Marcel Carne’s Hotel Du Nord is seen as part of a trilogy that encompasses two other of his films from the 1930s: Le quai des brumes (Port of Shadows 1938) and Le jour se lève (Daybreak 1939). These films represent what has been termed ‘poetic realism’, a gritty fatalistic French cycle of films seen as a precursor of the classic film noir cycle, with a male protagonist failing dismally to escape a dark past with a doomed romantic entanglement. Unlike the other two movies, Hotel du Nord is not based on a script from Carne’s famed collaborator, Jacques Prévert, but by scenarist Jean Aurenche, which some critics see as a weakness. The film has on the surface a lighter touch, and much of the dialog crackles with simple humanity, jokes and good-natured innuendo. But there are deeper layers of meaning, and these come from the screenplay.

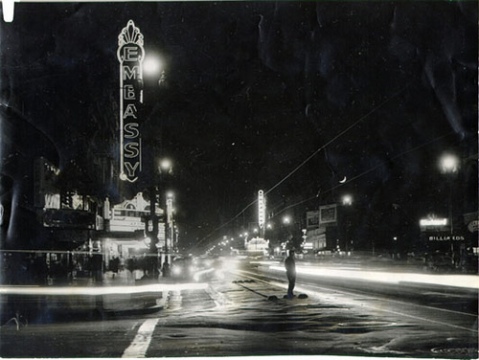

The scenario revolves around the daily dramas of a not-so-grande hotel in downtown Paris. Amongst others, of principal interest for me are the indomitable Arletty as a b-girl shacked up with a hood, played by Louis Jouvet with world-weary elegance, who is in hiding after ratting on an accomplice. The story revolves around a botched suicide pact between a pair of young lovers, and the dénouement is driven by the arrival of Jouvet’s framed accomplice out for revenge. The whole affair plays out in front of the real Hotel du Nord and in a magnificent studio lot, complete with a canal, bridges, trams, village shops, and the Hotel, conceived by art director, Alexandre Trauner, who also worked on Carne’s masterpiece, Les enfant du Paradis (1945). Maurice Jaubert’s deeply romantic and evocative score completes the scene.

Aurenche’s script and Carne’s mis-en-scene develop a duality: the generosity and humanity of daily life versus the dark flip-side of angst, cowardice, and cruelty. Goodness nurtures healing and reconciliation, while falsity and lies breed suffering and terrible revenge. When the hood Jouvet declares his love for a young woman and failed-suicide, Renée, he proposes as ‘Robert’, the man he was before he became a criminal and who then took on another bi-polar identity to hide from his pursuer – love demands purity of intent and the grace he desperately seeks to recover – fate however, has other ideas. Jouvert as the squealer ‘Paulo’ was a shy bumbling petty-crook scared of blood, and now in hiding as ‘Monsieur Edmond’ he is a severe dandy who kills chickens for local housewives by strangling them with his bare hands. Arletty’s whore Raymonde is engaging, tolerant, and sharp, with a seeming heart of gold. But her final revenge as spurned lover is a dark act of treachery.

Raymonde survives without regrets between the sheets of a more compliant lover, Robert’s ultimate self-abnegation is absurd rather than tragic, and the final reconciliation of the young lovers in the closing scene is more fantasy than real. As dark as any noir.