“if i had been a ranch, they woud have named me ‘Bar Nothing’ …”

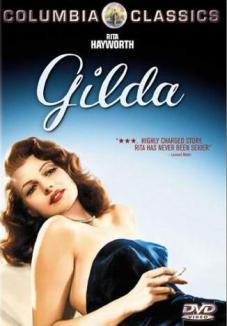

Aptly titled, this film is all about Rita Hyaworth’s Gilda: forget the weak story and the plot holes, just marvel at the beauty and charisma of this woman. She dances, she struts, she pouts, and she acts with passion and flair!

And forget it if you are looking for a film noir: it is not. As a film it ranks with flawed gems like Beat The Devil – it just doesn’t add up but you have a helluva time anyway.

Could you explain what are some essential elements/ingredients of film noir that exclude Gilda from that category? I’ve seen it included in the genre multiple times, as well as Gilda’s image on the cover of film noir books, as if it’s a sort of prime example of the genre.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment Zac. I wrote this before I read your review of Gilda 🙂

Gilda was first identified as a noir by Borde and Chaumeton in their seminal, A Panorama of Film Noir 1941-1953 (1955): “within the noir series Gilda was a film apart, an almost unclassifiable movie in which eroticism triumphed over violence and strangeness.” – see http://tinyurl.com/4a7lla for a fuller extract.

From my “What is Film Noir” FAQ: “[Borde and Chaumeton] in seeking to explain why films noir appeared, saw as a major influence the emergence of a wider awareness of psychoanalysis and its motifs in America at the time. Their analysis of their canon of the first big three post-war noirs was centered on the films’ dream-like qualities and the emergence of protagonists with pronounced psychoses: The Big Sleep (1945), Gilda (1946), and The Lady From Shanghai (1947).”

Essentially I don’t see Gilda as a noir as it lacks a noir sensibility: a sense of the chaos and contingency at the edge of existence. I don’t apply a template to films considered noir and don’t believe noir is a genre.

This is a good summary of the debate about the meaning of “film noir” from Encyclopedia of Film Noir (2007) By Geoff Mayer, Brian McDonnell:

“Film noir is more than just 1940s and 1950s crime films infused with a higher quotient of sex and violence than their 1930s counterparts. There is, however, as Andrew Spicer (2002) argues, a prevailing noir myth that “film noir is quintessentially those black and white 1940s films, bathed in deep shadows, which offered a ‘dark mirror’ to American society and questioned the fundamental optimism of the American dream.” There is, of course, some truth contained in this so-called mythology, although it is more complex than this. Film noir is both a discursive construction created retrospectively by critics and scholars in the period after the first wave of noir films (1940–1959) had finished, and also a cultural phenomenon that challenged, to varying degrees, the dominant values and formal patterns of pre-1940 cinema… This delineation between the 1930s and 1940s brings us back to the question, What is film noir? Silver and Ursini (2004) address this issue by dividing noir into separate formal, thematic, and philosophical elements. Out of this, they argue, a movement called “film noir” emerged with the 1941 version of The Maltese Falcon, as discussed previously. However, as Steve Neale (2000, 173) argues, as “a single phenomenon, noir . . . never existed.” Many of its so-called characteristic features, such as the use of voice-over and flashback, the use of high contrast lighting and other expressionist elements, the downbeat endings, and the culture of distrust between men and women, which often manifested itself in the figure of the femme fatale, are “separable features belonging to separable tendencies and trends that traversed a wide variety of genres and cycles in the 1940s and early 1950s” (p. 174). Neale (2000, 174) concludes that [any] attempt to treat these tendencies and trends as a single phenomenon, to homogenise them under a single heading, “film noir,” is therefore bound to lead to incoherence, imprecision, and inconsistency—in the provision of the criteria, in the construction of a corpus, or in almost any interpretation of their contemporary sociocultural significance. Film noir, as we know, is unlike other studies of Hollywood genres or cycles as it was not formed out of the usual sources such as contemporary studio documents. It is, in essence, a discursive critical construction that has evolved over time. However, despite its imprecise parameters and poorly defined sources, it is, as James Naremore (1998, 176) points out, a necessary intellectual category, for if “we abandoned the word noir we would need to find another, no less problematic, means of organizing what we see.” The contemporary term used by reviewers to describe films now classified as noir was melodrama—as Steve Neale (1993) points out in his intensive survey of American trade journals from 1938 to 1960, nearly every film noir was labeled or described in the trade press as some kind of melodrama. This included key films such as The Maltese Falcon (1941), This Gun for Hire, Phantom Lady, The Postman Always Rings Twice, The Killers, Scarlet Street, Detour, Gilda, Raw Deal, Out of the Past, and many other detective, gothic, gangster, or horror films enveloped by the noir label. The reviewers, in an attempt to signify that these films were somehow different from other Hollywood melodramas, often attached the terms psychological,psychiatric, or even neurotic to the melodrama—this included films as diverse as White Heat, This Gun for Hire, My Name Is Julia Ross, The Gangster, High Wall… “

LikeLike

“Gilda, are you decent?”

“Me?…sure, I am decent.” Gilda throwing back her hair.

I disagree. She’s fantastic!

Rita (Gilda) is one hell of a dame in this south of the boarder flick. And I don’t care what Michael O’Hara and Bannister think of Rita. Why, I’d paint this dame on the side of my B-17 bomber.

LikeLike