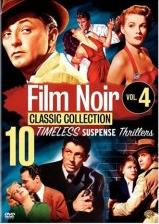

On July 31, Warner Home Video, will release Film Noir Classic Collection, Vol. 4, which contains a bumper 10 remastered movies on five double DVDs from the classic film noir period of the 40s and 50s:

Act of Violence / Mystery Street

Crime Wave / Decoy

Illegal / The Big Steal

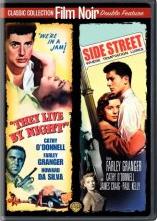

They Live By Night / Side Street

Where Danger Lives / Tension

Each DVD in the set can be purchased separately.

The DVD release has reviewed by Glenn Erickson of DVDTalk.Com, with a focus on They Live By Night and Side Street.

Update 7 Aug 2007: Decoy has been has been reviewed on Noir Of the Week.

Update 8 Aug 2007: All movies on the DVD are reviewed in filmjournal.net by clydefro.

Update 9 Aug 2007: All movies on the DVD are reviewed by Adnan Tezer at dvd.monstersandcritics.com.

Update 13 Aug 2007: All movies on the DVD are reviewed by dvdverdict.com.

Update 14 Aug 2007: All movies on the DVD are reviewed by The Shelf DVD Reviews.

Update 21 Aug 2007: All movies on the DVD are reviewed by Film Forno.

Update 9 Sep 2007: An interesting review of the DVD and film noir generally by Cullen Gallagher of The Brooklyn Rail.

These movies are a feast for noir fans with many of the top-level directors and stars of the period featured:

Act of Violence (1948)

Cast: Van Heflin, Robert Ryan, Janet Leigh, Mary Astor, Phyllis Thaxter

Director: Fred Zinnemann

War veteran Frank Enley seems to be a happily married small-town citizen until he realises Joe Parkson is in town. It seems Parkson is out for revenge because of something that happened in a German POW camp, and when a frightened Enley suddenly leaves for a convention in L.A., Parkson is close behind.

Mystery Street (1950)

Cast: Ricardo Montalban, Sally Forrest, Bruce Bennett, Elsa Lanchester, Marshall Thompson

Director: John Sturges

Vivian, a B-girl working at “The Grass Skirt,” is being brushed off by her rich, married boyfriend. To confront him, she hijacks drunken customer Henry Shanway and his car from Boston to Cape Cod, where she strands Henry…and is never seen again. Months later, a skeleton is found (sans clothes or clues) on a lonely Cape Cod beach. Using the macabre expertise of Harvard forensic specialist Dr. McAdoo, Lt. Pete Morales must work back from bones to the victim’s identity, history, and killer. Will he succeed in time to save an innocent suspect?

Crime Wave (1954)

Cast: Sterling Hayden, Gene Nelson, Phyllis Kirk, Ted de Corsia, Charles Bronson

Director: André De Toth

Three San Quentin escapees kill a cop in a gas-station holdup. Wounded, Morgan flees through black-shadowed streets to the handiest refuge: with former cellmate Steve Lacey, who’s paroled, with a new life and lovely wife, and can’t afford to be caught associating with old cronies. But homicide detective Sims wants to use Steve to help him catch Penny and Hastings, who in turn extort his help in a bank job. Is there no way out for Steve?

Decoy (1946)

Cast: Jean Gillie, Edward Norris, Robert Armstrong, Herbert Rudley, Sheldon Leonard

Director: Jack Bernhard

Gangster Frank Olins (Robert Armstrong) is to die in the gas chamber much to the dismay of his girlfriend Margot Shelby (Jean Gillie) as he is carrying the secret of the location of $400,000 with him. Margot seduces gangster Jim Vincent (Edward Norris) to get him to engineer the removal of Olins’ body from the prison immediately after he dies in the gas chamber. She takes prison doctor Craig (Herbert Rudley) away from his nurse/girl friend (Marjorie Woodworth) and gets him to administer an antidote for cyanide gas poisoning. During the removal of Olins’ body, the hearse driver is killed by Tommy (Phil Van Zandt). The revived Olins gives Margot half of a map showing the money location and Vincent, in a fit of jealousy, kills Olins and takes the other half. Because the doctor’s plates on his car will get them through the police roadblocks, Vincent and Margot take him with them on the money hunt.

Illegal (1955)

Cast: Edward G. Robinson, Nina Foch, Hugh Marlowe, Robert Ellenstein, DeForest Kelley

Director: Lewis Allen

Ambitious D.A. Victor Scott zealously prosecutes Ed Clary for a woman’s murder. But as Clary walks “the last mile” to the electric chair, Scott receives evidence that exonerates the condemned man. Realizing that he’s made a terrible mistake he tries to stop the execution but is too late. Humbled by his grievous misjudgement, Scott resigns as a prosecutor. Entering private practice, he employs the same cunning that made his reputation and draws the attention of mob kingpin, Frank Garland. The mobster succeeds in bribing Scott into representing one of his stooges on a murder rap and Scott, in a grand display of courtroom theatrics, wins the case. But soon Scott finds himself embroiled in dirty mob politics. The situation becomes intolerable when his former protégé in the D.A.’s office is charged with a murder that seems to implicate her as an informant to the Garland mob. Can Victor defend the woman he secretly loves and also keep his life?

The Big Steal (1949)

Cast: Robert Mitchum, Jane Greer, William Bendix, Patrick Knowles, Ramon Novarro

Director: Don Siegel

Jane and Duke (alias Capt. Blake) accidentally meet in Vera Cruz while chasing flim-flam man Fiske. Soon the local Inspector General (El Gato) is involved. Fiske races across Mexico, pursued by Jane and Duke, trailed by the real Capt. Blake. The crafty Inspector General is waiting for them in Tihuacan but they all give him the slip, just in time for the climactic finale. Very tight script and pacing.

They Live by Night (1948

Cast: Farley Granger, Cathy O’Donnell, Howard Da Silva, Jay C. Flippen, Helen Craig

Director: Nicholas Ray

In the ’30s, three prisoners flee from a state prison farm in Mississippi. Among them is 23-yo Bowie, who spent the last seven years in prison and now hopes to be able to prove his innocence or retire to a home in the mountains and live in peace together with his new love, Kitty. But his criminal companions persuade him to participate in several heists, and soon the police believe him to be their leader and go after “Bowie the Kid” harder than ever.

Side Street (1950)

Cast: Farley Granger, Cathy O’Donnell, James Craig, Paul Kelly, Jean Hagen

Director: Anthony Mann

Joe Norson, a poor letter carrier with a sweet, pregnant wife, yields to momentary temptation and steals $30,000 belonging to a pair of ruthless blackmailers who won’t stop at murder. After a few days of soul-searching, Joe offers to return the money, only to find that the “friend” he left it with has absconded. Now every move Joe makes plunges him deeper into trouble, as he’s pursued and pursuing through the shadowy, sinister side of New York.

Where Danger Lives (1950)

Cast: Robert Mitchum, Faith Domergue, Claude Rains, Maureen O’Sullivan, Charles Kemper

Director: John Farrow

One night at the hospital, young doctor Jeff Cameron meets Margo, who’s brought in after a suicide attempt. He quickly falls for her and they become romantically involved, but it turns out that Margo is married. At a confrontation, Margo’s husband accidentally gets killed and Jeff and Margo flee. Heading for Mexico, they try to outrun the law.

Tension (1950)

Cast: Richard Basehart, Audrey Totter, Cyd Charisse, Barry Sullivan, Lloyd Gough

Director: John Berry

A mousy drugstore manager turns killer after his conniving wife leaves him for another man. He devises a complex plan, which involves assuming a new identity, to make it look like someone else murdered her new boyfriend. Things take an unexpected turn when someone else commits the murder first and he becomes the prime suspect.