Edie – Edie Johnson / Mrs. John Biddle (Linda Darnell)

Dr – Dr. Dan Wharton (Stephen McNally)

Edie – Look, if you don’t mind, I gotta get dressed now.

Dr – Are you going to work?

Edie – I work nights.

Dr – At what?

Edie – I’m a carhop in a drive-in. Anything wrong with that?

Dr – No, nothing at all.

Edie – It’s none of your business what I do. It’s a respectable job, and I pay my own way.

Dr – And you’re not living in Beaver Canal anymore.

Edie – Yeah, I’ve come up in the world. I used to live in a sewer. Now I live in a swamp. How do those babes do it in the movies? By now I oughta be married to the governor… and paying blackmail so he don’t find out I once lived in Beaver Canal.

Dr – The point is you got out.

Edie – Five blocks away.

Dr – Five million blocks – what’s the difference? You hate Beaver Canal. You hate what it stands for.

Edie – You talk like I was a poet or a professor. I found an open manhole, and I crawled out of a sewer. Wouldn’t anybody?

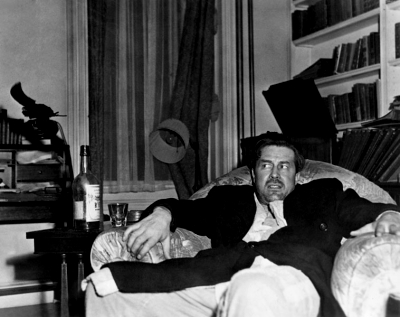

All concerned with the Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s No Way Out (Fox 1950), should have been justly proud of this ground-breaking movie. The story of a young black intern’s struggle against the prejudice of a deranged criminal confronts the issue of race head-on. This said, there are weaknesses. The otherwise great script by Mankiewicz and his collaborator Lesser Samuels veers too often towards melodrama, and racism is portrayed as largely a phenomenon of the white lumpenproletariat. Institutionalised prejudice – the wider cause of racial disadvantage – is ignored. Within these constraints a strong cast delivers an emotionally intense and harrowing depiction of race hatred at the level of the personal. Sidney Poitier in his first major film role is convincing as the young doctor, and he shows a wide emotional range. Richard Widmark as the foul-mouthed off-the-wall bigot is searing and dominates all his scenes. Stephen McNally as the chief resident of a city hospital and Poitier’s mentor is solid. But to my mind, the film’s acting plaudits must go to the beguiling Linda Darnell as the divorced wife of Widmark’s brother in crime, and the uncredited black actress Amanda Randolph as McNally’s housekeeper. What a terrible irony: a black actress who has a not insignificant role is not even credited!

Gladys – Dr. Wharton’s Housekeeper (Amanda Randolph uncredited)

Edie – Gladys, what do you do on your day off, like today?

Gladys – Oh, go sit in the park. Maybe go to church, maybe to a movie. Come suppertime, I go somewhere and cook.

Edie – Where?

Gladys – Friends. I fix ’em a good supper.

Edie – Some day off.

Gladys – [Chuckles] I like it. I’m a good cook. It’s somethin’ I can do better than other people. It makes me a somebody. Gives me a reason to be alive. Everybody gotta have that.

Edie – Or a reason not to be.

‘No Way Out’ is a very noir title informing the recurring noir motif of entrapment, and in this movie we have this motif woven seamlessly with three different threads: the young doctor struggling to find a way to save his career after he is accused of killing Widmark’s brother during a spinal tap procedure; Widmark trapped within his own paranoid bigotry; and Darnell in the face of Widmark’s venomous manipulation, desperately trying to keep the small advancement she has achieved after escaping her deprived social origins. Poitier’s struggle is the stuff of melodrama with his salvation assured, and tangentially noir. Widmark’s hood is mentally unhinged and full of hate, but even he in his pain-addled rantings at the climax is given a shot at justification, and his fate is pathetically cathartic, with Poitier sadistically applying with unbridled hate a tightening tourniquet around Widmark’s bleeding leg. The mis-en-scene of this closing scene is heavily symbolic: the makeshift tourniquet is fashioned from Darnell’s scarf and is tightened using Widmark’s gun after it has been emptied of bullets.

The overwhelming noir theme is Darnell’s redemption. A redemption she surely owns but that is equally owed to the decency of Randolph as the black housekeeper, and to Poitier’s demonstration of a morality that goes beyond vengeance and personal hatred. A white woman is redeemed by her decent self opening to the other: black people who show her a path to a life of decency free of prejudice and self-loathing. A great movie and a great noir.

Luther – Dr. Luther Brooks (Sidney Poitier)

Ray – Ray Biddle (Richard Widmark)

Edie – You all right?

Luther – [Wounded] My arm. Maybe my shoulder. I can’t tell.- It’s not so bad.

Ray – [Gasping] My leg! [Crying ] It tore. Somethin’ tore in my leg. [Crying Continues] It’s- It’s bleedin’. It’s bleedin’ hard. Please!

Edie – Let it bleed.

Ray – [Groaning ]

Edie – Tear it some more. Let it bleed fast.

Luther – You’ll have to help me.

Edie – To do what?

Luther – Whatever I can to keep him alive.

Edie – Why? What for? A human being’s gotta have a reason for bein’ alive. He hasn’t got any. He’s not even human. He’s a mad dog. You kill mad dogs, don’t ya?

Luther – Don’t you think I’d like to? Don’t you think I’d like to put the rest of these bullets through his head?

Edie – Then go ahead.

Luther – I can’t.

Edie – Why not?

Luther – Because I’ve got to live too.

Edie – Then give it [gun] to me.

Luther – You’ve got to live.

Edie – I will, believe me – happy as a bird with him dead.

Luther – Please help me. No. Look, he’s sick. He’s crazy. He’s everything you said. But I can’t kill a man just because he hates me.

Edie – What do you want me to do?

Luther – Take your scarf off. Put it around his thigh. There. And tie a knot. Not too tight.

Ray – [Groans]

Edie [to Luther] – You sure you’re all right?

Luther – Thanks.

Edie – [Siren Wailing In Distance] They took their time gettin’ here.

Luther – Don’t cry, white boy. You’re gonna live.

Ray – [Sobbing]… [Sobbing Continues]