City Streets (1931) Speakeasy delivery convoy…

Director – Rouben Mamoulian | Cinematography – Lee Garmes

FilmsNoir.Net – all about film noir

the art of #filmnoir @filmsnoir.net | Copyright © Anthony D'Ambra 2007-2025

City Streets (1931) Speakeasy delivery convoy…

Director – Rouben Mamoulian | Cinematography – Lee Garmes

“film noir is like a Harley-Davidson: you know right away what it is… the object being only the synecdoche of a continent, a history and a civilization…”

“As it has come down to us through the decades, it is an object of beauty, one of the last remaining to us in this domain, situated as it is between neo-realism and the New Wave, after which rounded objects like these will no longer be made… because there is always an unknown film to be added to the list, because the stories it tells are both shocking and sentimental… film noir is like a Harley-Davidson: you know right away what it is. The object being only the synecdoche of a continent, a history and a civilization…”

– Vernet, Marc (1993). “Film Noir on the Edge of Doom”, in Copjec, Joan, ed. (1993). Shades of Noir. London and New York: Verso. ISBN 0-86091-625-1, pp. 1–31.

This edited quote is from the opening paragraph of the cited article by French film academic Marc Vernet. The full paragraph is set out below.

Vernet here is cheekily setting up the reader. We nod yes, and yes, as we read through this metaphysical paean to film noir, but Vernet’s purpose is to demolish this mythic edifice. Vernet sees the conception of film noir as a deluded idée fixe conceived by the French film writers of the immediate post-WW2 from a corpus of films released in a flood of American movies screened in liberated Paris in 1946.

In essence Vernet considers film noir an invalid construct. For Vernet, what noir aficiniados see as films noir are simply crime movies; chiaroscuro filming was evident in Hollywood movies since 1910; and German expressionism is hardly an influence. I can buy this up to a point. I have always thought that Expression has only a tenuous connection with film noir, and Vernet argues the chiaroscuro angle strongly by reference to a number of pre-code Hollywood films – talkies and silents. But his justification of the view that film noir is an idée fixe is scoped so narrowly as to negate his own argument. He insists that the noir canon comprises only crime stories featuring a private detective and a femme-fatale, and he has nothing to say about French poetic realism.

I do though like Vernet’s explanation of why post-war French film scholars and the enfants terribles of the New Wave so loved film noir. I don’t fully agree with how get’s there though. He sees film noir – as he narrowly defines it – as ‘conservative’: the hard-boiled hero is a defender of traditional values against the conglomerate; as the individual against the collective – a sort of proto-superman – like Gary Cooper’s architect in King Vidor’s expressionist bizarro noir of Ayn Rand’s unreadable novel ‘The Fountainhead’. For me the idea that film noir is not subversive does not stand up to any fair analysis. I have dealt with this issue at length in many articles posted at filmsnoir.net, and will leave it to the reader to explore those arguments more fully in those posts.

Getting back to why Vernet thinks the French noiristas of the 40s and 50s loved noir. Those leftist intellectuals – the likes of Godard, Truffaut, Claire, and Rivette, according to Vernet had to sublimate their hatred of American imperialism to their love of Hollywood movies, particularly films noir and b-movies, by seeing in those pictures a critique of capitalism and its alienating institutions. To my mind he reaches a pretty fascinating conclusion albeit for the wrong reasons. Classic film noir is subversive and many of the classic noirs were critiques of traditional values, and were made by committed leftists and others not comfortable with the ethos of American capitalism.

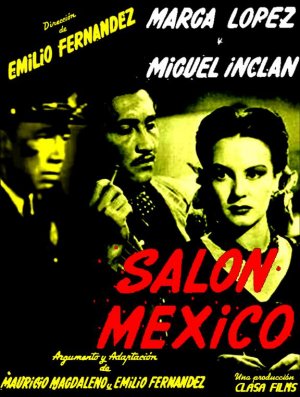

A beguiling Latin melodrama, Salón México stars Marga López as a b-girl at the Salon Mexico cabaret in Mexico City where she “sells her services” …

Director: Emilio Fernández

Writers: Emilio Fernández (story), Mauricio Magdaleno (story)

Cinematography: Gabriel Figueroa

Starring: Marga López, Miguel Inclán, and Rodolfo Acosta

A beguiling Latin melodrama, Salón México stars Marga López as a b-girl at the Salon Mexico cabaret in Mexico City where she “sells her services” to put her younger sister through an exclusive boarding school. An infernal triangle with a violent home-fatale and a sympathetic cop threatens to thwart her selfless sacrifice and destroy the dreams she holds for her sister’s future.

Mercedes is a mulatta, and social realism is infused with a strong religiosity and patriotism, but the drama drives the narrative, and the noir motifs of entrapment and fatalism are well to the fore. So we can forgive a dewy-eyed epilogue to the tragic denouement. The movie is interesting also for folkloric interludes and its eroticism, which in an early scene at the Salon Mexico is for the period quite daring.

López is enchanting as Mercedes and well served by a strong supporting cast. Director Fernández and cinematographer Figueroa use deep focus and on-the-streets filming to deliver a fascinating vérité feel to proceedings, and they enrich our enjoyment with chiaroscuro scenes of real panache. Available lighting is used to excellent dramatic effect.

In 1950 López was awarded the Mexican Silver Ariel for Best Actress for her portrayal. Salón México was screened at Cannes in 2005 as part of the Classic Cinema segment along with two other films by Fernández. The movie will screen at the 9th Morelia International Film Festival in October.

Thirty years ago in my late 20s on many lonely cold winter nights I walked the desolate streets of the city fringe… down narrow sparsely-lit alleys

Thirty years ago in my late 20s on many lonely cold winter nights I walked the desolate streets of the city fringe. Down narrow sparsely-lit alleys with dark dirty store-fronts, ominous warehouses, and desperate characters. A salty dampness and the silhouettes of sea-faring hulks on Sydney harbor drawing me into an enveloping angst. There was mystery, an aching feeling of some unfathomable loss, of poetry.

Today those streets are bright, lined with trendy restaurants, exclusive warehouse conversions, soul-less showrooms for funky furniture, and expensive cars. No mystery, no angst, and no poetry.

The people behind the Noir Nation project have produced two excellent promotional videos which augur well for the quality of the publication…

I came across the Noir Nation project on KicketStarter.com this evening. The people behind the project are seeking pledges for a new eJournal of crime fiction offering high quality prose fiction, non-fiction, graphic novels, and visual arts.

The people behind the project have produced two excellent promotional videos which augur well for the quality of the publication. But their funding deadline of July 6 looms and pledges are nowhere near the target of US$10,000. Any venture capitalists with big bucks should check out the site.

The Warner Archive has released on DVD for the first time a film adaptation of the Ernest Hemingway novel, The Breaking Point (1950)

The Warner Archive has released on DVD for the first time a film adaptation of the Ernest Hemingway novel, The Breaking Point (1950), a great John Garfield noir directed by Michael Curtiz, and to my mind infinitely superior to Howard Kawk’s over-rated adaptation To Have and Have Not (1944).

Salón México (1949) Nylons, high heels, and dark alleys… Director – Emilio Fernández | Cinematography – Gabriel Figueroa

Salón México (1949)

Nylons, high heels, and dark alleys…

Director – Emilio Fernández | Cinematography – Gabriel Figueroa

Most film noir protagonists are driven by anger. Anger grown of frustration and resentment at a society that excludes them from comfort and a decent life…

Most film noir protagonists are driven by anger. Anger grown of frustration and resentment at a society that excludes them from comfort and a decent life. Some are simply lazy and greedy and see crime as a fast lane to riches, many are driven by poverty and degradation to crime, also as a kind of revenge against ‘those’ who have taken everything and left nothing, and all share the widely held delusion that money buys happiness.

In the female prison noir, Caged (1950), a powerful critique of a society that breeds such anger, a young woman is jailed after she is an unwitting accomplice in a gas-station robbery with her husband, who is killed during the heist. The sheltered girl on admittance to a women’s prison discovers she is pregnant, but her condition does not protect her from the humiliation and brutalisation of prison life. Melodramatic but with a strong social conscience that targets corrupt authorities, the movie is downbeat and pessimistic. By the end of the film, the girl is hard-bitten beyond her years and ready to hit the streets as a prostitute, after her recruitment by a glamorous older inmate, who manages to run her racket from inside the prison. The prison warden tries hard to help such girls but money is in short supply and the politicians aren’t interested. The girl’s decision to go bad is triggered by the resentment that erupts when from her cell she is confronted with the site of a gaggle of socialites dressed to the nines in a philanthropic tour of the prison. We appreciate her anger and resentment as an understandable response to her treatment by ‘the system’.

Hollywood doesn’t make movies likes that anymore thanks to the HUAC purges of the 1950s and the comfortable cowardice of contemporary film-makers.

I get angry at injustice and inequality, very angry. What intrigues me is why Americans don’t get angry at the injustice and inequality in their midst. For the record I am not American nor do I live in America, and for many Americans that disqualifies me from having a view, but I don’t care. If you personally have a problem with this, write to your member of Congress.

A sobering article was published today by my local newspaper.

Get angry America!

Office memorandum, Walter Neff to Barton Keyes, Claims Manager. Los Angeles, July 16th, 1938. Dear Keyes: I suppose you’ll call this a confession when you hear it. I don’t like the word confession…

Office memorandum, Walter Neff to Barton Keyes, Claims Manager. Los Angeles, July 16th, 1938. Dear Keyes: I suppose you’ll call this a confession when you hear it. I don’t like the word confession… When it came to picking the killer, you picked the wrong guy, if you know what I mean. Want to know who killed Dietrichson? Hold tight to that cheap cigar of yours, Keyes. I killed Dietrichson. Me, Walter Neff, insurance agent, 35 years old, unmarried, no visible scars – until a little while ago, that is. Yes, I killed him. I killed him for money – and a woman – and I didn’t get the money and I didn’t get the woman. Pretty, isn’t it?

I am currently reading a book on French cinema by American academic T. Jefferson Kline titled Unravelling French Cinema (John Wiley & Sons 2010). As the title indicates, Kline by examining French films from the early 1930s to the present day explores the nature of French cinema. His guiding thesis is that French films are more concerned with the nature of cinema than with narrative for its own sake. It is a complex analysis and the author’s scholarly approach makes the book daunting reading.

Kline initiates an intriguing discussion of cinema as a process of mourning, which goes not only to the examination of certain films but to the very nature of cinema. He focuses on art-house films and strangely mentions French poetic realism only as an aside. The great poetic realist films of the 1930s are not discussed, nor the French noirs of the 1940s and 1950s. The fatalism of these films to me seems germane to any discussion of cinema as mourning, and to an understanding of film noir.

Let us take these word’s from Kline’s book: “We can think of many films that move us precisely because the main character must die, and so we mourn… we must realize that cinema in its most essential form is an image of something that is no longer there. Like a cherished photograph, we can look at it over and over again, but we can never make its subjects return to the physical form they enjoyed when the film was made.” (p. 334)

This is the very nature of the fatalism inherent in poetic realism and in film noir: a doomed protagonist battling the fates. The very use of flashback in many noirs reinforces this fatalism – the fate of the protagonist is known from the outset. Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944) and Robert Siodmak’s The Killers (1946) are the definitive flashback noirs.

Something to think about.

He Ran All the Way, John Garfield’s last picture, was made under the oppressive shadow of HUAC. Soon after its release Garfield was dead from heart failure.

He Ran All the Way, John Garfield’s last picture, was made under the oppressive shadow of HUAC. Soon after its release Garfield was dead from heart failure. Dalton Trumbo wrote the script (under an alias), John Berry directed, James Wong Howe lensed, and Franz Waxman penned a dramatic score. This team, along with a strong supporting cast deliver a solid picture. It has flaws – a tendency to melodrama and plot contrivances – but it delivers a strong noir punch.

Garfield is a nervous small-time loser who kills a cop during a payroll heist and holes up an innocent family in their apartment as he desperately seeks to evade capture. The guy is screwed-up big-time but underneath it all has some desire for connectedness. He is brutal but gentle, ruthless yet hesitant, hateful while desperate for love. Garfield’s portrayal is pitch-perfect and a worthy epitaph. Shelley Winters in an early role as a young innocent does really well in a difficult role.

Strange that I have yet to read a serious review of the film. NoirofTheWeek.com provides a signature belabored outline of the plot and little else. Bosley Crowther in the NY Times on the movie’s release couldn’t see the forest for the trees in a petulant dismissal resting on alleged weak characterisations. Glen Kenny on TheAutuers.com treats the film as an opportunity for self-satisfied satire.

Those bloodhounds at HUAC would have had you believe this scene from the picture is ‘commie’ propaganda:

Sunday morning in the hostage family’s kitchen. Garfield is drinking coffee while the father (Wallace Ford) works on a model boat. Garfield has just turned off the radio after a church sermon is announced.

JG: What that church stuff do for ya anyway, what’s it get ya?

WF: Well… for one thing it makes a man understand the nature of love.

JG : Yeah?

WF: Yeah… The faith that there’s someone more important than yourself, that your family’s more important than both of you, and that every other human’s a member of your family…

JG: What’s a holy joe like you get outta life? What ya want outta life?

WF: To be left alone, to work, to be left alone.

To be left alone. But life won’t leave us alone. This is what noir is all about.