Director: Billy Wilder

Screenplay: Charles Brackett, Billy Wilder and D.M. Marshman Jr

Cinematography: John F. Seitz

Editing: Arthur Schmidt

Art Direction: Hans Dreier and John Meehan

Music: Franz Waxman

Cast: William Holden (Joe Gillis), Gloria Swanson (Norma Desmond),

Erich von Stroheim (Max von Mayerling), Nancy Olson (Betty Schaefer)

Paramount 1950 (110 min)

“Wilder grasped that Hollywood itself could be a scene of Gothic isolation and solipsistic emotion. He showed the grandeur that could emerge from the parasitical relations between actors and writers, performers and directors, stars and star-gazers – cannibals all. Like most noir films, with their dark motives and circular structures, Sunset Boulevard makes corruption and betrayal seem inescapable. Yet Wilder pays tribute to what can emerge from this hothouse world, just as he does honor to the film formulas he lightly parodies. As Hollywood keeps reinventing itself, as Wilder’s own films become relics of a distant age, his barbed tribute stings and sings with even more authority.”

– Morris Dickstein, The A List (Da Capo Press).

“… a tale of humiliation, exploitation, and dashed dreams… The performances are suitably sordid, the direction precise, the camerawork appropriately noir, and the memorably sour script sounds bitter-sweet echoes of the Golden Age of Tinseltown… It’s all deliriously dark and nightmarish, its only shortcoming being its cynical lack of faith in humanity: only von Stroheim, superb as Swanson’s devotedly watchful butler Max, manages to make us feel the tragedy on view.” – Time Out

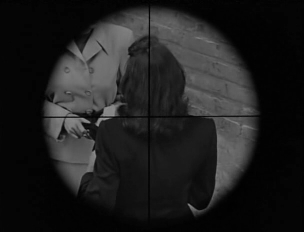

Sunset Boulevard is a masterpiece. Billy Wilder’s assured direction and the elegant and fluid camera of veteran cinematographer John F. Seitz enthrall from the first frame to the last. A literate script, great performances from the lead actors, an expressionistic score from Franz Waxman, and the bravado art direction of Hans Dreier and John Meehan define a deeply focused journey into dissolution and madness. There is also a wit and wry humor that lightens the mood before the noir universe begins to exact its vengeance on the poor souls who stumble in their struggle to simply live and love.

The last major Hollywood film shot on a nitrate negative, the restored DVD version of 2002 reproduces the “lustrous black and white images” cinema audiences experienced on the film’s release nearly 60 years, and gives the drama an immediacy that belies the many years that have passed.

Applauded as the quintessential movie about Hollywood, for the writer the theme of the film is deeper and more universal. Aging silent actress Norma Desmond, who hasn’t worked for 20 years, lives out the autumn of her life in a decaying 1920s palace on Sunset Blvd. with her intensely loyal factotum, Max, in gothic delusional grandeur, dreaming of the day she returns to the studio where Cecil B. DeMille will direct her abominable screenplay of Salome, in which of course she will play the lead. Into this scenario stumbles a younger man, Joe Gillis, a screenwriter on the skids and on the lam from his creditors. She wants her script edited and he is desperate for money and lodgings – a bargain is made in perdition.

He becomes her kept lover and she falls madly in love with him. He tries to rebel, she slashes her wrists, and he runs back to the mansion-cum-prison where only the front cell-like gate has a lock. His thwarted ambition, lassitude, weakness, and a kind of reciprocated love for the aging siren, hold him to her, until he starts sneaking out at night to work on a script with Betty, a young studio reader, who falls in love with him. Norma finds out, and one whispered surreptitious phone call has thunderous consequences for all.

In the quote at the head of this review, the Time Out writer says the movie’s “only shortcoming… [is] its cynical lack of faith in humanity: only von Stroheim, superb as Swanson’s devotedly watchful butler Max, manages to make us feel the tragedy on view.” I can’t agree with this assessment. Gloria Swanson, William Holden, and Erich von Stroheim inhabit their roles with an intense humanity, and Nancy Olson as Betty is totally engaging as a young woman with heart and a vivacious intelligence. Norma’s femininity and vulnerability are on display in every scene. Her tragedy is that of the successful woman whose career is side-lined into a banal existence of domestic isolation: her angst is palpable and exquisite. Max, the loyal friend, ex-husband, and faithful retainer, idolises Norma, and his noble intentions in perpetuating Norma’s delusions tragically precipitate her destruction. Joe is desperate when he enters his Faustian-pact with Norma, and his actions are all too human. His first attempt at freedom is thwarted by his ‘love’ for Norma, and his capitulation is not totally abject. His second and final renunciation is as noble and self-less as it is tragic.

Wilder has fashioned a deeply sympathetic story of four fundamentally decent people, each tortured in their own way, and each sadly complicit in the inevitable doom that will engulf them.