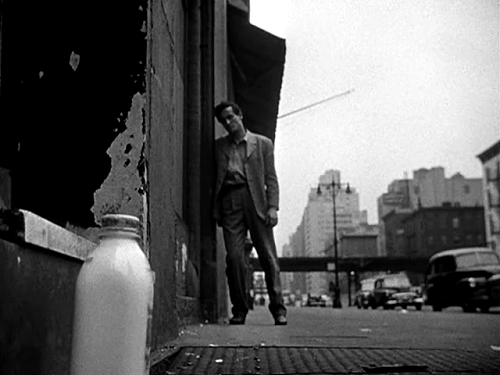

Out of the Fog (1941), the screen adaptation by Robert Rossen and Irwin Shaw of Shaw’s play, The Gentle People, written for The Group Theater in New York in 1939, wears it’s lefist heart on it’s sleeve and has dated badly. Anatole Litvak’s direction is workman-like only, and while James Wong Howe’s camera suitably renders a fog-laden set as the Brooklyn wharf-side, it is to little avail. Not even John Garfield as the cheap protection racketeer and Ida Lupino as the ‘ordinary’ girl to Garlfield’s homme-fatale, can save the enterprise. Studio hacks so diluted the trenchant play’s down-beat critique of capitalism and anti-fascist intent, that the contrived ending is played for laughs and the heroes come out looking as amoral as their victim. This moral ambivalence and the dark photography give the movie a noir tendency.

The film has one bright spot in a Russian sauna when two rocking-chair revolutionaries hatch their plot to kill the racketeer. George Tobias as a bankrupt store-keeper delivers a riveting background monologue on his fate. The writing brilliantly employs decidedly Jewish humor in a witty critique that runs to the core of the story, and is totally subversive of the melodrama played out in the foreground.

Out of the Fog (1941), the screen adaptation by Robert Rossen and Irwin Shaw of Shaw’s play, The Gentle People, written for The

Group Theater in New York in 1939, wears it’s lefist heart on it’s sleeve and has dated badly.

Anatole Litvak’s direction is workman-like only and while James Wong Howe’s camera suitably renders a fog-laden set as the

Brooklyn wharf-side, it is to little avail. Not even John Garfield as the cheap protection racketeer and Ida Lupino as the

‘ordinary’ girl to Garlfield’s homme-fatale, can save the enterprise. Studio hacks so diluted the trenchant play’s down-beat

critique of capitalism that the contrived ending is played for laughs and the heroes come out looking as amoral as their

victim. This moral ambivalence and the dark photography give the movie a noir tendency.

The film however has one bright spot when the two rocking chair revolutionaries hatch their plot to kill the racketeer in a

Russian sauna. George Tobias as a bankrupt store-keeper delivers a rivetting background monologue on his fate. The writing is

brilliantly employs decidely Jewish humor in a savage critique runs to the core of the story, and is totally subversive of the

cheap melodrama played out in the foreground. The scene is featured in the following edited clip.