In 1949 British director Carol Reed and Australian born cinematographer Robert Krasker made The Third Man. One of the great films of the 1940s and a signal film noir. Two years earlier the pair worked together on Odd Man Out. While Odd Man Out is less widely known, the film is of sufficient stature to rank as an essential film noir.

In Odd Man Out Reed and Krasker reveal the nocturnal soul of the regional city of Belfast, a port and industrial town in Northern Ireland, as they did to greater acclaim the more urbane environs of post-war Vienna in The Third Man. A dark fatalism imbues both films, which are concerned with a police hunt for a criminal. Each protagonist is drawn with a certain ambivalence, and both men are loved by a woman who sees past their crimes. These scenarios have an engaging cavalcade of characters as in a true human comedy, yet it is the antagonism of love and friendship on the one hand, and the imperatives of conscience on the other, that matter. In The Third Man, the dilemma is whether loyalty out of passion is stronger and more genuine than the loyalty of friendship, where the object of affection is without scruples and commits despicable acts. Harry Lime is an engaging rogue but his crimes are immoral and motivated by greed. Odd Man Out however presents us with a protagonist whose morality is more problematic.

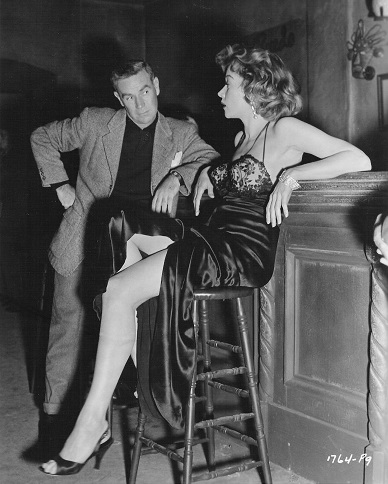

In the opening scenes of Odd Man Out the leader of an IRA cell played by James Mason is shot and wounded during a heist to raise cash, and in the struggle to escape, he shoots and kills a cashier. The rest of the story follows his desperate attempts to reach a safe house where the young woman who loves him is waiting. He engages in not only this physical struggle but also with an agonising remorse at having taken a life. Here the film meanders a bit while a clutch of humanity is caught up in the pursuit. Betrayal, avarice, and spirituality are all given a place, but it is altogether too much like preaching, and some odd humour jars even though it is a barbed portrayal of greed and artistic pretensions. The poetry here is in the dark yet glistening visuals as we follow Mason on his path through the city at night and in the rain.

The inevitable dénouement has a tragic pathos that echoes not so much film noir but more the fatalism of French poetic realism. If we are charitable the ending is a homage to Julien Duvivier’s Pépé le Moko (1937), and if we are not so inclined it harkens unmistakably to the motifs and mise-en-scène of that film.

Mason beautifully inhabits his role in a strong physical sense where his words are few and often soliloquies. As the girl who loves him, Kathleen Ryan is a commanding presence – her quiet stoicism masks a deep passion and devotion. A woman straight from a novel by Simone de Beauvoir. Her actions sharply mark her as an existential hero, so much so that the closing scenes achieve a different resonance than in Pépé le Moko.

One of the great films noir and, to quote Peter Bradshaw from the UK Guardian, “an eccentric masterpiece”.