And I see you now, you woman of that night – I see you in the sanctity of some dirty harbor bedroom flop-joint, with the mist outside, and you lying with legs loose and cold from the fog’s lethal kisses, and hair smelling of blood, sweet as blood, your frayed and ripped hose hanging from a rickety chair beneath the cold yellow light of a single, spotted bulb, the odor of dust and wet leather spinning about, your tattered blue shoes tumbled sadly at the bedside, your face lined with the tiring misery of Woolworth defloration and exhausting poverty, your lips slutty, yet soft blue lips of beauty calling me to come come come to that miserable room and feast myself upon the decaying rapture of your form, that I might give you a twisting beauty for misery and a twisting beauty for cheapness, my beauty for yours, the light becoming blackness as we scream, our miserable love and farewell to the tortuous flickering of a gray dawn that refused to really begin and would never really have an ending.

John Fante – The Road to Los Angeles (1933)

Category: Books

Re-Focusing Film Noir

After some recent reading on film noir, I am re-focusing my approach to film noir, and this re-appraisal will influence my coming film noir reviews.

If we go back to the hard-boiled detective novels of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler, we find protagonists who are essentially outsiders with personas concerned not with redemption but with maintaining a stasis that is outside the mainstream in an existential sense. Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe are not concerned with money or status, conventional relationships, or necessarily following the letter of the law. These guys are loners. Independent men above banal striving and ambition, but loyal to a code that not only guides but defines them. While the PI works at the perimeter of convention, his realm goes beyond the dark sordid recesses of criminality to the rotten core of polite society. Death-in-life is their métier, and integrity their salvation. But this integrity and independence casts them adrift. They are of society but not anchored in it. Their alienation is knowing and desperate: capitulation is existential death. These guys are subversives as film noir is subversive: a losing battle against chaos. Nietzche was wrong: superman is a ‘loser’. The loser is outside society, his alienation is a positive reverse-psychosis, he maintains his sanity in a crazy urban nightmare only by his detachment, yet he despairs of it. Ambivalence and entrapment the cost.

L.A. 1939: Ask the dust

Max Yavno (Los Angeles: Underneath Third Avenue El – 1938)

I am currently reading a very interesting book, Unless the Threat of Death Is Behind Them: Hard-Boiled Fiction and Film Noir (2006 The Johns Hopkins University Press) by John T. Irwin, which studies five novels and the films based on them – The Maltese Falcon, The Big Sleep, Double Indemnity, High Sierra, and Night Has a Thousand Eyes. Irwin’s thesis seems to be that noir is concerned with death metaphysically as life-in-being and death also in an existential sense bred of social alienation. The following excerpts for me express the kind of prose Irwin is concerned with, and are passages from my own reading that have particularly struck me as being relevant.

“I went up to my room, up the dusty stairs of Bunker Hill, past the soot-covered frame buildings along that dark street, sand and oil and grease choking the futile palm trees standing like dying prisoners, chained to a little plot of ground with black pavement hiding their feet. Dust and old buildings and old people sitting at windows, old people tottering out of doors, old people moving painfully along the dark street. The old folk from Indiana and Iowa and Illinois, from Boston and Kansas City and Des Moines, they sold their homes and their stores, and they came here by train and by automobile to the land of sunshine, to die in the sun, with just enough money to live until the sun killed them, tore themselves out by the roots in their last days, deserted the smug prosperity of Kansas City and Chicago and Peoria to find a place in the sun. And when they got here they found that other and greater thieves had already taken possession, that even the sun belonged to the others; Smith and Jones and Parker, druggist, banker, baker, dust of Chicago and Cincinnati and Cleveland on their shoes, doomed to die in the sun, a few dollars in the bank, enough to subscribe to the Los Angeles Times, enough to keep alive the illusion that this was paradise, that their little papier-mache homes were castles. The uprooted ones, the empty sad folks, the old and the young folks, the folks from back home. These were my countrymen, these were the new Californians. With their bright polo shirts and sunglasses, they were in paradise, they belonged. But down on Main Street, down on Towne and San Pedro, and for a mile on lower Fifth Street were the tens of thousands of others; they couldn’t afford sunglasses or a four-bit polo shirt and they hid in the alleys by day and slunk off to flop houses by night. A cop won’t pick you up for vagrancy in Los Angeles if you wear a fancy polo shirt and a pair of sunglasses. But if there is dust on your shoes and that sweater you wear is thick like the sweaters they wear in the snow countries, he’ll grab you. So get yourselves a polo shirt boys, and a pair of sunglasses, and white shoes, if you can. Be collegiate. It’ll get you anyway. After a while, after big doses of the Times and the Examiner, you too will whoop it up for the sunny south. You’ll eat hamburgers year after year and live in dusty, vermin-infested apartments and hotels, but every morning you’ll see the mighty sun, the eternal blue of the sky, and the streets will be full of sleek women you never will possess, and the hot semi-tropical nights will reek of romance, you’ll never have, but you’ll still be in paradise, boys, in the land of sunshine.”

– John Fante, Ask the Dust (1939)

“No feelings at all was exactly right. I was as hollow and empty as the spaces between the stars. . . . Out there in the night of a thousand crimes people were dying, being maimed, cut by flying glass, crushed against steering wheels or under heavy tires. People were being beaten, robbed, strangled, raped, and murdered. People were hungry, sick; bored, desperate with loneliness or remorse or fear, angry, cruel, feverish, shaken by sobs. A city no worse than others, a city rich and vigorous and full of pride, a city lost and beaten and full of emptiness. It all depends on where you sit and what your own private score is. I didn’t have one. I didn’t care.”

– Raymond Chandler, The Big Sleep (1939)

Huzzah!! NOIR: An exciting new graphic novel project

©2009 I.N.J. Culbard. Used with Permission.

A group of nine very talented graphic artists/writers have launched an exciting new blog project titled Huzzah!! NOIR.

Each contributor in turn will be contributing a page that develops the story of a washed-up 40s boxer searching for a dame in a dark noir metropolis. Shades of Murder, My Sweet?

So far four pages are up with stunning noir graphics and a promising pulp noir story-line.

“The B List” in Paperback

The B List: The low-budget beauties, genre-bending mavericks, and cult classics we love (Da Capo Press. $15.95. 288 pages), edited by David Sterritt and John Anderson, has been released as a paperback. The book is organised by genre – film noir, road movies, horror movies etc. Contributors include the Village Voice’s J. Hoberman, Newsweek magazine’s David Ansen, Salon’s Stephanie Zacharek, Roger Ebert and others.

The Noir section is fairly predictable, though The Well (1951) is a new one for me. I see King Greole (1958) is included under a rock movies section, though it could also be seen as having noir elements, and for me is Elvis Presley’s best movie (I am a closet Elvis fan).

You can check out the contents in full at Amazon.

Sci-Fi Noir: New Book

A new book Tech-Noir: The Fusion of Science Fiction and Film Noir by Paul Meehan has been published.

The publishers description:

This critical study traces the common origins of film noir and science fiction films, identifying the many instances in which the two have merged to form a distinctive subgenre known as Tech-Noir. From the German Expressionist cinema of the late 1920s to the present-day cyberpunk movement, the book examines more than 100 films in which the common noir elements of crime, mystery, surrealism, and human perversity intersect with the high technology of science fiction. The author also details the hybrid subgenre’s considerable influences on contemporary music, fashion, and culture.

The book has received a favorable review from film writer John Muir.

Noir City 2009 Program

Thanks to Dark Cty Dame for advance details of the program for NOIR CITY 7, the 2009 San Francisco Film Noir Festival, to be held January 23–February 1, 2009, at the Castro Theatre, and which will have a newspaper theme:

Friday, January 23

Deadline USA (1952)

Scandal Sheet (1952)

Saturday, January 24

Matinee:

Chicago Deadline (1949)

Blind Spot (1947)

Evening show (with Arlene Dahl):

Slightly Scarlet (1956)

Wicked as They Come (1956)

Sunday, January 25

Ace in the Hole (1951)

Cry of the Hunted (1953)

Monday, January 26

Alias Nick Beal (1949)

Night Editor (1946)

Tuesday, January 27

The Harder They Fall (1956)

Johnny Stool Pigeon (1949)

Wednesday, January 28

While the City Sleeps (1956)

Shakedown (1950)

Thursday, January 29

The Big Clock (1948)

Strange Triangle (1946)

Friday, January 30

The Unsuspected (1947)

Desperate (1947)

Saturday, January 31

Matinee:

Two O’Clock Courage (1945)

Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956)

Evening show:

One False Move (1992)

Sunday, February 1

Shock Corridor (1963)

The Killers (1946) (newly restored)

Full details to be announced.

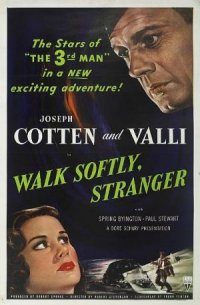

Walk Softly, Stranger (1950): Romantic Noir

A gambler on the skids pulls a heist as a final gambit after adopting

a false identity in a small town and falling for a rich crippled woman

(1948 RKO. Directed by Robert Stevenson 81 mins)

Cinematography by noir veteran Harry J. Wild

Screenplay by Manuel Seff and Paul Yawitz (adaptation of play by Frank Fenton)

Art Direction by RKO stalwart Albert S. D’Agostino, and Alfred Herman

Starring Joseph Cotten and Alida Valli

Although Walk Softly, Stranger was made before The Third Man (1949), its release was said to have been held off until after The Third Man to leverage the star appeal of Joseph Cotten and Alida Valli. But the movie was panned by very faint praise from Bosley Crowther in his New York Times review on the film’s release, and is a sleeper.

I have always had a soft spot for Joseph Cotten, the modest everyman with unflinching decency and incredible loyalty, and I always fall in love with Alida Valli, Italy’s sensuous incarnation of Ingrid Bergman. Both these actors bring depth to this essentially b-romance with a noir arc, and Spring Byington is superb as the landlady who takes Cotten under her wing. The story is unusual enough to sustain interest until the climax, which is brief but effective. The script is literate and elegant, while also peppered with witty throwaway lines. There is a beautifully sardonic scene on the cusp of the climax with a car crashing into a billboard displaying a pointed advert.

The theme of the past catching up with noir protagonist is integral to the resolution, and Cotten toughens his persona credibly when he has to deal with an accomplice on-the-run and in confronting his pursuers. When he brutally punches his accomplice it is truly shocking, as such a violent reaction is at odds with his sincere affection for his landlady and poetic romancing of Valli.

This is a slow-moving noir with a hint of the classic women’s picture in the wooing and in the final redemptive scene, but rewards you with an honest story and memorable characters.

If you want dark dames and city streets menaced by violence, look elsewhere.

The Tortured Psyche of Cornell Woolrich

The most prolific noir novelist during the classic film noir cycle was Cornell Woolrich. From Convicted (1938) to No Man of Her Own (1950) 15 of his stories were adapted for the screen. Woolrich’s tales were darkly paranoid and played out in a brutally malign universe filled with existential dread and entrapment.

His nihilism was deeply personal. A repressed loner he died a lonely death in 1968 at the age of 65. After his death, a telling literary fragment was found in his personal papers:

I was only trying to cheat death… I was only trying to surmount for a while the darkness that all my life I surely knew was going to come rolling in on me one day and obliterate me. I was only trying to stay alive a little brief while longer, after I was already gone. To stay in the light, to be with the living, a little while past my time.

Woolrich’s writing was not in the hard-boiled tradition, but intensely descriptive and, you could say, richly cinematic:

We went down a new alley… ribbons of light spoked across this one, glimmering through the interstices of an unfurled bamboo blind stretched across an entryway. The bars of light made cicatrices across us. He reached in at the side and slated up one edge of the pliable blind, made a little tent-shaped gap. For a second I stood alone, livid weals striping me from head to foot.

– From Woolrich’s 1944 novel The Black Path of Fear, which was made into the film The Chase in 1946.

These are the major noirs based on Woolrich’s novels and short stories:

Street of Chance (1942) – based on the novel titled The Black Curtain

The Mark of the Whistler (1944) – based on the short story Dormant Account

The Leopard Man (1943) – based on the novel Black Alibi

Phantom Lady (1944)

Deadline at Dawn (1946)

Black Angel (1946)

The Chase (1946) – based on the novel The Black Path of Fear

Fall Guy (1947) – based on the short story C-Jag

Fear in the Night (1947) – based on the short story And So to Death (Nightmare)

The Guilty (1947) – based on the short story He Looked Like Murder

I Wouldn’t Be in Your Shoes (1948)

Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1948)

The Window (1949) – based on the short story The Boy Cried Murder

Convicted (1950) – based on the novel Face Work

No Man of Her Own (1950) – based on the novel I Married a Dead Man

Nightmare (1956) – based on the short story And So to Death (Nightmare)

The Bride Wore Black (France 1968)

Reference:

Geoff Mayer and Brian McDonnell, Encyclopedia of Film Noir (Greenwood Press 2007)

Noir Novelists

Elsewhere I recently became embroiled in a discussion where a reviewer of a film noir who had not the read the novel was admonished for not crediting the significant contribution of the writer of the original novel.

This has spurred me to put together a list of the major “noir” novelists whose works underpinned the genesis and flowering of film noir in the 1940s and 1950s.

The list is not exhaustive and features works that were adapted for the screen in notable films noir.

A.I. Bezzerides 1908-2007

They Drive by Night (1940) – screenplay of his novel Long Haul

Desert Fury (1947) – co-wrote screenplay of Ramona Stewart novel Desert Town

Thieves’ Highway (1949) – screenplay of his novel Thieves Market

On Dangerous Ground (1952) – screenplay of the novel “Mad with Much Heart” by Gerald Butler

Kiss Me Deadly (1955) – screenplay of Mickey Spillane novel

W. R. Burnett (1899–1982)

Little Caesar (1931)

High Sierra (1941)

Nobody Lives Forever (1946)

The Asphalt Jungle (1950)

James M. Cain (1892–1977)

Double Indemnity (1944)

Mildred Pierce (1945)

The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946)

Raymond Chandler (1888–1959)

Time to Kill (1942) – based on the novel The High Window

Double Indemnity (1944) – co-scripted screenplay based on the James M. Cain novel

The Big Sleep (1946)

The Blue Dahlia (1946) – original screenplay

Farewell, My Lovely (aka Murder, My Sweet) (1944)

The Brasher Doubloon (1947) – based on the novel The High Window

Lady in The Lake (1947)

Strangers on a Train (1951) – original screenplay

Playback (1949) – un-produced screenplay

Playback (1959) – novelisation of un-produced screenplay

The Long Goodbye (1973)

Steve Fisher (1912–1980)

I Wake Up Screaming (1941)

Johnny Angel (1945) – original screenplay

Lady in the Lake (1947) – original screenplay

Roadblock (1951) – original screenplay

City That Never Sleeps (1953) – original screenplay

36 Hours (1953) – original screenplay

David Goodis (1917–1967)

Dark Passage (1946)

The Unfaithful (1947) – original screenplay

Nightfall (1957)

The Burglar (1953)

Shoot the Piano Player (1960) – based on the novel Down There

Dashiell Hammett (1894–1961)

The Glass Key (1935)

The Maltese Falcon (1941)

The Glass Key (1942)

Jonathan Latimer (1906–1983)

The Glass Key (1942) – original screenplay

Nocturne (1946)

They Won’t Believe Me (1947)

The Big Clock (1948) – screenplay based on the Kenneth Fearing novel

Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1948) – screenplay based on the Cornell Woolrich novel

The Unholy Wife (1957)

Horace McCoy (1897–1955)

Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye (1950)

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969)

William P. McGivern (1918-1982)

The Big Heat (1953) – based on Saturday Evening Post serial

Shield for Murder (1954)

Rogue Cop (1954)

Odds Against Tomorrow (1959)

Cornell Woolrich (1903–1968)

Street of Chance (1942) – based on the novel titled The Black Curtain

The Mark of the Whistler (1944) – based on the short story Dormant Account

The Leopard Man (1943) – based on the novel Black Alibi

Phantom Lady (1944)

Deadline at Dawn (1946)

Black Angel (1946)

The Chase (1946) – based on the novel The Black Path of Fear

Fall Guy (1947) – based on the short story C-Jag

Fear in the Night (1947) – based on the short story And So to Death (Nightmare)

The Guilty (1947) – based on the short story He Looked Like Murder

I Wouldn’t Be in Your Shoes (1948)

Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1948)

The Window (1949) – based on the short story The Boy Cried Murder

Convicted (1950) – based on the novel Face Work

No Man of Her Own (1950) – based on the novel I Married a Dead Man

Nightmare (1956) – based on the short story And So to Death (Nightmare)

The Bride Wore Black (France 1968)