A young woman who is a kleptomaniac and a pathological

liar wreaks havoc in the lives of three men

(1946 RKO. Direction by John Brahm 85 mins)

Cinematography by Nicholas Musuraca

Screenplay by Norma Barzman (uncredited) and Sheridan Gibney

Original Music by Roy Webb

Art Direction by Albert S. D’Agostino and Alfred Herman

Starring:

Laraine Day – Nancy Monks Blair Patton

Brian Aherne – Dr. Harry Blair

Robert Mitchum – Norman Clyde

Gene Raymond – John Willis

“Never has the device of the flashback been taken so far. Narratives are jumbled up, parentheses opened, exploits slot one inside the other like those Chinese toys sold in bazaars, and the figure of the heroine gradually comes into focus: beneath her somewhat obscure charm there lurks a dangerous and perverse mythomaniac”

– Borde & Chaumeton, A Panorama of American Film Noir 1941-1953 (1955)

“The Locket is a radically ambivalent film… [it’s] oscillation between condemnation and sympathy for its central protagonist, draws attention to the processes of narration and to the attempt of male narrators to control the ‘problem’ of femininity.”

– Andrew Spicer, Film Noir (2002)

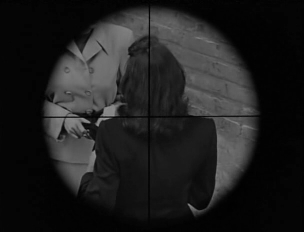

The Locket is a bizarre melodrama that marks one the first films noir to use Freudian concepts to explore criminal psychology. Though the film is studio bound, the film-makers have used this constraint to advantage. Under the assured direction of John Brahm [who also directed The Brasher Doubloon (1947), Hangover Square (1945), and The Lodger (1944)], cinematographer Musuruca, and art directors Albert S. D’Agostino and Alfred Herman, place the story firmly in a suffocatingly surreal mise-en-scene. The atmosphere is decidedly gloomy – even baroque – with many dramatic scenes so darkly lit that there is aura of grim foreboding that goes far beyond the immediate action.

Larain Day, a little known b-actress, is entirely convincing as Nancy, the woman who weaves an elaborate charade only a disturbed mind could navigate, handling the melodramatic climax with considerable style.

The first thing that takes your breath away is what Borde & Chaumeton describe as a “technical shot in the dark”: the audacious use of flashback. There are two male narrators and finally Nancy herself, who each in turn construct a flashback within a flashback within a flashback. The final flashback takes Nany back to her childhood where her widowed mother works as a servant in the mansion of a haughty rich woman. The scenario in this flashback intelligently establishes the root cause of Nancy’s psychosis, while her treatment as a child of ‘the help’ initiates in the viewer sympathy for the character as a child, and an ambivalent empathy for the troubled woman she becomes.

A music box and its tune is a strong motif in the film, and in the climactic ending, this musical motif triggers a psychotic episode that is both cathartic and catastrophic. These scenes depicting Nancy’s disintegrating mental and physical state are inventively portrayed by innovative camera-work and by Roy Webb’s musical acumen.

The theme of entrapment is multi-layered. While Nancy is a prisoner of her compulsion and childhood trauma, each of the men who love her is equally attracted and repelled by the enigma that lies beneath her longed for persona. One of the men, an artist played by Robert Mitchum, expresses this exasperation in a portrait of Nancy in which her eyes are incomplete.

A must-see noir.