Category: Articles

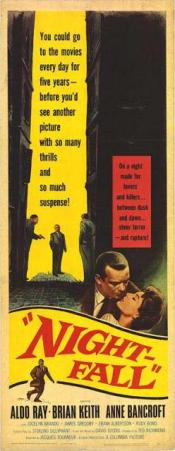

Nightfall (1957): Final curtain call for classic noir

Jacques Tourneur’s Nightfall signals the coming end of the classic noir cycle, followed only by Murder By Contract and Touch of Evil in 1958, and Odds Against Tomorrow in 1959.

Despite Tourneur’s directorial elan, excellent noir photography from Burnett Guffey, and a script based on a David Goodis novel, the movie clearly attests to the decline of the film noir cycle. The story of the innocent man entrapped by fate and on the run from both the cops and hoods has been played out many times before, and Tourneur does not manage to invest the scenario with any real tension. Even at 78 minutes the screenplay takes too long to reach its rather pat resolution.

Aldo Ray and Ann Bancroft in the leads are well cast, and the development of their relationship from a pick-up at a bar in LA and its flowering in the snow-drifts of Wyoming, is handled with economy and flair. The dialog is intelligent and the inter-play between two mis-matched hoods and their prey is strikingly good. The violence whether threatened or real is particularly noir. The two merciless hoods threaten to snap the legs of the protagonist on the boom of an oil rig, and the pitiless gunning down of a victim is still shocking to a jaded noir sensibility. But a climactic fight in the snow against an out-of-control snow plough is bereft of any true suspense, and even the final gruesome aftermath lacks real impact.

A Lighter Shade of Noir: Matinee Double-Bill

A Woman’s Secret (1949) and Hollywood story (1951), two flicks that carry a film noir classification on IMDB which I watched in the past week, I found to be hardly noir at all.

A Woman’s Secret, an RKO-feature, has great credentials. The movie is directed by Nicholas Ray from a screenplay from Herman J. Mankiewicz, with photography from George Diskant, and starring Maureen O’Hara, Melvyn Douglas, and Gloria Grahame. It starts off noir with a shooting off-screen, and the use of flashback in the narrative, but plays out as sophisticated melodrama with a biting wit, and some really funny slapstick when the wife of the investigating cop does her own snooping with a handbag carrying fingerprint powder and a giant magnifying glass. The story of the conflict between a naive young singer (Grahame) and her controlling mentor (O’Hara), has shades of All About Eve but this motif is not taken too seriously. The two female leads are charming, with Grahame displaying an engaging gift for comedy. Melvyn Douglas is as debonair as you would expect and takes the role of narrator and referee. Great fun.

Hollywood Story is a programmer from Universal that has a 50s television feel. Richard Conte is a producer in LA that wants to make a movie about the murder of a big silent movie director 20 odd years before, and his delving into the past has violent consequences. A strictly b-effort that plays well as a whodunit with noir atmospherics, and some really funny lines.

Christ in Concrete (1949): Simply a masterpiece

The moving simplicity of the Pietro Di Donato novel, Christ in Concrete, has been brought to the screen with rare sincerity. It is two hours of genuine human drama, which makes no concession to convention.

– Variety (1949)

The camerawork by C. Pennington Richards is some of the best of the era, with the city streets, darkened hallways, and construction sites void of any softened corners guaranteed by Hollywood of the 1940s. With Dmytryk, Richards gave Christ in Concrete an astonishing look, which manages to straddle and suggest both film noir and Italian neo-realism. The deep focus crisp black-and-white photography evokes a handful of strong movies yet to be made, including On the Waterfront, Edge of the City, America, America, Sweet Smell of Success, Touch of Evil, and Pickup on South Street. Visually, Christ in Concrete looks like the most influential movie nobody ever saw… Christ in Concrete shares its rough-edged moral outrage with Visconti’s La Terra Trema but its gilded professionalism with Wilder’s Double Indemnity. It’s a knockout combination. Dmytryk found some kind of artistic voice in exile in England unlike any heard from him before or since.

– Matthew Kennedy, Bright Lights Film Journal (Nov 2003)

Based on the novel by Italo-American Pietro Di Donato, Christ in Concrete (aka Give Us This Day), a powerful leftist denunciation of capitalism from director Edward Dmytryk, had to be filmed in the UK, and was buried a few days after its US release by a reactionary backlash. Telling the story of Italian immigrant building workers and their families in Brooklyn during the Depression, the film is the closest an Anglo-American movie ever got to the aesthetic and socialist outlook of Italian neo-realism. Teeming tenements and residential streets are shot with a provocatively gritty realism and film noir atmospherics.

The cast is superb with particularly powerful performances from the two leads, Sam Wanamaker and Lea Padovani, who embody the immigrant experience, which is so imbued with vitality and compassion that the film soars above any other similar work of the period. Enriched by a poetic script, the innovative cinematography of C.M. Pennington-Richards, outstanding art direction from Alex Vetchinsky, and a brilliantly evocative score by Benjamin Frankel, the movie is a revelation.

The opening scene in a deprived urban locale that follows a drunken man from the street and up the stairs of a dirty tenement building is a tour-de-force. An inspired mise-en-scene and a moving camera that follows the action from below Ozu-style, framed by the drama of the musical motifs, had me enthralled. This scene and the rest of the movie, except for panaromic shots of New York shown in the opening credits, were filmed in a studio lot in Denham, England!

Film as art, Christ in Concrete is simply a masterpiece.

Double Jeopardy (1955): Pulp Heaven

A 70 min b-feature from Republic Pictures, Double Jeopardy, is an unpretentious thriller, only tangentially noir, and with a high sleaze factor. The good guys are wooden and boring, and the bad guys irredeemably bad. A boozy blackmailer and his cheap wife are the focus and carry the picture. Pulp heaven.

The Garment Jungle (1957): Gia Scala’s Picture

The Garment Jungle, a contemporary expose of New York garment employers’ use of racketeers to keep unions out, disappoints. Finished by director Vincent Sherman after Robert Aldrich (Kiss Me Deadly) left production towards the end of shooting, for a Columbia a-feature it is largely set-bound, and suffers for it.

The whole affair sags and ends with a weak resolution. Lee J. Cobb in the lead is sadly flat. Robert Loggia as an Italo-American union organiser is strong and the performance of the tragic Gia Scala as his young wife dominates the picture. She is palpably alive on the screen and thoroughly immersed in her role. The sequence where she is introduced is the film’s highlight. Shot at a union dancing-class on a steamy-night where the dance music is a dissonant counterpoint to the drama, she is by turns sensual, fiery, gentle, and despairing. Here and in the external shots on the streets of NY, when they are used, the mise-en-scene and cinematography are truly inspired. We can commend cameraman Joseph F. Biroc, but who directed these scenes? My bet was Aldrich.

Silver and Ward list the movie in Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference, and to my mind ‘invent’ some film noir connections in the mise-en-scene and the lighting of some scenes. But For me The Garment Jungle is strictly melodrama.

The Woman on Pier 13 (1949): Better Wed than Red

A former member of the US Communist Party in a management

job on the San Francisco waterfront is blackmailed by the Party

It is with some irony that 60 years on it is the greed of bankers and not the ideology of leftists that has brought global capitalism to the brink of collapse, so take the red-menace propaganda here with a good dose of salt and you have a top film noir.

The Woman on Pier 13 (original title I Married a Communist) was a pet project of RKO boss Howard Hughes and it is said by some was a litmus test to sniff out reds in the ranks. His meddling delayed the movie’s release until 1951 after HUAC’s halycon days were past, and it bombed at the box office.

The screenplay, which despite criticism by most film critics as being far-fetched, to my viewing is quite solid, has the ‘commies’ work as a bunch of hoods. This conceit makes the script and the story compelling, with both melodramatic and thriller arcs. RKO stringer Robert Stevenson (Walk Softly, Stranger) does a solid job of directing, with stunning noir visuals by veteran noir cameraman Nicholas Musuraca.

The cast is particularly strong. Robert Ryan plays the former commie, and the lovely Laraine Day (The Locket) his wife. Thomas Gomez is a ruthless commie boss, with Janis Carter (Night Editor, Framed, I Love Trouble) as an undercover commie femme-fatale who mixes politics and love, and William Talman (Armored Car Robbery, The Racket, The Hitch-Hiker, City That Never Sleeps, Big House USA ) is convincing as a carnie moonlighting as a commie hit-man – in his first role.

The story never flags, and eroticized and violent noir pyrotechnics make for an enthralling and wild roller-coaster ride. When Ryan is first confronted by his Party blackmailer at a warehouse, a Party member suspected of treason is trussed and thrown in the Bay to drown while Ryan watches. Later a protagonist is run down by a car in cold blood by hit-man Talman. That same night Gomez pushes a woman out of an apartment window, and the sister of the guy run-down by Talman tracks him down and poses as a wife who needs her husband out-of-the-way Double-Indemnity style. The scenes between the two are erotic dynamite, and the perversity of Talman as the wise-cracking hit-man on the make boasting about his latest job make Tommy Udo (Kiss of Death) look like a kindergarten teacher.

A solid downbeat ending after a spectacular shoot-out on the wharves satisfies and has a redemptive focus.

They Made Me a Killer (1946): “You asked for it sister”

“Come on Jack let’s dance.”

“Go away will ya. Gotta get this barrel straight.”

“Too bad that gun can’t cook!”

“Well that makes you both even.”

An obscure programmer that goes for just 64 minutes, They Made Me a Killer, is a tidy little thriller. An innocent guy is framed for a bank heist after a crooked dame sets him up, and faces a murder rap for the killing of a security guard and a cop. He makes a break at a hospital after a guy who could corroborate his innocence dies without making a statement to the cops. It is is non-stop action with a neat romantic interest, and an inventive technical ruse to get the evidence the guy needs to secure his freedom.

The hospital escape scene is distilled noir. The fugitive slugs a cop in the back of the head with the cop’s gun, and then tips the bed with body of the guy that has just died still in it over another cop! He makes his final escape from a window after knock-out punching a female nurse in the face! And he ain’t no saint: he gets the girl and his freedom only after an attempt to turn-up the loot and keep it for himself fails.

Great b-feature!

The Man Who Cheated Himself (1949): True Noir

In San Francisco a middle-aged cop attempts to cover-up a murder committed by his rich girl-friend and being investigated by him and his rookie detective brother.

The only film ever produced by Jack M. Warner Productions, The Man Who Cheated Himself is a superbly crafted b-noir of 81 action-packed minutes. Under the tight control of director Felix E. Feist (The Devil Thumbs a Ride, Tomorrow Is Another Day, This Woman Is Dangerous ) even minor exposition scenes are focused on moving the compelling narrative forward. The film is shot both with economy and flair by Russell Harlan (Gun Crazy, The Thing from Another World, The Blackboard Jungle, King Creole, Rio Bravo). A solid script from Seton Miller (Dust Be My Destiny, Ministry of Fear, Convicted) deftly handles the tense sub-text.

The performances are solid all-round. The cop is played Lee J. Cobb, his girl-friend by Jane Wyatt, with John Dall, of Gun Crazy fame, in his last film role as Cobb’s brother. Cobb’s acting is inspired as the hard-bitten cop who by his own admission has let a woman he can’t trust get “under his skin”. Wyatt impresses as the femme-noir, and Dall is convincing as the brother who suspects Cobb is hiding something.

Most of the film is shot on the streets of Frisco in deep focus and this gives the picture a gritty realist feel. The highlights are three brilliant scenes: one in the middle and two at the end of the movie.

In the first, in a typically noir twist, the murder weapon, which had been thrown into the river, surfaces as the gun used to gun-down a store-keeper in a robbery. While serving as the catalyst for the brother’s suspicions, the scenes where the hood is trailed and caught is a bleak unsentimental vignette of a young man’s fall into criminality. The emotional power behind this sequence is left to the audience to develop. The final interrogation scene is stunningly shot and lit from a low angle.

In the second, Cobb and Wyatt, holed-up in an abandoned prison at the foot of the Golden Gate bridge, are hiding from Dall who is searching the long hallways and metal stairwells. Cobb and Wyatt are concealed atop a guard tower out of Dall’s direct sight when the wind takes Wyatt’s scarf. This McGuffin brilliantly deepens this already tense sequence as the scarf wraps itself against a pillar, and then taken again by the wind floats down into the prison’s central courtyard as Dall enters it.

Lastly, the final scene in the picture in a court-house has to be one of the most brutally frank and downbeat endings in the noir canon. Played without words, the two pratoganists’ actions and expressions deliver an acid resolution totally devoid of pretence or sentiment, and marked only by Cobb’s weary bemusement as he ponders his fate, after seeing his distrust finally vindicated.

A fantastic movie and a great noir.

Impact (1949): Noir Mash-Up

A United Artists release of 111 minutes, Impact looks like an A-movie wearing a B-suit: it doesn’t fit. The movie starts off noir in San Francisco, veers into bucolic redemption hokum in a small mid-western town, and then returns to Frisco for a turn at melodrama, ever ready to lapse into a comic interlude – and even slapstick. The plot is entirely derivative, with obvious parallels to Fritz Lang’s Fury (1936) and Busby Berkeley’s They Made Me a Criminal (1939). A cheating wife conspires with her lover to kill her wealthy husband, but the ill-planned job is botched, the husband survives but is believed dead, and the wife is charged with his murder.

The direction by Arthur Lubin is tight and the deep-focus photography on the streets of Frisco from Ernest Laszlo (Manhandled, DOA, M (1951), The Well, Kiss Me Deadly, The Big Knife, While the City Sleeps) is top-notch, particularly in a pursuit though Chinatown late in the picture, and during the murder attempt on a mountain road at night near the beginning of the picture which is solidly noir in its immediate fiery and darkly dramatic aftermath.

The dames hold this picture together. Helen Walker is a treat as the conniving wife of the businessman played by Brian Donlevy, who sleepwalks through the picture. Ella Raines is the wholesome country girl who falls for Donlevy, and Anna May Wong is engaging as the wife’s maid. Veteran character actor Charles Coburn is polished as a cop.

Surprisingly it all seems to hang together well enough, and on balance is quite enjoyable.