Mister Buddwing is a late monochrome portrait of amnesia played out in almost surreal fashion on New York City streets. There is only a tenuous connection with noir, and this relates more to the loss of identity trope than a broader concern with alienation in the modern metropolis.

James Garner wakes up in Central Park with amnesia. The only clues to his identity are a couple of pills, a phone number scrawled on a slip of paper, a train timetable, and an engraved cygnet ring. He is well-dressed in a suit and tie, and well-polished brogues. The opening scenes are from the protagonist’s POV, as in Dark Passage and The Lady in the Lake, until Garner sees himself reflected in a glass door. Embarking on a search for his identity he rings the telephone number and begins a day and night spent traversing the city and encountering a series of women he strangely mistakes for a woman called Grace. Meantime he gives himself the moniker of “Sam Buddwing”. The encounters and the city’s streetscapes grab your attention. Overall the script is uneven with the overarching story weaker and less convincing than the episodic vignettes that propel the action. It is these episodes that entertain, with some rally sharp absurdist humor, and great cameos from the actresses who variously portray the women Sam pursues.

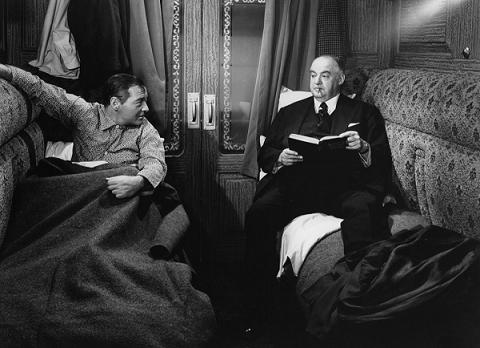

The film is best described as a crazy dream disturbed by waking moments of lucidity and lapses into banality. Garner as Sam has a certain charm but his less than stellar performance means the heavy load is carried by the other players. The first encounter is with the scruffy dame who answers Sam’s phone-call, played nicely by an ageing Angela Lansbury, who “puts out” offering the guy coffee, a hug, and some lucre; and sends him on his way. A hungry Sam then has an hilarious breakfast with the Jewish owner of a hash-house. Followed by a taxi-ride – a deftly written and sharp New York cabbie vignette – with Sam pursuing a female college student (Katharine Ross), who he thinks is his wife Grace. This interlude is the weakest with an overly long and overwrought fantasy sequence, but is redeemed by a coda that brings together a menagerie of Greenwich Village types; a hapless cop, nascent hipsters and beats, a gay guy, and a vagrant who thinks he is God – “really Kooksville”. Sam then hooks up with a quirky young off-broadway actress payed beautifully by Suzanne Pleshette. She breathes real life into the picture at this point with her beauty, her charm, and her street-smarts. While the fantasy episode this woman provokes tends to melodrama, Pleshette invests the sequence with a real pathos. Finally, Sam encounters a wealthy lush who likes to slum it in taxis, played with relish and boozy charm by a blonde Jean Simmons. The best scene in the picture then follows when Garner and the blonde crash a high-stakes crap game in a low-rent gambling den. This is a darkly-lit bravura sequence where the camera of DP Ellesworth Fredericks goes into contortions. The bit-players do a sterling job in creating the emotion and rising delirium of being on a roll.

The movie has received a bad rap from critics, including a withering review in the New York Times on its release. There are deep flaws, yes. The direction could have been tauter and the screenplay less melodramatic – the final scene is overly cliched and a let-down. But what director Delbert Mann and cameraman Fredericks have done is created a memorable portrait of a great city with both its grandeur and its desolation, together with a cavalcade of worthy denizens that give a real flavour of the zeitgeist. There is certainly also a high degree of elegance and craft in the intelligent use of close-ups, tracking, aerial, and low-angle shots that command and sustain visual interest. The outside deep-focus scenes have a neo-realist astringency and sad beauty, and many compositions linger in the memory. An edgy minimalist jazz score by Kenyon Hopkins adds a nice contemporary feel.

A must-see portrait of New York on the cusp of the Swinging Sixties, which follows in the tradition of films like The Naked City, Odds Against Tomorrow, and Sweet Smell of Success.

Thanks to Cigar Joe for the heads up on this recent Warner Archive DVD release.