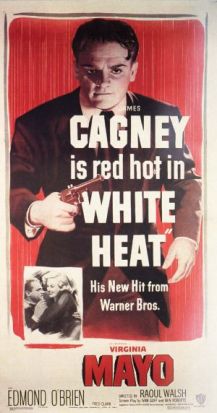

Story of a psychotic hood with an Oedipus complex

(1949 Warner Bros. Directed by Raoul Walsh 114 mins)

Cinematography by Sid Hickox

Screenplay by Ivan Goff and Ben Roberts from a story by Virginia Kellogg

Original Music by Max Steiner

Art Direction by Edward Carrere

Starring:

James Cagney – Arthur ‘Cody’ Jarrett

Virginia Mayo – Verna Jarrett

Edmond O’Brien – Vic Pardo – alias for undecover cop Fallon

Margaret Wycherly – Ma Jarrett

Film Noir Filmographies:

Raoul Walsh: They Drive by Night (1940), High Sierra (1941)

Sid Hickox: To Have and Have Not (1944), The Big Sleep (1946), Possessed (1947),

Dark Passage (1947)

Virginia Kellogg: T-Men (1947) (story), Caged (1950) (screenplay)

Edward Carrere: Dial M for Murder (1954), I Died a Thousand Times (1955),

Sweet Smell of Success (1957)

“White Heat = Scarface + Psycho” – Time Out

“The most gruesome aggregation of brutalities ever presented under the guise of entertainment” – Cue

“In the hurtling tabloid tradition of the gangster movies of the thirties, but its matter-of-fact violence is a new post-war style” – Time

“a wild and exciting picture of mayhem and madness” – Life

“an incendiary performance by James Cagney” – The Rough Guide to Film Noir

“Cagney is an epileptic and a borderline psychotic, and the cinema has rarely gone this for in a description of a true Oedipus” – A Panorama of American Film Noir (1955)

“Cagney… seems to incarnate the unstable explosive energies set loose by atomic fission” – Andrew Spicer in Film Noir

“A tragic grandeur… is achieved and culminates in Cody’s delirious and explosive self-immolation atop a metallic pyre” – Film Noir: An Encyclopaedic Reference

From the daring and brutally violent train robbery that opens the film, this gangster flick has a relentless trajectory that ends only with the incendiary finale-de-resistance. Director, Raoul Walsh, and cinematographer, Sid Hickox, have produced one of the tautest and most electric thrillers ever to emanate from Hollywood, which together with the nuanced screenplay, has the spectator strapped into an emotional strait-jacket that is released only in the final explosive frames.

Jimmy Cagney as the criminal psychotic Cody Jarrett dominates the screen in a bravura performance that is as dynamic as it is intense. Edmond O’Brien as the undercover cop Fallon, is no match for Cagney, and appears flat and almost irrelevant. Cody’s razor-sharp intelligence, and unflinching decisiveness and brutality propel the action – Fallon and the other cops can only follow in his wake. Virginia Mayo is well-cast as Cody’s slatternly wife, and is as cheap and conniving as any gangster’s mole before or since. Only Ma Jarrett matches her in evil guile.

The film-making team conspires to hold you not only in awe of Cody but also to perversely empathize with him. Strange to say he is the only genuine character in the motley crew organised for the final disastrous heist. Even Fallon comes off looking lifeless and less than honorable. The mise-en-scene is calculated to subvert your moral compass. Cody is decisive and acts without hesitation or qualm, while Fallon’s actions are reactive and ponderous. When Fallon tries to sneak out of the gang’s hide-out on the eve of the heist to alert his superiors, he is way-laid and has to concoct a story about wanting to hook-up with his ‘wife’ for the night, as Cody talks intimately and almost poetically to him of his grief for his dead mother, and how he was just ‘talking’ to her when wandering in the brush outside.

In the final shoot-out Cody is pinned atop a gas storage silo at an LA refinery, while Fallon from a safe distance takes pot-shots at him with a sniper’s rifle. Cody won’t go down, and only when he wildly shoots his pistol into the silo is his fate finally sealed. Fallon looks far less heroic…