Regular readers of FilmsNoir.Net will know of my focus on the redemptive element of film noir, and my recent concern with the nihilism in most contemporary post-noir Hollywood films.

In my recent post In the Valley of Elah (2007): Responsibility and Chaos I talk about my conception of the noir sensibility, which “must have a redemptive focus for me to value a film, whether redemption is achieved or not. This is what the great films noir have in common: a profoundly and deeply human response to the chaos and random contingency at the edge of existence”, and in the post Post-Noir: The New Hollow Men, I express the view that “too many film pundits today are happy to spout the received wisdom that film noir was a response to some pervasive (but in reality non-existent) post-WW2 trauma-cum-malaise, and then uncritically enlist this (thoroughly) conventional wisdom as some contrived justification for the plunge of contemporary American cinema into an abyss of banal fascist violence: most recently American Gangster, Death Proof, Gone Baby Gone, Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, and No Country for Old Men“.

This is by way of introduction to a most unlikely new book on film noir: Arts of Darkness: American Noir and the Quest for Redemption by Thomas S. Hibbs, a Baylor University professor of ethics and culture and film critic for the conservative National Review Online.

by Thomas S. Hibbs, a Baylor University professor of ethics and culture and film critic for the conservative National Review Online.

I have not read the book, and I certainly don’t share the politics of the author, his reading of history, or his religious affiliations, but from what I have read about the work, it offers a novel perspective on film noir, which resonates with ideas I have previously put forward about redemption versus nihilism, though my conception of redemption has a humanist if not spiritual stamp.

In a post today on the book, Light In the Shadows, Chuck Colson from Breakpoint, a US Christian community concerned with prisoner outreach, outlines Hibbs’ thesis:

Hibbs borrows Pascal’s concept of a “hidden God” to help show the motive that drives many of the characters in film noir. Films like Double Indemnity and Maltese Falcon, Hibbs explains, show a reaction against the kind of shallow, facile optimism born out of the Enlightenment period—a mentality that taught that all things were possible through rational thinking and scientific observation. Film noir, by contrast, is all about the restraints on humans in a sinful world. It tells us that we cannot just do anything we feel like doing with impunity.

As Hibbs writes, “In its assumption that a double”—that is, “a dark self”—“lurks just beneath the surface of the most ordinary individuals, noir punctures naïve, conventional assumptions about human behavior. But the dark side is [not] liberating. . . . The characters who try to exercise a Nietzschean ‘will to power,’ to exist beyond good and evil, destroy themselves instead of triumphing.”

Before proceeding further, I must repudiate the dismissal of the Enlightenment: this is just plain wrong. No-one can accuse the father of the Enlightenment, Voltaire, of “facile optimism”. Having said this, Hibbs’ has something very interesting to say.

An excerpt from a review in National Review February 25 2008:

Hibbs writes that, although noir seems bleak and cynical on the surface, the meaning behind the phenomenon is a good deal more complex and significantly more positive: What is significant about these films is not just that they present a dark and dismal world but that they display their main characters as on a quest for love, truth, justice, and even redemption. What interests Hibbs is the convergence of noir with the religious quest : Noir arises from the same impulses that prompted Pascal to write of the hiddenness of God, and of the faithful believer who seeks with groans.

Hibbs sees noir as engaging and critiquing the two major philosophical dangers of modernity: nihilism and Gnosticism. He writes: Enlightenment theorists promise liberation from various types of external authority: familial, religious, and political. But an unintended consequence of the implementation of Enlightenment theories is the elimination of freedom. The film noir vividly expresses this truth, as the protagonists find themselves ever more deeply enmeshed in the complex, bureaucratized, soulless modern cities and webs of uncaring institutions that are the consequence of the Enlightenment passion for controlling the world through science. In portraying the tragic limitations of the Enlightenment project, Hibbs argues, noir shows liberal modernity as a potential source of nihilism, a human existence devoid of any ultimate purpose or fundamental meaning, where the great tasks of inquiry and the animating quests that inspired humanity in previous ages cease to register in the human soul, a place where the very notion of a soul is suspect.

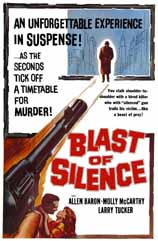

, a little known low-budget independent production from Allen Baron made in 1961:

The wrong guy is convicted of a murder…

The wrong guy is convicted of a murder…