a noir car

FilmsNoir.Net – all about film noir

the art of #filmnoir @filmsnoir.net | Copyright © Anthony D'Ambra 2007-2025

a noir car

American films noir from the classic cycle have essentially the same narrative structure as other Hollywood movies, and that the entertainment value of a movie lies in the delicate balancing of pleasure and anxiety.

Yesterday I started reading Frank Krutnik’s ‘In a Lonely Street: Film noir, genre, masculinity’ (2001), a book which explores the film noir narrative structure as a defining element with a focus on movies of the 1940s. Early on Krutnik argues that American films noir from the classic cycle have essentially the same narrative structure as other Hollywood movies, and that the entertainment value of a Hollywood movie lies in the delicate balancing of pleasure and anxiety. Krutnik says that “In submitting to an engagement with the fictional process, the spectator offers in exchange not just money (at the box-office) but also a psychical/emotional investment.” (p 5)

For me anxiety and the more prevalent downbeat resolution of the narrative in film noir are the defining aspects.

Krutnik outlines the classic Hollywood narrative in these terms: a crisis or destabilizing event occurs that is resolved by an heterosexual male to impress and win a passive female. (Any over-simplification is to my account.) Where noir diverges is that the male is typically an anti-hero, the female not passive and many times the protagonist. The latest movie I have watched nicely illustrates this.

A Dangerous Profession an RKO b from 1949 is an undistinguished crime movie competently made and well-acted. A former cop turned bail bondsman is asked to bail out a guy charged with a heist and the killing of a cop, and who is the husband of a former lover, and he lets his infatuation take-over. The woman is attractive and we are not sure she can be trusted, but she does little anyway. The protagonist has to sort things out after the husband jumps bail and is murdered. He solves the mystery, apprehends the crooks, and gets the girl. Order is re-established. Some have classified this movie as noir, which it clearly isn’t. A film noir would probe the psychology of the protagonists and perhaps uses expressionist stylistics to represent mood and character. There would certainly be a degree of ambiguity as to the morality of the players and their motivations, and there would more than likely be a downbeat ending or a resolution that came at a significant cost. A good example is The Big Sleep (1946) .

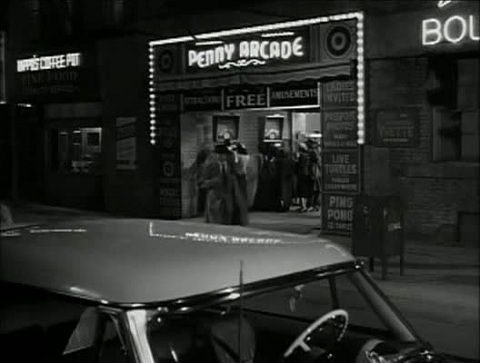

Filmed on the streets of New York and in deep focus, The Window challenges Jule’s Dassin’s The Naked City (1948) as the first documentary noir…

The Window, an RKO b-noir that was a big box office hit in 1949, features an Oscar-winning performance from child-actor Bobby Driscoll as a kid who has told too many tall stories to be believed when he actually witnesses a murder. Based on a story by Cornell Woolrich, the movie is a tight thriller of entrapment, where the tenements of working-class New York are a prison few escape. Filmed on the streets and in deep focus, The Window challenges Jule’s Dassin’s The Naked City (1948) as the first documentary-style noir – it was actually completed two months before The Naked City in January 1948. Director Ted Tatzlaff and DPs Robert De Grass and William Steiner fashion a cityscape and built spaces that express a deeply oppressive ambience.

The Window (RKO 1949) 73min

Directed by Ted Tetzlaff

Writing credits: Cornell Woolrich (story) and Mel Dinelli (screenplay)

Cast:

Barbara Hale – Mrs. Mary Woodry

Arthur Kennedy – Mr. Ed Woodry

Paul Stewart – Joe Kellerson

Ruth Roman – Mrs. Jean Kellerson

Bobby Driscoll – Tommy Woodry

Original Music by Roy Webb

Cinematography by Robert De Grasse William Steiner

The two films noir covered in this edition of the digest are less than gripping. But they do raise interesting issues… Conflict (1945) and Rogue Cop (1954)

The two films noir covered in this edition of the digest are less than gripping. But they do raise interesting issues.

Conflict (1945) has Humphrey Bogart as an engineer in a loveless marriage who bumps off his wife so that he can make a play for her younger sister. The script is good and an enticing mystery twisted into psychological entrapment should have been gripping, but sadly Curtis Bernhardt directs a rather somnambulant cast. Although Bogie tries hard, both Alexis Smith as the younger sister and Sidney Greenstreet as a shrink on a diet are flat. This said, the sleepiness has a fascinating counterpoint. Early on after a car accident Bogart falls into a coma – a swirling whirlpool tells us that – and he wakes up in a hospital bed with murder on his mind. From this point Bernhardt and his DP Merritt Gerstad deftly craft a dream-like atmosphere that is really intriguing. While some mysterious events and Bogart’s spiral into paranoia had me thinking of a ‘Woman-in-the-Window’ resolution, a nice though strangely anti-climactic twist proves otherwise. Interesting also is a degree of rare ambiguity. We never know Smith’s true feelings for Bogart, and he actually makes a selfless if not quite noble call at the height of his paranoia.

Rogue Cop (1954) on paper ticks most of the right noir boxes: a screenplay by Sydney Boehm based on a novel by William P. McGivern; an a-list cast including Robert Taylor, Janet Leigh, and George Raft; lensing by John Seitz; and journeyman director Roy Rowland. Taylor plays a crooked cop in league with mobster Raft, who has to face the music when his younger honest cop brother is pressured to turn bad. The whole affair falls flat with Taylor at his wooden worst, and while Leigh and Raft try harder, they cannot enliven proceedings against the mud tide of Rowland’s leaden direction. DP Seitz is largely wasted, with the only interesting visuals under the opening credits. Boehm’s script lacks subtlety, and would have disappointed McGivern who was not a writer content with simple verities or homilies. Imagine what Fritz Lang could have done and weep: a lesson in how not to make a film noir.

Strange brew, kill what’s inside of you

She’s a witch of trouble in electric blue

In her own mad mind she’s in love with you, with you

Now what you gonna do?

Strange brew, kill what’s inside of you

She’s some kind of demon messing in the glue

If you don’t watch out it’ll stick to you, to you

What kind of fool are you?

Strange brew, kill what’s inside of you

On a boat in the middle of a raging sea

She would make a scene for it all to be ignored

And wouldn’t you be bored?

Strange brew, kill what’s inside of you

Strange brew, strange brew

Strange brew, strange brew

Strange brew, kill what’s inside of you

Strange Brew – Cream (1967)

Film Noir Origins: Angels Over Broadway (1940) Directors Ben Hecht & Lee Garmes | DP Lee Garmes | Art Director Lionel Banks…

Angels Over Broadway (1940) Directors Ben Hecht & Lee Garmes | DP Lee Garmes | Art Director Lionel Banks

Film Noir Origins: Métropolitain (France 1939) Director Maurice Cam | DP’s Nicolas Hayer, Pierre Méré, and Marcel Villet… …

Métropolitain (France 1939) Director Maurice Cam | DP’s Nicolas Hayer, Pierre Méré, and Marcel Villet

Film Noir Origins: Private Detective 62 (Warner Bros. 1933) Director Michael Curtiz | DP Tony Gaudio | Art Director Jack Okey…

Film Noir Origins: Paid (1930) – Director Sam Wood | DP Charles Rosher | Art Director Cedric Gibbons….

Paid (1930) Director Sam Wood | DP Charles Rosher | Art Director Cedric Gibbons

TV Noir: The Twentieth Century by Ray Starman and Screwball Comedy and Film Noir: An Analysis of Their Imagery and Character Kinship by Thomas C. Renzi…

A couple or recent publications have come to my attention.

TV Noir: The Twentieth Century by Ray Starman

Starman covers 50 prime-time television series over 50 years from Treasury Men (1950-55) to the X-Files (1993-99). For those like me who grew up watching b&w TV in the 50s and 60s there is a wealth of noir analysis and a big dose of nostalgia, with chapters on shows like Dragnet, The Naked City, The Untouchables, Peter Gunn, 87th Precint (a personal favorite), The Fugitive, and Streets of San Francisco. Available from Amazon.

Screwball Comedy and Film Noir: An Analysis of Their Imagery and Character Kinship by Thomas C. Renzi

A comparative analysis of Screwball Comedy and Film Noir. Despite their contrast in tone and theme, Renzi sees Screwball and Noir as having many common narrative elements in common, and discusses their historical development and related conventions, offering detailed analyses of a number of films, among them The Lady Eve and His Girl Friday on the Screwball side, and Gilda and Sunset Blvd. on the Noir side. Available from Amazon.