. It was a cold, stinking dump. No man in his right mind would want to see it again. But leaving it reminded him of the other places he had left. He stood fingering the glass, while a dizzying succession of rooms and barracks and Army camps flashed through his mind. He was always the guy who had to leave, he thought. Everybody else stayed put, cozy and snug, while he hit the road. He never went back anywhere. There was no place on earth that called out to him, no stick or stone or blade of grass that belonged to him and nobody else.

Was it because he was dumb? Because he couldn’t feel what other people felt? The confident peace he had known after talking with Ingram had deserted him; he was uncertain again, worried and tense, afraid of the shadows in his mind.

Talking with Ingram he had licked this feeling. Or thought he had. Everybody was alone. Not just him, everybody. But what the hell did that mean? How did knowing that help you? he wondered.

Johnny Ingram – the black man:

A state trooper in a blue drill uniform was staring curiously at Ingram’s tear-filled eyes. “What have you got to cry about?” he said. “You’re not hurt.”

“Never mind,” a voice cut in quietly. Ingram recognized the voice of the big sheriff in Crossroads. “Let him alone.” The authority in the sheriff’s voice was unmistakable, but so was the understanding; the trooper turned away with a shrug, and Ingram wept in peace.

Later he was taken outside on a stretcher. The rain had stopped but a sprinkling of water from the trees mingled with the blood and tears on his face. Far above him he saw a single star shining in the sky. Everything was dark but the star, he thought. In his mind there was a darkness made up of pain and fear and loneliness, but through it all the memory of Earl blazed with a brilliant radiance. Without one you couldn’t have the other, he realized slowly. Without the darkness there wouldn’t be any stars. It was worth it then. Whatever it cost, it was worth it. . . .

Deadline at Dawn (1946): Screwball noir

An Adrian Scott production for RKO, Deadline at Dawn (1946) is a great ‘screwball’ noir that is a must-see. A young Susan Hayward is as cute as a button in the lead role of a taxi-dancer who falls for a sailor mixed up in the murder of a b-girl. The screenplay by Clifford Odets is based on a Cornell Woolrich story, and is as dark as any noir and as left as a Hollywood movie could go at the time. At the end, a guy who has murdered a female blackmailer and general no-good dame, as the cops lead him away, laments “Imagine, at my age, to have to learn to play a harp”. Think about it. Subversive yes! It is the only feature directed by Broadway director Harold Clurman, who was moon-lighting in Hollywood at the time, after the break-up of the Group Theater in NY. DP Nick Musuraca’s chiaroscuro lensing completes the picture. As Trevor Johnston says in his review for the Time out Film Guide, “it’s made with cockeyed artistry from beginning to end, and shouldn’t be missed”.

The action takes place in a single night in New York, with a signature Woolrich race against time. Much of Odets’s dialogue owes little to Woolrich and is an entertaining mash-up of clever puns that is in the tradition of the romantic screwball comedies of the period. A cavalcade of character actors portrays an ensemble of zany denizens of the New York night; taxi-dancers, b-girls, gangsters, blackmailers, besotted drunks, and cabbies. But there is a serious underside: the greed, corruption, and passions of the noir city, where a murder seems the only way-out, and where trusting a stranger is seen as foolish even if the guy is in a jam.

There is a lot of left philosophising, as you would expect from an activist team of film-makers. Academic’s have taken issue with this alleged hijacking of Woolrich’s story. Mayer and McDonnell in Encyclopedia of Film Noir (2007) complain that “Unfortunately, the film’s script tries to inject overt social meaning, and Woolrich’s clever plot is pushed aside by Odets’s pretentious dialogue”, and Robert Porfiro in Silver’s and Ward’s Film Noir: A Encyclopedic Reference (1992) concludes “Odet’s patronizing concern for the common people, and even worse, his pseudo-poetic, elliptical dialogue are out of place in the lower-class locales of the film”.

Porfirio’s political prejudices aside, these haughty criticisms of Odet’s dialogue don’t align with my feelings. Odet’s dialogue is clever and rings true for every character. The sailor is a small-town boy with solid values and his simple home-spun philosophy of honesty and fairness is totally believable. Hayward’s taxi-dancer is also from a small town and the necessary cynicism she has acquired in the dark city is genuine – a matter of survival – but she retains her formative values and acts on them despite her city ways. She is attracted to the young ‘hick’ sailor because he unlike most guys in the big city does not have an angle: what you see is what you get. Here Odet’s focus is the fundamental noir motif of city vs. country, corruption and immorality vs. sincerity and decency.

A taxi-driver who helps the couple, Gus Hoffman, is played with assurance by Paul Lukas. Gus, an immigrant with a strong accent, is the film’s philosopher and the target of Porfiro’s attack. He is a man who has seen injustice and suffering, and his words are world-weary and wise. Such men exist and I have known many: working people educated in the school of life.

You make your own judgment. This is a conversation between Gus and the Susan Hayward character, June, before they are interrupted by a cop on the beat:

Life in this crazy city unnerves me too,

but I pretend it doesn’t.

Where’s the logic to it?

Where’s the logic?The storm clouds have passed us.

Over Jersey now.

Statistics tell us we’ll see the stars again.Golly, the misery that walks around

in this pretty, quiet night.June.

The logic you’re looking for…

…the logic is that there is no logic.

The horror and terror you feel, my dear,

comes from being alive.

Die and there is no trouble,

live and you struggle.

At your age, I think it’s beautiful

to struggle for the human possibilities…

…not to say I hate the sun

because it don’t light my cigarette.

You’re so young, June, you’re a baby.

Love’s waiting outside

any door you open.

Some people say,

“Love is a superstition.”

Dismiss those people,

those Miss Bartellis, from your mind.

They put poison-bottle labels

on the sweetest facts of life.

You are 23, June.

Believe in love and its possibilities

the way I do at 53.What’s wrong here?

This man bothering you?He’s the only man in four years

in New York who hasn’t?

Noir Poets: Ira Wolfert

All the things a man has to go through to get to live here, thought Leo, the things, the things, thousands and millions and millions of dirty things to hurt people and hurt himself. The street seemed drowned in stone. It looked narrow and drowned, a thing emptied of life and walled with swollen, stone bones. The feeling of costly desolation was heavy in Leo. This costly desolation was splendor, but Leo did not think of it as splendid. Yet he tried to be faithful to the rich. He tried to think of the costly desolation as good for sleep. Only the rich could afford to buy quiet like this in the heart of the city, he told himself. He felt suddenly that only a man who had made himself rich could become barren enough to want and be comfortable in this desolation.

– Ira Wolfert, ‘Tucker’s People’ (aka ‘The Underworld’), NY, 1943, p. 71

Abraham Polonsky’s and Ira Wolfert’s screenplay for Force of Evil (1948) was based on Wolfert’s novel.