“Between the Great Depression and the start of the Cold War, Hollywood went noir, reflecting the worldly, weary, wised-up under current of midcentury America. In classics such as Laura, Sweet Smell of Success, and Double Indemnity, where the shadows of L.A. and New York pulse with killers, corpses, and perilous romance, failure is not only a logical option but a smart-talking seduction.” – Ann Douglas, Vanity Fair March 2007

The dark night of forsaken city streets, vistas of blissful angst and unholy pilgrimage. I have been there and known their inhabitants: deadly dames, drunken losers, dangerous hoods, crooked cops, dreamers of broken dreams, and flawed heroes.

LA, Frisco, Chicago, and New York. I know these cinematic cities though I have never been. A resident knows his locale, but the city in its ectoplasmic center is not reached corporeally, only in the phantasmagoria of a thousand and one shards of shattered night. Luminescent environs of a cosmic b-movie. Wet asphalt, fog-laden piers, deserted streets, rusting hulks at anchor, the neon glimmer of purgatory dives, cigarettes and booze, dark tenements, the skid of car tires, and the wailing sirens of the dead. Staccato rhythms and aching horns, crowded pavements and desperate loneliness.

One more fix, the last heist. Treachery, misplaced loyalty, and courageous infamy. The denizens of a nether world trafficking in sordid magic and lurid hopes.

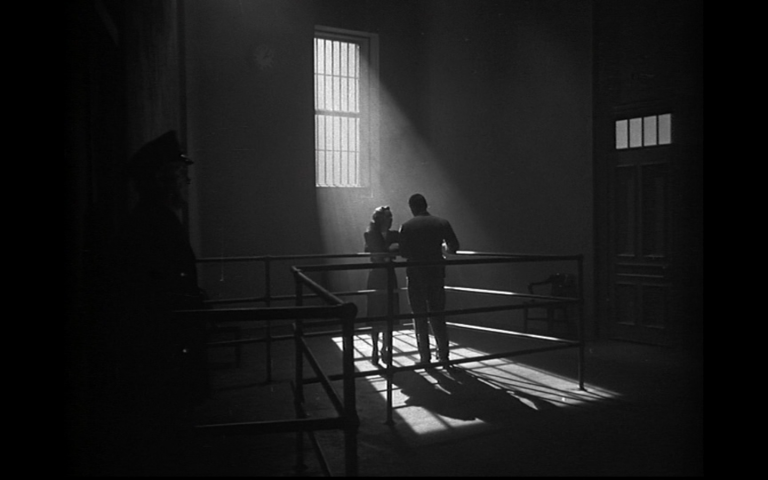

A kiss before dying, the desperate lurch before oblivion, and the erotic click-clack of stilettos on pavement. Dank stairwells and silent corridors. Closed doors and hidden secrets. You break in and fall into a bottomless pool of black. Cut to a bare light-bulb burning on a current wired from hell. Lying on a steel-framed bed you stare through the bars of perdition at yourself a wraith in a cracked mirror on the ceiling.

Film noir is a cycle of mainly American films of the 1940’s and 1950’s exploring the darker aspects of modernity, and usually set in a criminal milieu or exploring the consequences of a criminal act.

Film noir is not only for film buffs and academics. The film-makers of the 40’s and 50’s were not making “film noir” movies, they were making pictures for a wide audience which are still immensely entertaining. The movies of the classic noir cycle were subversive and questioned the facade of everyday life in stories that had wide appeal. They retain their popularity, firstly because the noir themes and motifs have universal appeal: films noir are about the individual in a hostile universe, and in the best noirs, the anti-hero has at least a shot redemption. Secondly, they are so well-made with a craft and discipline we don’t often see anymore.

Movies are essentially entertainment and commodities produced for profit. Somehow, this endeavour has produced and continues to produce films that not only have wide appeal but value as works of art to a lesser or greater degree. The great films noir had both popular appeal and artistic merit because their themes address the human condition and the frailty of normal lives, which at any moment can be plunged into the chasm of chaos, through chance or individual action – innocent or otherwise. How moral ambivalence, lust, love and greed can destroy lives was explored outside the closed romantic realism of mainstream movies.

While many see film noir originating in post-WW2 trauma, I believe the origins of film noir lie largely elsewhere. Film noir was a manifestation of the fear, despair and loneliness at the core of American life apparent well before the first shot was fired in WW2. This is not to say that the experience of WW2 did not influence or inform the themes and development of the noir cycle in the post-war period. The origins of film noir and why it flowered where and when it did are complex, and we can’t be definitive, but it is fairly evident that noir emerged before the US entered the War, and had its origins principally in the new wave of émigré European directors and cinematographers, who fashioned a new kind of cinema from the gangster flick of the 30’s and the pre-War hard-boiled novels of Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, James M. Cain, and Cornel Woolrich. We can also clearly see the influence of German expressionism, the burgeoning knowledge of psychology and its motifs, and precursors in the French poetic realist films of the 30’s. Noir was about the other, the “dark self” and the alienation in the modern American city manifested in psychosis, criminality, and paranoia. It was also born of an existential despair which had more to do with the desperate loneliness of urban life in the aftermath of the Depression. Noir writer Cornell Woolrich, for example, was a lonely and repressed individual, who spent his life in hotel rooms, and painter Edwards Hopper’s study of the long lonely night in Nighthawks was painted in 1942.

In the first ever book about film noir, A Panorama of American Film Noir, 1941-1953, published in France in 1955, and only translated into English in 2000, the authors, Raymond Borde and Étienne Chaumeton, in seeking to explain why films noir appeared, saw as a major influence the emergence of a wider awareness of psychoanalysis and its motifs in America at the time. Their analysis of their canon of the first big three post-war noirs was centered on the films’ dream-like qualities and the emergence of protagonists with pronounced psychoses: The Big Sleep (1945), Gilda (1946), and The Lady From Shanghai (1947).

Also there were elements of the socio-political in many noirs: early noir directors Abraham Polonsky, Jules Dassin, Fritz Lang, and Billy Wilder come immediately to mind. Many of the great European film noir directors that landed in Hollywood, fled fascism, and had leftist views. While the leftist critique of the intellectual left of Europe was a response to existentialism, the response of others was an inclination to nihilism, and we can see nihilism too in many noirs of the classic cycle.

Principally in film noir, it is the narrative and existential angst that drives a mostly male protagonist, who more often than not is the victim of a manipulative femme-fatale. The post-war anxiety of film audiences can help explain the popularity of the films, but I think Ann Douglas in her piece in the March 2007 issue of Vanity Fair takes us further: “Noir is premised on the audience’s need to see failure risked, courted, and sometimes won; the American dream becomes a nightmare, one strangely more seductive and euphoric than the optimism it repudiates… Noir provided losing with a mystique.”

In America it is the anxiety of being a “loser” that underlies male existence more than the experience of war. The male archetype in film noir is an outsider. The great noir novels, The Maltese Falcon (1941) and The Big Sleep (1945), for example, that were brought to the screen in the 40s, were written before WW2 in the 1930’s, and cannot be understood by reference to post-war trauma. Consider also Out Of The Past (1947) and The Big Heat (1953). In both movies, the male protagonists are clearly outsiders. Jeff Bailey in Out of the Past tries to be rid of his past in a small town but his outsider status is firmly established from the outset before he even appears on the screen, and in The Big Heat, honest cop, Dave Bannion, is not helped by fellow cops in his fight against corruption. These men are outsiders also in the fuller European sense, and it is no coincidence that the directors, Jacques Tourneur and Fritz Lang, were émigrés from Europe. The Walter Neff character in Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944), holds down a middle-class job and is respected by his colleagues, but he is a loner. When Neff falls for femme-fatale, Phyllis Dietrichson (played by the great Barbara Stanwyck in a blonde wig), he is not only seduced by her allure, but by his loneliness. A man can fatally love a woman he does not quite trust, because he desperately wants to believe otherwise, and fears being alone again more than the fateful consequences of his attachment.

The general consensus is that the first film noir was, Stranger on the Third Floor (1940), an RKO b-movie of only 64 minutes, which was a landmark film in a number of respects. The influence of a new generation of European expatriates and of German expressionism in the genesis of film noir is clearly evident. The screenplay is by Austro-Hungarian, Frank Partos, the director is Latvian émigré Boris Ingster, and photography is by the cult noir cinematographer, Italian-born Nicholas Musuraca. With b-actors as leads, the movie is propelled by the intelligence of the script, the strength of the direction and cinematography, and excellent turns by Peter Lorre as the Stranger and Elisha Cook Jr. as the taxi-driver accused of murder. Between the cheesy opening and closing scenes is a tight claustrophobic thriller, where fear and paranoia is deftly portrayed both in reality and oneiristically. The nightmare sequence in this picture has to be the best dream-scape ever produced by Hollywood. Here we have the strongest evidence supporting the thesis set out in A Panorama of American Film Noir, that films noir appeared with the emergence of psychoanalysis in America in the early 1940’s. In this proto-noir, we see explored the role of the subconscious, where reporter Mike, whose testimony sways the jury, starts to question the guilt of the condemned taxi-driver, after his girl-friend Jane tells him she has a “feeling” that the jury has condemned an innocent man. This doubt then feeds into Mike’s paranoia about the mysterious stranger he encounters in his boarding house, and a guilt-fueled nightmare about the fate of an obnoxious neighbor where his own sanity is put on trial. The film’s makers, as in all the great b-noirs, use set-bound budget constraints as brilliant artifice. The Caligari-like sets and the necessary low-key noir lighting make the dream sequence profoundly surreal and compelling, and the climax towards the end of the film on a tenement street set late at night, builds and sustains the fear and tension in a way that even in a big-budget movie would be hard to emulate.

I consider a movie a film noir if it has a “noir sensibility”. This sensibility must have a redemptive focus for me to value a film, whether redemption is achieved or not. This is what the great films noir have in common: a profoundly and deeply human response to the chaos and random contingency at the edge of existence. Such films include Robert Wise’s The Set-Up (1949), Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944), Robert Siodmak’s The Killers (1946), Jacques Tourneur’s Out Of The Past (1947), Joseph H. Lewis’s The Big Combo (1955), and Jules Dassin’s Thieves Highway (1949).

Although The Maltese Falcon (1941) is perhaps my all-time favorite movie, it goes beyond the boundaries of film noir, so I would have to say my favorite films noir are Raw Deal (1948) and The Set-Up (1949).

The Set-Up from the RKO studio, directed by Robert Wise and starring Robert Ryan, is a sharp expose of the fight game packed into a lean 72 minutes. Filmed at night on a studio lot, this movie is brooding and intense, with Robert Ryan, as the aging boxer, “Stoker” Thompson, in perhaps his best role. The boxing scenes are as real as they get. Ryan himself was a college boxing champ. The arena is brilliantly filmed with focused and repeated shots on selected spectators, which portray not only the excitement, but also the unadorned mob brutality that reaches fever pitch as the fighters struggle to a climactic finish. Early in the film, the boxers’ dressing room, where Stoker’s essentially decent persona is established from his interactions with the other boxers, is beautifully evoked. Each person in that room is deeply and sympathetically drawn, and these scenes are enthralling. To the movie makers’ credit, remember this is 1949, there is a black boxer, who responds to Stoker’s friendliness, with a heart-felt wish of good luck, after winning his own fight. The Set-Up as a real-time evocation of one fight, brilliantly confronts the noir theme of the melancholy duality of winning and losing. Stoker refuses to throw the fight and by winning loses when the heavies, who paid his trainer for the fall, cripple him in a dark back-alley outside the stadium. It is a simple story of gut-wrenching humanity.

Raw Deal is about a tragic love triangle very reminiscent of Marcel Carne’s classic of poetic realism, Port of Shadows (1938). It is a sublime film from director Anthony Mann and DP John Alton, with a knockout cast in a strong story stunningly rendered as expressionist art. The portrayals by Dennis O’Keefe, Claire Trevor, Marsha Hunt, and John Ireland are career bests. Poetic voice-overs by Claire Trevor are beautifully enhanced by Paul Sawtell’s eerie scoring.

In modern cinema, I would find a film has having noir elements rather than saying that it is a noir or a neo-noir. Recent movies such as Michael Clayton (2007) and In The Valley of Elah (2007) fall into this category. In Michael Clayton the veneer of respectability of modern business is stripped away to reveal corruption and moral turpitude – a perennial noir theme. George Clooney plays Michael Clayton, a “fixer” for a big NY law firm’s well-heeled clients who get into trouble. When the firm’s top litigator Arthur (Tom Wilkinson) goes off the wall, Clayton is called in to clean up, and as the story develops he is forced to confront his corrupt activities and choose loyalty to his friend and integrity, over corporate and personal survival. On the surface In The Valley of Elah is a police procedural framed against US soldiers returning from the Iraq war. On a deeper level it is an exploration of contingencies and responsibility. The war in Iraq, the killing of a child by a US humvee on the streets of Baghdad, and the gruesome murder of a returning soldier on the outskirts of an American army town, bring chaos to the life of a father, who no longer understands his son or his country and its institutions. Everything including the American flag is upside-down.

If you are new to film noir and would like to explore it further, I would start with the Wikipedia article on film noir and these books:

- The Rough Guide to Film Noir (2007) A great introduction that covers the genre from early German expressionism to the latest neo-noirs, and highlights the movies to look out for.

- Film Noir by Alain Silver (2004) A general overview of film noir covering its most important themes with many rare stills. Among the films covered are: Double Indemnity (1941), Kiss Me Deadly (1955), Gun Crazy, Criss Cross (1949), Detour (1945), In A Lonely Place (1950),T-Men, Out Of The Past (1947), The Reckless Moment, and Touch of Evil (1958).

Related Post: Re-Focusing Film Noir

Great site! Keep it up. I am an Indian Film Studies teacher and a noir-fan. Will recommend this site to my students.

LikeLike

Thanks Anindya! Feedback like yours makes it all worthwhile. Tony

LikeLike

Awesome site. I’m studying film noir at the moment and this site is incredibly helpful.

LikeLike

Thanks Marie! Glad to hear you find the site helpful 🙂

LikeLike

Excellent and comprehensive essay with many sticking points.

-wide audience appeal

– a redemptive focus of noir whether or not achieved

– existential; angst of the male protagonist

– The Setuop was an excellent expose of the fight game as well as an excellent classic

– Noir elements stand out in moddern cinema

– “accenting the random contingency at the edge of existence”

– role of emigre directors and expressionism as well as the use of light and dark shading-these are unduplicatable on the color screen

LikeLike

I enjoyed the essay very much and tried formerly to post a comment which did not seem to go through.Your points on noir stuck out in my mind. The first I pasted from the essay is below referenced:

“Film noir was a manifestation of the fear, despair and loneliness at the core of American life apparent well before the first shot was fired in WWII.” This is certainly true and represents a dark side of the American dream always lingering in the backdrop of all the noir fils, I feel.

LikeLike

Thank you very kindly Ed for your comments. I really needed a fillip today, and I am truly grateful not only for your comments here and on the other threads, but also for your valuable contribution to the discourse on those posts.

I am sorry there was a delay in your comments appearing, but the first post from a commenter is placed in the moderation queue. Future posts from you will now appear immediately.

LikeLike

Thanks pal…swell website.

You’ve pushed me beyond Borde and Chaumenton. Despite them Frenchmen taking a stab at defining film noir, I’ve been in the dark about defining the genre, living in confusion and shadows for years. Trying to define pulp noir and film noir gives me awful headaches sometimes, like a bad highball hangover. But your noir remedy seems to help.

There I go again…offering praise, when I don’t even know you. Praise in exchange for reading your website …sounds like an even deal, I guess. Or am I somebody’s fool again? Maybe not this time. See yah pal.

LikeLike

Thanks HDB! Glad to be of service. You have style…

LikeLike

I enjoyed your interesting article. Here’s an article on The Glass Key that your readers may enjoy.

LikeLike

Thanks Eric.

LikeLike

Oh my! Awesome site which explains so well the ‘conventions’ of the genre. Thank you, it helps a lot

Kate

LikeLike

Thanks Kate!

LikeLike

Extremely well written, Tony, and as an English prof., I know my stuff. Out of the Past is on TCM tonight, and I wanted a good explanation of film noir, which you provided–artfully. Let me know if you are able to edit ( not biggies), and I’ll tell you where to look. Read carefully. You should be able to find the spots yourself.

Keep writing. You’re exceptionally talented!

LikeLike

Thanks Joyce. I am painfully aware of my shortcomings as a writer. I wrote this nearly three years ago, and it certainly needs revision. Any insights you have will be welcome. Tony

LikeLike

Thanks for your site, I love how you have been so loyal to the genre. I am a fan too of noir. Some of my favorite titles are: “Pickup on South Street” and “Quicksand”. Thanks for your major contribution to the effort of keeping noir alive and well!

LikeLike

Thanks Juan. Great to have feedback like yours. Tony

LikeLike

Very informative and entertaining essay. I have recommended it to both students and colleagues on many occasions.

LikeLike

Thanks Leo! Tony

LikeLike

This is a great book explaining the origins of Film Noir – Blackout: World War II and the Origins of Film Noir by Sheri Chinen Biesen (Oct 19, 2005), and its given me some new insight into what I’m trying to quantify Hard Core/Soft Core Film Noir. I suggest everyone read it. Some quotes from the book below.

A number of elements all came together into what The New York Times tagged the “red meat crime cycle” (before French critics coined the term Film Noir) at the onset of WWII. “The PCA’ s lapses in code enforcement, the Office of Censorship banning “un-American” Hollywood gangsters but condoning of depictions of war related atrocities, and the Office of War Information’s regulation of screen stories depicting the combat front or domestic home front to promote the war effort—all of these developments complicated WWII censorship and encouraged hard-boiled film adaptations that initially reformed gangsters and promoted patriotic crime.” Pictures were filmed with “tremendous studio rationing of lighting, electricity, film stock, and set materials” in an uncharacteristically dark urban Los Angeles basin in response to wartime blackouts.

The first Noir where all of the elements came together was Double Indemnity, and along with other wartime productions such as The Phantom Lady and, Murder My Sweet represented some of the most expressionistic, stylistically black phase of film noir (what I’m calling the *Hard Core Noirs*). “The noir aesthetic evolved from the wartime constraints on film making practices. Brooding, often brutal realism was conveyed in low lit images recycled sets (disguised by shadows, smoke, artificial fog, and rain), tarped studio back lots, or enclosed sound stages.

In the post war period film makers redefined noir realism having more flexibility in location shooting and lighting. Wartime Noir created a psychological atmosphere that in many ways marked a response to an increasingly realistic and understandable anxiety—about war, shortages, changing gender roles, and “a world gone mad”—that was distinctive from the later postwar paranoia about the bomb, the cold war, HUAC, and the blacklist which was more intrinsic to the late 40’s and 50’s Noir pictures.” (lighter grayer or Films Gris, *Soft Core Noir*)

And you can see this in the films. Wilder’s Double Indemnity is darker in visual style than 1950’s Sunset Boulevard, Fritz Langs Ministry of Fear and Scarlett Street are darker than The Big Heat (1953). But there are some exceptions Aldrich’s *Kiss Me Deadly*(1955) and Lewis’ *The Big Combo*(1955) are pretty dark, and *Kiss of Death* is sort of a hybrid the first 2/3rd’s is visually gray but the last 1/3 after Tommy Udo is acquitted plummets nicely into the shadows, but the general trend outlined in the book is distinctive and sort of explains the reason for the range in the pallet of what is currently defined as Films Noir.

LikeLike

PS I’m currently comprising a list of the darkest of the Noirs films that seem to be filmed in a world of perpetual night, from the Classic Noir period (the Hard Core Noir) so far these are the films (that I’ve seen that fit the list.

The Big Combo

Crime Wave

Raw Deal

The Asphalt Jungle

He Walked By Night

Criss Cross

The Narrow Margin

Night And The City

Crossfire

Red Light

They Live By Night

Where Danger Lives

The Set Up

The Phantom Lady

Scarlett Street

Detour

The Window

99 River Street

Killers Kiss

The Killers

Double Indemnity

T Men

The Killing

Dead Reckoning

The Crooked Way

Edge of Doom

The Dark Corner

Where The Sidewalk Ends

Kiss Me Deadly

Sudden Fear

Looking forward to any additions/suggestions

LikeLike

Dear Sir I collect feature films on 16mm. And have recently turned my attention to film-noir.I own “Spiral staircase”(1946) aand am in the process of purchasing “The Killers”.I occassionally I screen a film with my local ppop-up cinema

LikeLike

Thanks Christopher for your visit. Interesting to hear about your collection.

LikeLike

Nicely told. I am the writer of German Expressionism, Film-noir and Sir Fritz Lang. You should also describe the film noir more in detail. My book will also help you.

LikeLike

As an amateur fan who relys on the streaming services in the UK, thanks for a very useful site.

LikeLike

Thanks! Great to know you found the site of interest.

LikeLike

Hey, I’m from Brazil and I love know about movies and the many ages of cinema. Thanks for this website, your job is great! I love the lists! Ty!!

LikeLike

Obrigado Renan! Much appreciated 🙂 Tony

LikeLike

I have recently purchased a 16mm print of”touch of evil “(1958) Marlene Dietrich is simply beyond brilliant in this film

LikeLike