There is a certain irony in this excerpt from the novel by Italo-American Pietro Di Donato, Christ in Concrete (1939), a story of Italian immigrant building workers and their families in Brooklyn during the Depression. In 1949 a film adaptation of the novel by director Edward Dmytryk, featured teeming tenements and residential streets shot with a provocatively gritty realism and film noir atmospherics. A powerful leftist denunciation of capitalism, the picture had to be filmed in the UK, and was buried a few days after its US release by a reactionary backlash. The film is the closest an Anglo-American movie ever got to the aesthetic and socialist outlook of Italian neo-realism. My review of the movie last Easter is here.

Author: Tony D'Ambra

Hôtel du Nord (France 1938): Arletty as femme noir

Marcel Carne’s Hotel Du Nord is seen as part of a trilogy that encompasses two other of his films from the 1930s: Le quai des brumes (Port of Shadows 1938) and Le jour se lève (Daybreak 1939). These films represent what has been termed ‘poetic realism’, a gritty fatalistic French cycle of films seen as a precursor of the classic film noir cycle, with a male protagonist failing dismally to escape a dark past with a doomed romantic entanglement. Unlike the other two movies, Hotel du Nord is not based on a script from Carne’s famed collaborator, Jacques Prévert, but by scenarist Jean Aurenche, which some critics see as a weakness. The film has on the surface a lighter touch, and much of the dialog crackles with simple humanity, jokes and good-natured innuendo. But there are deeper layers of meaning, and these come from the screenplay.

The scenario revolves around the daily dramas of a not-so-grande hotel in downtown Paris. Amongst others, of principal interest for me are the indomitable Arletty as a b-girl shacked up with a hood, played by Louis Jouvet with world-weary elegance, who is in hiding after ratting on an accomplice. The story revolves around a botched suicide pact between a pair of young lovers, and the dénouement is driven by the arrival of Jouvet’s framed accomplice out for revenge. The whole affair plays out in front of the real Hotel du Nord and in a magnificent studio lot, complete with a canal, bridges, trams, village shops, and the Hotel, conceived by art director, Alexandre Trauner, who also worked on Carne’s masterpiece, Les enfant du Paradis (1945). Maurice Jaubert’s deeply romantic and evocative score completes the scene.

Aurenche’s script and Carne’s mis-en-scene develop a duality: the generosity and humanity of daily life versus the dark flip-side of angst, cowardice, and cruelty. Goodness nurtures healing and reconciliation, while falsity and lies breed suffering and terrible revenge. When the hood Jouvet declares his love for a young woman and failed-suicide, Renée, he proposes as ‘Robert’, the man he was before he became a criminal and who then took on another bi-polar identity to hide from his pursuer – love demands purity of intent and the grace he desperately seeks to recover – fate however, has other ideas. Jouvert as the squealer ‘Paulo’ was a shy bumbling petty-crook scared of blood, and now in hiding as ‘Monsieur Edmond’ he is a severe dandy who kills chickens for local housewives by strangling them with his bare hands. Arletty’s whore Raymonde is engaging, tolerant, and sharp, with a seeming heart of gold. But her final revenge as spurned lover is a dark act of treachery.

Raymonde survives without regrets between the sheets of a more compliant lover, Robert’s ultimate self-abnegation is absurd rather than tragic, and the final reconciliation of the young lovers in the closing scene is more fantasy than real. As dark as any noir.

Raymond Chandler: True Noir

“Yet the darkest of Chandler now appears clean-cut. Chandler evoked the spirit of noir through mood-setting and language, not cheap graphic gore. Now work that is hailed as ‘dark’ often seems close to putrid, almost unreadable…”

– Mick Hume, ‘Watching the Detectives’, AIR Magazine, March 2010, p18.

Last Friday marked the 50th anniversary of Raymond Chandler’s death. The passing of the man who wrote detective stories with poetic prose like this, “The night was all around, soft and quiet. The white moonlight was cold and clear, like the justice we dream of but don’t find”, from The High Window (1942).

Today most noir fiction reads like Spillane on crack. Many so-called noir writers are misappropriating noir by depicting violence, including sexual violence, so graphically you wonder who is the real psychopath.

I am reminded of these lines in Chandler’s Playback, where Marlowe narrates: “I picked a paperback off the table and made a pretense of reading it. It was about some private eye whose idea of a hot scene was a dead naked woman hanging from the shower rail with the marks of torture on her… I threw the paperback into the wastebasket, not having a garbage can handy at the moment.”

The Face Behind the Mask (1941): Iconic proto-noir

The Face Behind the Mask (RKO 1940 69 mins) has a strong claim to being the first true noir of the classic cycle. Until recently I like many others gave this accolade to another b-movie from a year earlier: Stranger on the Third Floor (Columbia 1940 64 mins). It is interesting that both films star Peter Lorre.

Stranger on the Third Floor was a landmark film in a number of respects. The influence of a new generation of European expatriates and of German expressionism in the genesis of film noir is clearly evident. The screenplay is by Austro-Hungarian, Frank Partos, the director is Latvian émigré Boris Ingster, and photography is by the cult noir cinematographer, Italian-born Nicholas Musuraca. Between the cheesy opening and closing scenes is a tight claustrophobic thriller, where fear and paranoia is deftly portrayed both in reality and oneiristically. The nightmare sequence in this picture has to be perhaps the best dream-scape ever produced by Hollywood. We have here strong evidence supporting the view that noirs appeared with the emergence of a wider awareness of psychoanalysis and its motifs in America in the early 1940’s. In this proto-noir the role of the subconscious is explored. A newspaper reporter, whose court testimony has condemned a taxi-driver for murder, begins to doubt the guilt of the condemned man. This anxiety feeds into paranoia about a mysterious stranger he encounters in his boarding house, triggering a guilt-fuelled nightmare about the fate of an obnoxious neighbor where his own sanity is put on trial. Ingster and Musucara, and associate art director, Albert D’Agostini, as in all the great b-noirs, use set-bound budget constraints as brilliant artifice. The Caligari-like sets and the necessary noir lighting make the dream sequence profoundly surreal and compelling. But there is not the despairing bleakness of The Face Behind the Mask.

The Face Behind the Mask was made by b-director, Robert Florey, and lensed by the under-appreciated Franz Planer. There is a true gestalt operating here, the work of this team here is much more than you would expect from journeyman Florey. The script (from a story by Arthur Levinson) is by Paul Jarrico, who was later blacklisted in the wake of the HUAC witch-hunt. What distinguishes this picture is the pervasive mood of life ransomed to chaotic fate, and the dire consequences of social exclusion and injustice. The Face Behind the Mask is an iconic proto-noir which presages the motifs of a score of later noirs. There is no redemption or hope. A bleak ending where Lorre’s protagonist must wreak his own terrible vengeance on his persecutors and fate itself heralds the coming of classic noir.

Some may say the story is pure melodrama and contrived, and this is hard to refute, but the film goes far beyond these limitations to reach a sort of pulp integrity. A young man from Europe lands in New York full of dreams and boisterous love for his new homeland. A tragedy destroys those dreams. An uncaring society built on inequality and with no safety net steers him ineluctably to a life of crime as the boss of a heist gang. He gets a chance at redemption, but his sins have to be paid for.

Lorre is powerful as a man who must battle his own decency to overcome malevolent fate. He is ably supported by b-stalwart George E. Stone, as his buddy-in-crime, with a wonderful performance from a 24-yo Evelyn Keyes as a young blind woman: her portrayal is the closest to angelic I have ever seen on film. The economy and tautness of Florey’s direction is inspired. You never actually see a robbery. The progress of Lorre’s career as hoodlum is shown in a deft montage of dramatic newspaper headlines and scenes of cops berated for their failure to bring the gang to justice – imposed by the economics of the b picture yes – but still impressive. When the tragic denouement begins to unravel, Florey and Planer give us innovative low-angle Dutch framing shots to telegraph the disturbances to come. The American dream becomes a nightmare for a man who must steal to pay for a doctor to visit his sick friend. Plus ca change plus la meme chose.

This gutsy-b with ‘body and soul’ is a must see.

Film Noir: Forthcoming Books

The Film Noir Encyclopedia (new editon)

Alain Silver; Elizabeth Ward; James Ursini; Robert Porfirio

Release Date: May 13th, 2010 Pre-Order

Film Noir, American Workers, and Postwar Hollywood (Working in the Americas)

Prof. Dennis Broe

Release Date: April 1st, 2010 Pre-Order

Historical Dictionary of Film Noir

Andrew Spicer

Release Date: April 15th, 2010 Pre-Order

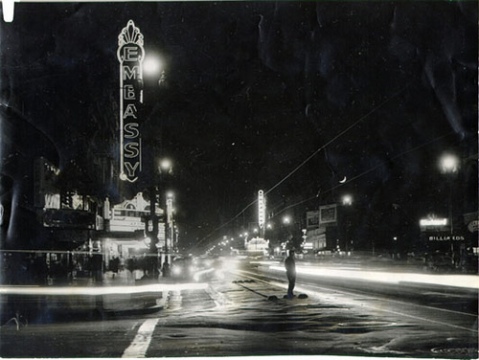

Cinematic Cities: Jersey City

All that Glitters is Gold

“The night was all around, soft and quiet.

The white moonlight was cold and clear,

like the justice we dream of but don’t find.”

Another hard luck story

Everyone’s heard them

Not many know them

Stories trodden deep down in the cracks of pavements filled with humanity’s grime

Along with the indifference and neglect that clog the dark arteries of the city’s lost soul

Dark streets cursed havens for ghostly apparitions in the shadows cast by baleful stars

High atop lamp-posts

“more die of heartache”

He knew

I know

We had a life – once

Before they took it and sold it for a quick buck

Those who own the day and make the night hell

Those who make the “hard” decisions – hard for us not for them

Those who hold all life cheap but their own

Like death – thieves in the night they steal your dreams and hock them for a fountain pen

All that glitters is gold

Summary Reviews: No Escape

Caught (1949) Max Ophuls renders the most elegant and romantic noir melodrama you will ever see. Robert Ryan, Barbara Bel Geddes and James Mason are superb in a toxic triangle of entrapment and maniacal control. Ryan is a rich nuerotic who marries Bel Geddes to prove he can, and Mason is the doctor committed to social justice who falls for her. An effective morality tale delivers a subversive plot with the integrity of commitment combating the perverting nature of greed: opulence and decency fight it out in a young woman’s soul. We can forgive the contrived resolution.

Escape (UK 1948) A hidden gem of a thriller directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz starring Rex Harrison and Peggy Cummins. Moody noir photography on fog-laden moors at night, the use of flashback, and the dire consequences of a chance encounter give it a noir dimension. Harrison is great as a toff prison escapee and Peggy Cummins (Gun Crazy) is cute as a button as an upper-class girl who falls for Harrison a la The 39 Steps.

I Can Get It for You Wholesale (1951) Abraham Polonksy’s last script before the HUAC blacklist destroyed his career. A solid drama about the NY garment business, directed by Michael Gordon and starring Susan Hayward, Dan Dailey, and George Sanders. A soft ending mars an otherwise acid critique of naked ambition and the American dream.

Night Editor (1946) A sexually charged cult noir starring the queen of b-movies Janis Carter as a rotten rich dame who double-crosses her cop lover in a story exposing the lurid morals that sometimes accompany privilege. The dialog is heavy with sexual metaphors and the repartee ‘hard-boiled’. One scene where Carter begs to see the bashed body of young woman is one of the most explicit portrayals of sexual psychosis in any noir. The atmosphere created by director Henry Levin and DPs Burnett Guffey and Philip Tannura is dark and claustrophobic. Solid entertainment and downright fun to watch. The only weakness is the framing of the story inside a wider newspaper at night theme and the feel-good ending – the movie was a pilot for a movie series which did not proceed.

Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1948) Edward G Robinson is magnificent as a man trapped by an accursed gift. Redemption is a zero sum game. A moody and deeply unsettling film based on the Cornell Woolrich novel. The deeply intelligent script by Jonathan Latimer and Barré Lyndon is more subtle and superior to Woolrich’s novel, and showcases the richness to be found in many b-movies.

Double Feature: Young Man with a Horn and A Lady Without Passport

I like to think here at FilmsNoir.Net, readers are made aware of movies that are under the radar and do not fit established categories, genres or movie lists. Many such films were made by major studios on modest budgets and while not likely to make best-of listings or have major genre standing, they are pictures that are good entertainment made with craft and discipline, and sometimes with special elements that reward the discerning viewer.

Two such films were made in 1950 and, while having noir aspects, are largely entertainment features made memorable by facets that have been largely ignored by film reviewers and other writers on film.

Young Man with a Horn from Warner Bros. was directed by Michael Curtiz, and Joseph H.Lewis directed A Lady Without Passport which was produced by MGM.

Each of these films is special in its own way.

Young Man with a Horn is loosely based on the biography of jazz trumpeter Bix Beiderdecke: the story of how a lonely kid in L.A. learns the trumpet from a black musician, who becomes his close friend and mentor. His shift to New York in pursuit of a career is the stuff of melodrama; young guy makes good, marries the wrong woman and abandons his friends, and after tragedy finds a kind of redemption. There is great jazz played by Hoagey Charmichael and Harry James, nice songs from a young Doris Day, solid acting from Kirk Douglas in the lead, Lauren Bacall as the wife, Junco Hernandez as the black trumpeter, and Charmichael as Douglas’ piano-playing buddy. Competent direction by Curtiz and inspired cinematography from DP Ted McCord also add value. Of particular interest is Baccall’s acid performance as the neurotic wife.

But the real strength of the film is in the script by Carl Foreman (who during filming of his script for High Noon in 1951 appeared at HUAC and was later blacklisted by Hollywood studio bosses). Redemption for the young man with the horn comes from a realisation that a great artist’s obsession with his craft is not the only requirement for artistic fulfilment – it cannot come from a sterile wedding of player and instrument but ultimately from a deeper maturity which comes from embracing human relationships and commitment – a responsibility to and for others.

The tragic aspect of the story lends a true pathos to the melodrama, and the prominence given to the black father-figure in a film of this era is a revelation. Here we have a powerful expression of the personal and the social filmed with empathy and commitment.

A Lady Without Passport is ostensibly a police procedural, one of the many that began to emerge in the early 1950’s as the noir cycle began to explore other directions, after the success of on-the-street exposés such as Jules Dassin’s The Naked City. Director Joseph H. Lewis made his seminal noir, Gun Crazy, in 1950, and as the noir cycle began to decline, he directed perhaps the best 50s noir, The Big Combo, in 1955. These two classic films noir established Lewis’ reputation as an innovative and iconoclastic film maker. In A Lady Without Passport he has a more prosaic script, but together with his DP Paul Vogel and a romantic score from David Raksin, he brings to the project a wonderful transforming elegance to a fairly routine story. Also unusually for Lewis, in this movie, violence is handled with restraint, but not without originality.

A U.S immigration agent played by John Hodiak is sent to Cuba to investigate the murder in New York of an illegal alien, and uncovers a people-smuggling racket run by a suave villain played by George Macready. The agent falls for a Viennese refugee played with understated angst by 35-yo Hedy Lamarr, who was then entering the decline of her career. There is romance, humour, intrigue and sensuality – the stuff of a minor Casablanca, but filmed with a casual elegance that enthralls as well as entertains. The charm of pre-revolutionary Havana is rendered with a calm detachment and the sympathetic portrayal of Latin life is boisterous yet respectful.

Much has been written of the bank robbery scene in Gun Crazy shot from within the getaway car, but equally arresting is a long take for the opening scene of A Lady Without Passport from inside a taxi. While less tense the shot is more fluid when compared with the Gun Crazy take. Indeed, Lewis in A Lady Without Passport displays the élan of Max Ophuls, with his camera often on the move, and zooming, turning and panning, as well as placed at unusual angles. In one scene an exotic cabaret dancer is filmed by placing the camera at a low angle near the floor so that the viewer is in the position of voyeur, looking up at the dancer’s legs and hips as she dances. A particularly stunning scene towards the end shows the crash of a plane and a violent killing as seen from the cockpit of a government plane that was in pursuit, with a running commentary radioed to base by the pilot. This technique gives a strong documentary feel to the whole scene and a sense of stricken helplessness. The dénouement in a foggy swamp is very reminiscent of Gun Crazy, and what it lacks in tension is made up in the artistry of the photography.

The picture’s final scene has the government agent make a radical re-statement that is sufficiently subversive to underline the human element of the story free of any romantic allusions.

Two fine Hollywood movies.

David Goodis…To A Pulp

David Goodis… To A Pulp, a film biography of noir writer David Goodis, premieres this Friday, March 5, in Philadelphia. For film-maker Larry Withers making the movie was a peak into the once-hidden life of his mother, Elaine Astor, who had previously been married to Goodis. Read all about it at Mike Lipkin’s Noir Journal.