The greatest films noir of all time. Ambitious and perhaps presumptuous. But without apology or regrets.

A list of 65 movies which I rate 5-star – the top films noir. As have an aversion to rankings, my list of the best films noir is listed by year of production.

5 star Noirs Click on the title for the FilmsNoir.Net review |

||

| La Nuit de Carrefour | 1931 France |

Aka ‘Night at the Crossroads’. Early Jean Renoir poetics. Magically delicious femme-noir and a brilliant car chase at night. Moody and bizarrre! |

| You Only Live Once | 1937 US |

Fritz Lang and Hollywood kick-start poetic realism! Henry Fonda and Sylvia Sidney are the doomed lovers on the run. |

| Hotel du Nord | 1938 France |

Poetic realist melodrama of lives at a downtown Paris hotel. As moody as noir with a darkly absurd resolution. |

| Port of Shadows | 1938 France |

Aka Le Quai des brumes. Fate a dank existential fog ensnares doomed lovers Jean Gabin and Michèle Morgan after one night of happiness. |

| I Wake Up Screaming | 1941 US |

Early crooked cop psycho-noir. Redolent noir motifs, dark shadows, off-kilter framing and expressionist imagery. |

| The Maltese Falcon | 1941 US |

Bogart as Sam Spade the quintessential noir protagonist. A loner on the edge of polite society, sorely tempted to transgress but declines and is neither saved nor redeemed. |

| Journey Into Fear | 1943 US |

Moody Orson Welles’ noir. Exotic locales, sexy dames, weird villains, politics, wisdom, philosophy, and a wry humor. |

| The Seventh Victim | 1943 US |

“Despair behind, and death before doth cast”. The terror of an empty existence. Brilliant Lewton gothic melodrama. |

| Double Indemnity | 1944 US |

All the elements of the archetypal film noir are distilled into a gothic LA tale of greed, sex, and betrayal. |

| Laura | 1944 US |

Gene Tierney is an exquisite iridescent angel and Dana Andrews a stolid cop who nails the killer after falling for a dead dame. |

| Murder, My Sweet | 1944 US |

(Aka Farewell, my Lovely). The most noir fun you will ever have. Raymond Chandler’s prose crackles with moody noir direction from Edward Dmytryk. |

| Mildred Pierce | 1945 US |

Joan Crawford in classy melodrama by Michael Curtiz lensed by Ernest Haller. Self-made woman escapes morass of greed. |

| The Lost Weekend | 1945 US |

‘Most men lead lives of quiet desperation. I can’t take quiet desperation.’ Ray Milland against type on a bender. |

| Ride the Pink Horse | 1946 US |

Disillusioned WW2 vet arrives in a New Mexico town to blackmail a war racketeer. Imbued with a rare humanity. |

| Scarlet Street | 1946 US |

Classic noir from Fritz Lang. Unremitting in its pessimism. A dark mood and pervading doom of devastating intensity. |

| The Big Sleep | 1946 US |

Love’s Vengeance Lost. Darker than Dmytryk’s Murder, My Sweet. Bogart is tougher, more driven, and morally suspect. |

| The Killers | 1946 US |

Siodmak’s classic noir. Burt Lancaster’s masterful debut performance in a tragedy of a decent man destroyed by fate. |

| The Postman Always Rings Twice | 1946 US |

Fate ensures adulterous lovers who murder the woman’s husband, suffer definite and final retribution. |

| Body and Soul | 1947 US |

A masterwork. Melodramatic expose of the fight game and a savage indictment of money capitalism. Garfield’s picture. |

| Brighton Rock | 1947 UK |

Greatest British noir is dark and chilling. A cinematic tour-de-force: from the direction and cinematography to top cast and editing. |

| Nightmare Alley | 1947 US |

Predatory femme-fatale uses greed not sex to trap her prey in a hell of hangmen at the bottom of an empty gin bottle. |

| Nora Prentiss | 1947 US |

Doctor is plunged into a dark pool of noir angst in a turbo-charged melodrama of tortured loyalty and thwarted passion. |

| Out of the Past | 1947 US |

Quintessential film noir. Inspired direction, exquisite expressionist cinematography, and legendary Mitchum and Greer. |

| The Gangster | 1947 US |

Hell of a b-movie. Very dark noir ‘opera’ brutally critiques the ‘entrepreneurial spirit’. Bravado Dalton Trumbo script. |

| The Lady From Shanghai | 1947 US |

Orson Welles’ brilliant jigsaw noir with a femme-fatale to die for and a script so sharp you relish every scene. |

| T-Men | 1947 US |

Mann and Alton offer a visionary descent into a noir realm of dark tenements, nightclubs, mobsters, and hellish steam baths. |

| Act of Violence | 1948 US |

Long-shot and deep focus climax filmed night-for-night on a railway platform: the stuff noirs are made of. |

| Drunken Angel | 1948 Japan |

Aka ‘Yoidore tenshi’. Kurosawa noir. A loser doctor with soul takes on the fetid moral swamp of Yakuza degradation. |

| Force of Evil | 1948 US |

Polonsky transcends noir in a tragic allegory on greed and family. Garfield adds signature honesty and gritty complexity . |

| Hollow Triumph | 1948 US |

Baroque journey to perdition traversing a noir topography redolent with noir archetypes. Audacious and enthralling. |

| Raw Deal | 1948 US |

Sublime noir from Anthony Mann and John Alton. Knockout cast in a strong story stunningly rendered as expressionist art. |

| They Live by Night | 1948 US |

Nicholas Ray’s first feature. A tragedy of Shakespearean dimensions which transcends film noir. |

| Too Late For Tears | 1948 US |

Preposterous chance event launches wild descent into dark avarice and eroticised violence as relentless as fate. |

| Bitter Rice | 1949 Italy |

Aka ‘Riso Amaro’. Classic neo-realist socialist melodrama. Homme-fatale destroys a passionate innocent. A bad girl is redeemed and homme-fatale meets a gruesome noir end in an abattoir. |

| Border Incident | 1949 US |

Subversive expressionist noir from Dir Anthony Mann DP John Alton and writer John C Higgin indicts US agribusiness. |

| Criss-Cross | 1949 US |

Accomplished noir showcased by Siodmak’s masterful aerial opening shot into parking lot onto a passing car exposing the doomed lovers to the spotlight. |

| Stray Dog | 1949 Japan |

Aka ‘Nora inu’. Kurosawa’s ying and yang take on reality informs this 5-star noir: the pursuer could as easily have been the pursued. |

| The Reckless Moment | 1949 US |

Max Ophuls takes a blackmail story and infuses it with a complexity and subtlety rarely matched in film noir. |

| The Set-Up | 1949 US |

Robert Ryan is great as washed-up boxer in Robert Wise’ sharp expose of the fight game. Brooding and intense noir classic. |

| The Third Man | 1949 UK |

Sublime. An engaging cavalcade of characters in a human comedy of love, friendship, and the imperatives of conscience. |

| Thieves’ Highway | 1949 US |

Moody Richard Conte hauling fruit to Frisco. Rich socio-realist melodrama from Jules Dassin and A.I. Bezzerides. AAA. |

| Une Si Jolie Petite Plage | 1949 France |

Aka ‘Riptide’. Iron in the soul: savage irony, withering subversion, and desolation mark the rain-sodden angst of a young man’s end. |

| White Heat | 1949 US |

Fission Noir. Taut electric thriller straps you in an emotional strait-jacket released only in the final explosive frames. |

| Breaking Point | 1950 US |

Great John Garfield vehicle with strong social subtext. Much stronger than from the same source To Have and Have Not. |

| Caged | 1950 US |

Eleanor Parker leads a great female cast in a dark women’s prison picture with a savage climax and a gutsy downbeat ending. |

| D.O.A. | 1950 US |

Gritty on-the-street in-your-face melodrama of innocent act a decent man’s un-doing. Edmund O’Brien is intense. The goons rock! |

| In A Lonely Place | 1950 US |

Nick Ray deftly explores effect of isolation, frustration, and anxiety on the creative psyche as noir entrapment. |

| Night And the City | 1950 US/UK |

Dassin’s stark existential journey played out in the dark dives of post-war London as a quintessential noir city. |

| Sunset Boulevard | 1950 US |

Wilder’s sympathetic story of four decent people each sadly complicit in the inevitable doom that will engulf them. |

| The Asphalt Jungle | 1950 US |

Quintessential heist movie transcends melodrama and noir. A police siren wails: “Sounds like a soul in hell.” |

| The Sound of Fury | 1950 US |

Great noir! Outdoes Lang’s Fury and brilliantly prefigures Wilder’s Ace in the Hole. Climactic mob scenes mesmerise. |

| On Dangerous Ground | 1951 US |

City cop battling inner demons is sent to ‘Siberia’. A film of dark beauty and haunting characterisations. |

| The Prowler | 1951 US |

Van Heflin is homme-fatale in Tumbo thriller. Director Losey is unforgiving. Each squalid act is suffocatingly framed. |

| Ace in the Hole | 1952 US |

A savage critique of a corrupted and corrupting modern mass media. Billy Wilder’s best movie. Kirk Douglas owns it. |

| Clash By Night | 1952 US |

Cheating wife Stanwyck faces the music. Fritz Lang puts sexual license and existential entitlement on trial and wins. |

| The Big Heat | 1953 US |

Gloria Grahame as existential hero in Fritz Lang’s brooding socio-realist noir critique. |

| Crime Wave | 1954 US |

Andre de Toth noir masterwork set on the streets of LA is so authentic it plays for real with each character deeply drawn. |

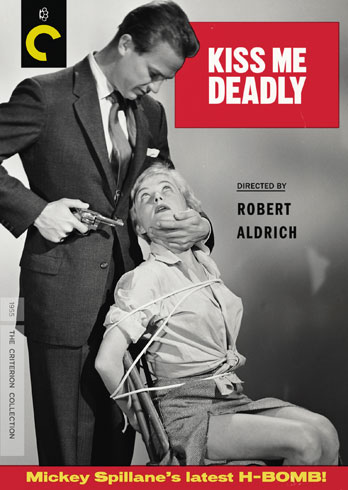

| Kiss Me Deadly | 1955 US |

Anti-fascist Hollywood Dada. Aldrich’s surreal noir a totally weird yet compelling exploration of urban paranoia. |

| Rififi | 1955 France |

Dassin’s classic heist thriller culminating in the terrific final scenes of a car desperately careening through Paris streets. |

| The Big Combo | 1955 US |

“I live in a maze… a strange blind backward maze’. Obsessed cop hunts down a psychotic crime boss in the best noir of 50s. |

| Sweet Smell of Success | 1957 US |

DP James Wong Howe’s sharpest picture. As bracing as vinegar and cold as ice. Ambition stripped of all pretense. |

| Touch of Evil | 1958 US |

Welles’ masterwork is a disconnected emotionally remote study of moral dissipation. Crisp b&w lensing by Russell Metty. |

| Underworld USA | 1961 US |

Fast and furious pulp from Sam Fuller. Revenge finds redemption in death up a back alley the genesis of dark vengeance. |

| A Colt is My Passport | 1967 Japan |

Aka ‘Koruto wa ore no pasupoto’. Hip acid Nikkatsu noir with surreal spaghetti-western score. |

| Klute | 1971 Japan |

Alan J. Pakula’s signature reworking of classic noir motifs in a masterly study of urban paranoia and alienation. Jane Fonda earned an Oscar for her brilliant portrayal of articulate b-girl the target of mystery psychopath. |