I just came across this book of film noir posters from the classic period of film noir: Crime Scenes: Movie Poster Art of the Film Noir : The Classic Period : 1941-1959 by Lawrence Bassoff (Paperback).

Available from Amazon from US$20.

FilmsNoir.Net – all about film noir

the art of #filmnoir @filmsnoir.net | Copyright © Anthony D'Ambra 2007-2025

I just came across this book of film noir posters from the classic period of film noir: Crime Scenes: Movie Poster Art of the Film Noir : The Classic Period : 1941-1959 by Lawrence Bassoff (Paperback).

Available from Amazon from US$20.

Virtual-History.Com is a great site for tracking down books on film noir generally and any books that refer to a certain film. For example this search link will not only return books on The Third Man, but a list of books that substantially reference that film:

Books about The Third Man:

Rob White, The Third Man, London, 2003

Books with substantial mentioning of The Third Man:

David Zinman, 50 Classic Motion Pictures, The Stuff That Dreams Are Made Of, New York, 1970

JerryVermilye, The Great British Films, Secaucus, N.J., 1978

Ann Lloyd (editor), Movies of the Forties, London, 1982

Anthony Slide, Fifty Classic Films 1932-1982, A Pictorial Record, New York, 1985

Neil Sinyard, Classic Movies, London, 1993

William Hare, Early Film Noir, Greed, Lust and Murder Hollywood Style, Jefferson, North Carolina, and London, 2003

Books with entries on The Third Man:

Michael F. Keaney, Film Noir Guide, 745 Films of the Classic Era, 1940-1959, Jefferson, North Carolina, and London, 2003

For US$9.99 you can download the 2nd edition the Film Noir eBook by Paul Duncan from eBooks.com. An excerpt:

The usual relationship in a Film Noir is that the male character (private eye, cop, journalist, government agent, war veteran, criminal, lowlife) has a choice between two women: the beautiful and the dutiful.The dutiful woman is pretty, reliable, always there for him, in love with him, responsible “all the things any real man would dream about. The beautiful woman is the femme fatale, who is gorgeous, unreliable, never there for him, not in love with him, irresponsible “all the things a man needs to get him excited about a woman. The Film Noir follows our hero as he makes his choice, or his choice is made for him. The reason the femme fatale meets the male character is because she has already made her choice. She is usually involved with an older, very powerful man (gangster, politician, millionaire), and she is looking to make some money from the relationship. She needs a smart man (who is also dumber than her) to go get that money, and take the fall if things go wrong. Enter the male character. The story follows the romantic/erotic foreplay of their relationship. The male character is often physically and mentally abused in this meeting and separating of bodies. Sometimes, he ends up doing very bad things. What is most surprising about Film Noir, and the reason I suspect it has become so difficult to categorise and pigeonhole, is that the focus of the films can be from the point of view of any of the characters caught in this relationship. For example, we can follow the femme fatal’s story or, as is more often the case, the dutiful woman’s. (The timid, unknowing woman who learns about the dark side of life harks back to the Gothic novel of the nineteenth century, which is where Noir Fiction came from.) This is because all the characters are equally interesting “they are all either obsessed with something they desire (money, power, sex), or compelled to do what they do because of their nature, or the physical or social environment they live in. The Film Noir follows a number of discernible frameworks within which the characters clash and collide. To show the workings of the police and government agencies, we had the Documentary Noir. Many filmmakers worked with army documentary units during World War Two, and discovered the freedom of movement the new, lightweight cameras afforded them. Audiences back home also got used to seeing them, so they found it easier to accept the rough style when it was presented to them as a feature film.The Docu Noir invariably had an authoritative voice telling us the facts (time, place, purpose) of the case, and we followed the investigation through to the end.The first one was The House on 92nd Street (1945) directed by Henry Hathaway, who did several in this style. Others of note include Call Northside 777 (1948), The Naked City (1948) (which spawned a TV series), Joseph H Lewis’ The Undercover Man (1949) and The Enforcer (1951). In the 50s, this style was subverted and reinvented by Alfred Hitchcock in his magnificent The Wrong Man (1956). In this film, instead of glorifying the law, we see a man and his family becoming victims of the police procedure – in the end his wife has a mental breakdown.

In the paranoid 1950’s, Dashiell Hammett was jailed under sinister manipulation of The Smith Act. Popular radio serials based on Hammett’s books, including The Maltese Falcon, were immediately cancelled, and his books withdrawn from publication in the US.

When he was released from prison the IRS, attached his income and the copyright on his books and stories for payment of back taxes and penalties. He was broke and unpublishable.

Hammett died in 1961. Two years later friend, fellow writer and progressive, Lillian Hellman, bought back the copyrights to his works at an IRS auction for US$5,000.

In 1998, the Editorial Board of The Modern Library named The Maltese Falcon as one of the 100 best novels in English of the 20th century.

In 2005, the US Senate approved a resolution commemorating the 75th anniversary of The Maltese Falcon and recognising it as a great American crime novel.

A post today on the Monochrom.Blog lead me to an excellent article by Chris Fujiwara on this topic in his review, in the Boston Globe on 15 January 2006, of the book, The Philosophy of Film Noir (2006), a collection of essays from the University of Kentucky Press that explores the philosophical underpinnings of movies from the classic noir period and after.

Chris Fujiwara, a writer living in Chelsea, is the author of, Jacques Tourneau: The Cinema of Nightfall (Johns Hopkins University Press), and was working on a critical biography of Otto Preminger at the time he wrote the article.

I have not read The Philosophy of Film Noir, and my post of June 20, The Big Heat: Film Noir As Social Criticism, is purely coincidental, but Fujiwara’s discussion of the influence of Eureopean extistentialism on American noir in the the 40s and 50s is supportive of the views expressed in my post. I recommend the full article to you, and offer these highlights:

The philosophy of noir has also been linked to the European literary and philosophical movement known as Existentialism, though frequently when commentators use that term, it’s less with the writings of Sartre and Camus in mind than as a stand-in for ideas like ”absurdity” and ”alienation.” In an essay portentously called ”Film Noir and the Meaning of Life,” his contribution to ”The Philosophy of Film Noir,” Steven M. Sanders, an emeritus professor of philosophy at Bridgewater State College in Massachusetts, claims that ”the thread running through the design of film noir is the sense that life is meaningless.” Noir, Conard writes, is nothing less than ”a sensibility or worldview that results from the death of God.”…

This kind of analysis isn’t new, but it highlights something that isn’t always discussed about noir: That the genre, which evokes such quintessentially American icons as Bogart and a shadow-filled Los Angeles, actually finds its roots in Europe… [my emphasis]

As ”The Philosophy of Noir” reminds us, during its peak era, noir was the form that imported ”European” alienation, doubt, and dread into the framework of the American crime film.

I should also acknowledge in this post the comment from Lloydville of mardecortesbaja.com to my June 20 post:

You make a good point… film noir definitely derived in part from European existentialism . . . but existentialism itself was influenced by Poe, via Baudelaire, so the lines of connection are complex.

We can’t see film noir as simply a European product, an import, because it was so wildly popular with the American public, which must reflect an existential malaise that did reach North America after WWII, aroused by the horrific spectacle of the conflict and by the atomic bomb. It reflected a subconscious dread deeply rooted in the American psyche.

Appropriately, Fujiwara concludes his article by saying: As always, however, the definition of noir itself remains in the shadows.

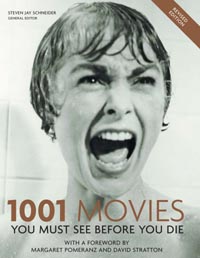

I have been going through the first edition of 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die (2003 New Burlington Books), and highly recommend it to film noir fans. All the major noirs are included, and the commentaries are fresh and incisive.