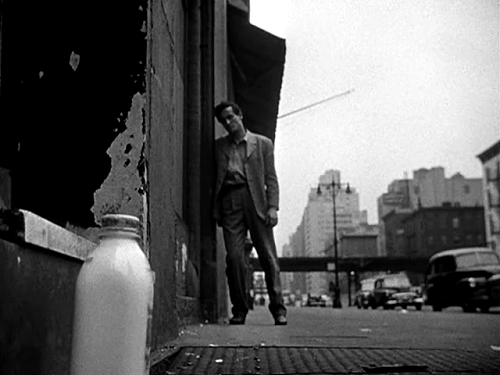

Tony Curtis’ best role has to be the sleazy publicist Sidney Falco in Alexander Mackendrick’s acid noir Sweet Smell of Success (1957). Burt Lancaster’s manipulative NY celebrity columnist enlists the amoral Falco to destroy his younger sister’s suitor. These guys are as bracing as vinegar and cold as ice: ambition stripped of all pretense. The chemistry between Lancaster as the sinister chat columnist and Tony Curtis as the ruthless publicist is palpable. It is also DP James Wong Howe’s sharpest picture – the streets of Manhattan have never looked so real.

Category: Lobby

The Noir Vignette: “Don’t forget – your dead father was a ‘lousy foreigner’”

In The Glass Wall (1953), the protagonist is an Hungarian war refugee, Peter Kaban (Vittoria Gassman), who jumps ship after his quest for entry into the US is rejected. A stowaway and without sufficient evidence of his assisting the US war effort by helping a wounded GI, the young man’s deportation is imminent. Kaban’s only chance is to find the GI. All he knows about the vet is that his name is Tom, that he is from New York, that he plays the plays the clarinet, and that he talked about the wonder of a place called ‘Times Square’. Kaban’s search has him roaming the teeming streets of Manhattan and visiting venues with jazz bands playing. These scenes of Kaban amongst the crowds on the streets of NY are documentary, and the central noir motif of individual alienation in the anonymity of the city is dramatically evoked – a cold glass ‘wall’.

But in his jump from the ship Kaban has injured a rib and his search for Tom becomes more desperate as his injury progressively weakens him. After getting help from Maggie (Gloria Grahame), a young woman on the skids, they are separated after he escapes arrest on a crowded subway platform. By now his photo is plastered on the front page of the evening papers.

Back on the streets he hears jazz from a burlesque dive and enters from back-stage. A show is in progress with a stripper on stage. Kaban is visible at the curtain as he peers at the clarinetist – no luck. His appearance attracts the attention of the rowdy patrons, and the stripper is not amused. She yells to the stage manager: “Throw that bum out. He’s lousing up my act.” Kaban is pitched out the back of the theater and stumbles into the back-seat of an empty cab at a taxi rank.

The scenario is now set for the vignette, which in terms of the plot, has only a single purpose: to inform Kaban of the existence of the UN and its humanitarian charter, and that it is in NY, the ‘glass wall’ of the title. However, the scenario evocatively reinforces the film’s central theme of personal obligation and social responsibility, with such a deep humanity and charm that it leaves an indelible imprint on your memory. The dialog and the acting are pitch perfect.

The stripper Bella Zakoyla, who goes under the stage-name of Tanya, is played by bit player Robin Raymond. Her performance is really impressive. She is not young, on the cusp of middle-age, and when we first see her on stage, she fills the frame, and the sincerity of her ‘act’ is striking. She has a joyous grace. When she finishes work she enters the same cab still parked back-stage and hails the driver from a news-stand. The cab heads for her apartment and she discovers Kaban asleep next to her. She recognizes him from his photo in an early edition on the front page of the day’s newspaper. She has spunk and jokes with the cab-driver after asking him to detour to a police station on the way to her apartment. At the precint station, she leaves Kaban asleep in the cab and enters the station. After a while she returns. We have been played by a neat little conceit in the script: she wanted to check if the guy was on the level before taking him home! By this time, Tom the clarinetist, who also saw Kaban’s photo in the newspaper, has confirmed his story with the authorities, and now they only want to locate Kaban to tell him and process him as displaced person.

The cab arrives at Tanya’s tenement building, where as a single mother she supports her own widowed mother, an Hungarian immigrant, her two young children, and a brother, who is not in regular employment – he is a huckster for poker sharps. She puts Kaban in the bed she shares with her two kids while she waits for her mother to serve the supper she has prepared. The old lady is suspicious of Kaban at first, but is persuaded that he is kosher and needs their help. Then the brother turns up flush with dough he has ‘earned’ that night. It is clear that this boy is a disappointment after being put through school by Tanya. He blows up when he finds out Tanya is harboring Kaban, and threatens to throw him out. We cut to Kaban anxiously overhearing the argument in the closed bedroom with the kids, who are now awake, intrigued and smiling. He hears about how Tanya intends to go to the UN in the morning. Back in the living room, the argument continues, and ends only after Tanya’s mother slaps her son across the face for a racist outcry.

Tanya goes to the bedroom to rouse Kaban for supper, and finds he has left after leaving a note thanking her for her kindness and saying that he did not want to make trouble for her. Tanya is mortified not only for him, but for herself – a lonely woman struggling to raise her kids alone. It is all established without a word. Raymond’s acting is that good. Tanya returns to the living room and slaps here brother across the face. Kaban was – if only momentarily – not the protagonist but an observer of someone else’s story.

Great writing, great acting, great craft. This is how Hollywood even in the decline of its golden period could still fashion great cinema from simple human stories without melodrama and without pretense.

The Glass Wall (1953)

Columbia Pictures 82 min

Directed by Maxwell Shane

Screenplay – Ivan Shane, Maxwell Shane, and Ivan Tors

Cinematography by Joseph F. Biroc

Cast:

Vittorio Gassman – Peter Kaban

Gloria Grahame – Maggie Summers

Robin Raymond – Tanya aka Bella Zakoyla

Joe Turkel – Freddie Zakoyla (as Joseph Turkel)

Else Neft – Mrs. Zakoyla

Awards:

Locarno International Film Festival – 1953 – Maxwell Shane for Artistic Achievement

Cinematic Cities: New York 1953

The Subversive Truth of Noir: The Glass Wall (1953)

I was fed-up I guess

In the still-topical and very off-beat noir, The Glass Wall (1953), about post-war refugees and the nature of true compassion, Gloria Grahame gives a richly delicate performance as a young woman on the skids who helps a desperate asylum-seeker played with obvious sincerity by Vittorio Gassman. The streets of New York are rendered with a stunning chiaroscuro palette by DP Joseph Biroc. While the direction by Maxwell Shane could have been tighter, he also had a hand in the excellent script. A gem worth seeking out.

Bogart: “needful yet closed off, cynical and ruefully philosophical”

Andrew Dickos, in his perceptive survey of film noir, ‘Street With No Name: A History of the Classic American Film Noir’ (University Press of Kentucky 2002), from a discussion of the films of Nicholas Ray, has this to say about the noir protagonist and by reference Humphrey Bogart’s portrayal of Dixon Steele in Ray’s In a Lonely Place (1950):

“The world of Nicholas Ray’s noir films so clearly coincides with his vision of the dislocated, violent individual trapped in postwar America that it is fair to say the noir perspective displayed in these films is simply a variant of a vision apparent throughout most of his work. His characters anguish on a personal battleground where social forces structuring human discourse are internally disavowed and raged at and the most formidable opponent finally becomes one’s own conflicted self trying to function in the world… (p. 82)

“In Ray’s world of the angry and spiritually discomfited, Dixon Steele is more tormented by paranoia than any of the others. Certainly the project of screenwriting as an agency of moviemaking challenges one to achieve creative expression only to see the end product so often distorted, mutilated, or made banal by commercial forces. Steele faces this but is, moreover, self-lacerated, as many of Ray’s characters are, by the psychic urge to find meaning in a life personally and routinely bereft of it. This vision, cast in the noir mode and personified by Humphrey Bogart in one of his most intriguing roles, is perhaps better explained by reference to another Ray film, Rebel without a Cause. Victor Perkins described the planetarium sequence, as James Dean and his friends gaze upward at the universe while the narrator comments about gas, fire, and the insignificance of the planet’s impending destruction. “It is against this concept of man’s life as an episode of little consequence”, he wrote, “rather than against society, or his family, that Dean rebels.” * Dixon Steele emerges as a glamorous cultural variant of such rebellion. Violent but not knowing why, provocative but to what end, needful yet closed off, cynical and ruefully philosophical, Steele is, finally, Hollywood’s figure of a troubled man. And who better to personify such a postwar figure than Bogart?” (p. 87)

_______

* Perkins, V.F. ‘The Cinema of Nicholas Ray’, Movie, no. 9 (1963), pp. 4–10.

Noir Poets: Tupac Shakur

March 1997 Amin and Bunlay (Grade 7/8) Bonaventure Meadows Public School London, Ontario, Canada

California Love (1995)

Out on bail fresh outta jail, California dreamin

Soon as I stepped on the scene, I’m hearin hoochies screamin

Fiendin for money and alcohol

the life of a west side playa where cowards die and its all ball

Only in Cali where we riot not rally to live and die

In L.A. we wearin Chucks not Ballies (that’s right)

Dressed in Locs and khaki suits and ride is what we do

Flossin but have caution we collide with other crews

Famous cause we program worldwide

Let’em recognize from Long Beach to Rosecrans

Bumpin and grindin like a slow jam, it’s west side

So you know the row won’t bow down to no man

Say what you say

But give me that bomb beat from Dre

Let me serenade the streets of L.A.

From Oakland to Sacktown

The Bay Area and back down

Cali is where they put they mack down

Give me love!

Bodyguard (1948): “I keep meat warm”

A suspended cop is framed for the murder of his former boss after he takes on a job as the bodyguard for a meat-packing heiress.

An RKO programmer of 75 minutes, Bodyguard is an entertaining mystery thriller that harks back to the hard-boiled pulp published in the 20s and 30s by Black Mask magazine. The writers include a young Robert Altman. While it never presumes to go beyond its b-origins, as an early feature from director Richard Fleischer, better known for later b-noirs such as Follow Me Quietly (1949), Armored Car Robbery (1950) and The Narrow Margin (1952), the movie has some nicely conceived scenes that place it above the ordinary. Solid turns by tough-guy Lawrence Tierney as a framed ex-cop and the cutest girl-next-door Priscilla Lane as his girl, complete the package.

Fast-paced and breezy, and aided by snappy dialog, the picture is all about entertainment. No angst or femme-fatales, just a a good old yarn about the corrupt rich and their criminal machinations. The mystery is sustained with just the right hints so that when the bad guys are found out you are rewarded with having your half-held suspicions confirmed. The climax at the meat-packing plant has some ‘cute’ mis-en-scene involving a hog-saw and and a meat cleaver. Great fun.

These shots from the movie attest to its visual panache.

The Big Clock (1948): “the wrong people always have money”

The Big Clock opens with the dark silhouette of skyscrapers against a New York night with bordello jazz on the soundtrack. After a pan tensely edging right across the screen, the camera rests on and zooms into the mezzanine level of a modernistic office building with the signage ‘Janoth Publications’. An anxious man in a suit narrowly avoids a security guard as he sneaks into the mechanism of a large clock that dominates the foyer below. His voice-over relates the circumstances of a dire predicament and events flashback to the previous morning.

But this is about as noir as it gets. The guy inside the clock is a suave Ray Milland, a family guy working for a dictatorial publishing tycoon as the editor of Crimeways magazine. His boss is a gargoyle in a suite sporting a Hitler moustache, and with the nervous habit of sliding his flabby forefinger across his bushy upper lip. A man who knows the cost of everything and the value of nothing. Charles Laughton occupies the suit and the executive suite in a building of apt fascist modernist lines fashioned by the film’s art director, Hans Drier.

Director John Farrow and DP John Seitz infiltrate this place with smooth and flowing steps that despite their elegance somehow render the whole space rather flat. Office space is sterile at best, and the result is a ponderous unraveling of a story that borders on the tedious. But such spaces can be rendered with atmosphere. Look at how – and this is indeed ironic – the same Dreier and Seitz under the direction of Billy Wilder make an insurance office look interesting in Double Indemnity (1944).

To cut to the chase, Milland is being framed for a murder by murderer Laughton, who doesn’t know the true identity of the guy he is trying to frame. It sounds better than it plays out. The whole scenario is played too lightly and with no atmosphere. The source novel by Kenneth Fearing has lost something in Jonathan Latimer’s screenplay. Though the tycoon’s final misstep as he escapes into his personal elevator is savagely noir.

Thankfully the affair is saved by an uproarious turn from a supporting actress in a part that occupies less than seven minutes of screen time. British-born character actor Elsa Lanchester – Laughton’s wife and Mrs Frakenstein in the camp classic Bride of Frankenstein (1935) – is a zany bohemian painter, who by chance gets tangentially mixed-up with Milland and proceeds to steal the picture – there is a pun here you will recognise if you have seen the movie or watch the clip below. She keeps turning up and closes the movie with a neat scene of comic irony.

This is her story. She first appears in an antique shop where she and a drunken Milland in the company of the tycoon’s girlfriend haggle over a rather grotesque painting.

Summary Noir Reviews: Desperate Suspense and a Fallen Sparrow

Desperate (1947)

An uber cool Anthony Mann noir. Raymond Burr dominates as an avenging hood. Brilliant chiaroscuro lensing and crazy angles satisfy.

Mann’s Desperate marks the beginning of a prolific three year arc for the director which saw the production of five iconic noirs: Desperate (1947), Railroaded! (1947), T-Men (1947), Raw Deal (1948), and Border Incident (1949). While his legendary collaboration with master cinematographer John Alton did not begin until T-Men, DP George Diskant with Desperate can together with Mann take the kudos for the most stunning scene of the classic noir cycle, when a hapless trucker is given a going over in Burr’s dark hideout, where the only light source is a swinging room lamp put in motion by the victim’s body as it is pummeled across the room. The scene has been described by Carl Macek as “a stunning example of American expressionist film-making” (Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference, 1979). A clip of the scene was recently featured at filmsnoir.net here.

In Desperate a trucker is duped into a fur heist by a gang led by Burr, which goes wrong when Burr’s trigger-happy kid-brother kills a cop after the trucker flashes his truck’s headlights in a desperate attempt to alert the patrolman and the kid is left behind in the scramble to escape. The brother is caught, and soon after the trucker escapes his captors. The trucker, now pursued by the cops and Burr, hightails it with his pregnant wife. The script and direction are taut but the plot is less then plausible as the pursuit drags on. But the denouement played out on a tenement stairwell is classic Mann and is worth waiting for, and prefigured by a suspenseful sequence featuring a loudly ticking alarm clock.

Suspense (1946)

Monogram’s costliest feature a melodrama on ice only fires at the end when the absurd plot is put on ice. Olympic ice-skater Belita is hot!

Suspense directed by Frank Tuttle (This Gun for Hire (1942), Gunman in the Streets (France 1950), and Hell on Frisco Bay (1955)) features strong performances from the two leads: Barry Sullivan (Framed (1947), The Gangster (1947), Tension (1949), and Cause for Alarm! (1951)) as an ambitious homme-fatale, and Belita as the iconic blonde in a fatal love quadrangle. The plot revolving around a follies-on-ice venue is novel, as are the extended musical numbers featuring the very nubile Belita. But the story has a preposterous twist that stretches the suspension of incredulity. Burdened by this very real weakness, the picture just about comes apart. The movie is salvaged at the end after a murder propels the protagonists into a vortex of guilt, paranoia, and revenge. Director Tuttle and veteran DP Karl Struss, who won an Oscar for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in 1931, and worked on The Great Dictator (1940) and Journey Into Fear (1943), in the final scenes, reach a richly expressionist synergy.

The Fallen Sparrow (1943)

An anti-fascist thriller featuring a frenetic performance from John Garfield as a vet from the Spanish civil war battling post-traumatic stress and a Nazi spy ring. Compelling.

Garfield delivers a wonderfully nuanced portrayal as a guy suffering post-traumatic stress disorder after being captured and tortured by Nazis during Spain’s civil war. He returns to New York from a convalescent farm when he learns his best friend has been killed in suspicious circumstances. He thinks it is murder, and suspects a sinister pair of Austrian refugees, who have ingratiated themselves in a liberal and wealthy social set. The screenplay by Warren Duff, from a source novel by Dorothy B. Hughes, who wrote the stories for Ride the Pink Horse (1947) and In a Lonely Place (1950), is tight and works on the level of a thriller while deftly weaving Garfield’s psychological entrapment into the plot, by linking recurring hallucinations with the search for his friend’s killers. The dialog is snappy, and scenes between Garfield and a socialite girlfriend are nicely barbed and risqué. The lovely Patricia Morison who plays the ex is lusciously sexy and engaging – check out the gown she is wearing in her first scene – production code censor Breen must have been asleep to let that one through! The luminous Maureen O’Hara plays a diaphanous femme-fatale-cum-mata-hari. Her performance is so elegant that by the end of the film her true feelings still remain a tantalizing mystery. Director Richard Wallace (Framed (1947) and Tycoon (1947)) and noted noir DP Nick Musuraca fashion an accomplished mise-en-scène of fluid and flowing takes, moody lighting, and angled shots, ably assisted by Roy Webb’s evocative score, which received an Oscar nomination. There is a memorable peroration towards the end to cement the film’s political intent.

Prefiguring Postmodernism: Flashback in Film Noir

I am currently reading a fascinating book on the career of activist Hollywood writer and producer, Adrian Scott, ‘Caught in the Crossfire: Adrian Scott and the Politics of Americanism in 1940s Hollywood’, by Jennifer E. Langdon (2008 Columbia University Press), which focuses on the production by Scott of three seminal RKO noirs, Murder, My Sweet (1944), Cornered (1945), and Crossfire (1947).

In a chapter on the making of Crossfire, Langdon relates that one of the most radical changes Scott and screenwriter John Paxton made in the adaptation of Richard Brook’s source novel, ‘The Brick Foxhole’, was the use of flashback. Langdon goes on to expound a profoundly interesting take on the nature of the flashback in film noir:

flashbacks are a key narrative strategy in film noir, contributing to the genre’s existential exploration of truth and falsehood. Historian William Graebner, suggesting the ways in which film noir prefigured postmodernism, explains, “By interrupting a traditional, linear narrative, the flashback challenged the form strongly identified with progress: the story with a beginning, a middle, and an end, and open to all possibilities.” Explicitly connecting the ruptured narrative strategies of film noir to the pervasive postwar sense of contingency and doubt, he argues: “In the context of a military victory that seemed to have been won at the cost of demonstrating the inhumanity of humankind, and of a cold war that called for eternal vigilance, the ability of a cultural text to produce a conclusion consistent with, and implied in, everything that had gone before—what literary scholar Frank Kermode calls ‘the sense of an ending’ —withered and died.” * (p 85)

More on Langdon’s book in a future post.

________

* William Graebner, The Age of Doubt: American Thought and Culture in the 1940s (Boston: Twayne, 1981), 54, 145.