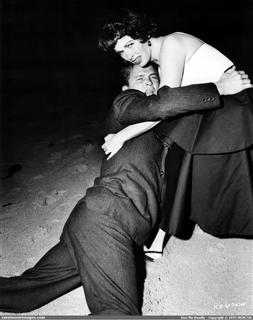

The conventional wisdom is that Mike Hammer as portrayed in Kiss Me Deadly is irredeemably bad.

For instance, we have Glenn Erickson in a recent article for the blog, Noir Of The Week :

Robert Aldrich and screenwriter A.I. Bezzerides’ film was heralded as an extreme expression of protest against 1950s conformist complacency. It subverted Spillane by criticizing his brutal avenger Mike Hammer as greedy, narcissistic and infantile.

And from the IMDB page for the movie:

Kiss Me Deadly is the definitive sleazy detective movie… Mickey Spillane’s sadistic private eye Mike Hammer, turned from successful private eye to sleazy bedroom dick, is the quintessential anti-hero, doing just about anything and everything wrong to get a piece of the pie that the characters call ‘The Big What’s-it’.

Have you ever you had the feeling after reading a review or critique of a film you have seen, that the writer has seen a different movie? This is how I feel about these commentaries.

The Ralph Meeker character, was a sleazy PI, but after his encounter with Christina, and his near-death at the hands of her killers, he is a changed man. Is it so strange that he wants to hunt down those who tried to kill him? Is he driven solely by his need to track down the The Big What’s-it? Or maybe he is haunted by Christina’s admonition to not forget her? So he slaps around a couple of guys, snaps a vinyl record, and crushes the hand of the creep at the morgue? Is he any more immoral than the Feds? Gimme a break.