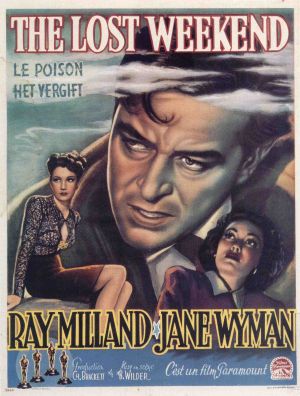

In the seminal August 1946 article which coined the expression ‘film noir’, French film-critic Nino Frank referred to five Hollywood movies as noirs: The Maltese Falcon (1941), Double Indemnity (1944), Laura (1944), Murder, My Sweet (1944), and The Lost Weekend (1945). By coincidence in the same month, expatriate German cultural critic, Siegfried Kracauer, who had moved to America because of WW2, in Commentary magazine argued that Hollywood films like Shadow of a Doubt (1942), The Lost Weekend (1945), and The Stranger (1946), displayed a certain decadence.

In the first book on film noir, A Panorama of American Film Noir, 1941-1953, published in France in 1955, the authors, Raymond Borde and Étienne Chaumeton, say that The Lost Weekend was only superficially a film noir, because “strangeness and crime were absent”. In Andrew Spicer’s Film Noir (2002), The Lost Weekend does not rate a mention, and it does not merit an entry in Silver and Ward’s Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference (1992).

To my mind Billy Wilder’s The Lost Weekend is unequivocally a film noir. The film has a definite noir sensibility and explores the dark themes of existential angst and entrapment. While the story arc is about an alcoholic’s weekend bender which spirals out on to the edge of desperate criminality, and the portrayal of alcoholic addiction was strong enough for the liquor industry to offer Paramount a cool five million dollars to bury the picture, the underlying theme is the angst of failure, of being trapped in a life without purpose or meaning. Ray Milland is Don Birnam, a failed writer, hanging on a thread like the bottle of Rye hidden and hanging on a cord outside his bedroom window, and nothing can more powerfully express his life than when he tells his girl, Helen, why he drinks (and this excerpt from the script is testimony to the power of the screenplay penned by Wilder and long-time collaborator, Charles Brackett):

DON:

A writer. Silly, isn’t it? You see, in college I passed for a genius. They couldn’t get out the college magazine without one of my stories. Boy, was I hot. Hemingway stuff. I reached my peak when I was nineteen. Sold a piece to the Atlantic Monthly. It was reprinted in the Readers’ Digest. Who wants to stay in college when he’s Hemingway? My mother bought me a brand new typewriter, and I moved right in on New York. Well, the first thing I wrote, that didn’t quite come off. And the second I dropped. The public wasn’t ready for that one. I started a third, a fourth, only about then somebody began to look over my shoulder and whisper, in a thin, clear voice like the E-string on a violin. Don Birnam, he’d whisper, it’s not good enough. Not that way. How about a couple of drinks just to put it on its feet? So I had a couple. Oh, that was a great idea. That made all the difference. Suddenly I could see the whole thing – the tragic sweep of the great novel, beautifully proportioned. But before I could really grab it and throw it down on paper, the drink would wear off and everything be gone like a mirage. Then there was despair, and a drink to counterbalance despair, and one to counterbalance the counterbalance. I’d be sitting in front of that typewriter, trying to squeeze out a page that was halfway

decent, and that guy would pop up again.HELEN:

What guy? Who are you talking about?DON:

The other Don Birnam. There are two of us, you know: Don the drunk and Don the writer. And the drunk will say to the writer, Come on, you idiot.

Let’s get some good out of that portable. Let’s hock it. We’ll take it to that pawn shop over on Third Avenue. Always good for ten dollars, for another drink, another binge, another bender, another spree. Such humorous words. I tried to break away from that guy a lot of ways. No good. Once I even bought myself a gun and some bullets. (He goes to the desk) I meant to do it on my thirtieth birthday. (He opens the drawer, takes out two bullets, holds them in the palm of his hand.)DON:

Here are the bullets. The gun went for three quarts of whiskey. That other Don wanted us to have a drink first. He always wants us to have a drink first. The flop suicide of a flop writer.WICK [Don’s brother]:

All right, maybe you’re not a writer. Why don’t you do something else?DON:

Yes, take a nice job. Public accountant, real estate salesman. I haven’t the guts, Helen. Most men lead lives of quiet desperation. I can’t take quiet desperation.

To complete the potent formula you have the cinematography of the great John F. Sietz, art direction by the brilliant Hans Dreier, and a deeply evocative score from Miklós Rózsa. Sietz’ fluid and lengthy takes, and moodily lit interior shots add depth to the ‘caged’ mise-en-scene of Don’s apartment: evoking a sense of desperation when Don ransacks the place searching for a bottle of Rye; and then terror at night when the DT’s take hold. On the streets of Manhattan, Sietz’ camera is in deep focus on harsh sun-lit streets of empty desperation where a staggering Don searches for an open pawn shop on Yom Kippur. Drieir elegantly furnishes Don’s tenement apartment with bookcases, sofas, lamps, and wall-hangings that disguise the places where he hides his booze. Rózsa’s score is persistent and dramatic, and he innovatively uses the early electronic instrument, the theremin, to produce an eerie and sinister motif for Don’s affliction.

Milland’s performance is masterful and he carries the picture. Cast against type, his tranformation from a clean-shaven everyman to a dishevelled drunk hallucinating in a darkened room, where his eyes betray the depth of his obsessed decline, is fully dramatic in it’s intensity. Jane Wyman as Helen, only comes into her own in the finale after she has lost a leopard-skin coat and her hair is wet and loose after being in the rain. Minus the coat and her perm she is a sensual and liberating influence. To Wilders’ and Brackett’s credit, the ending while positive remains open-ended: a relapse is just as likely as Don actually writing the great unfinished novel. A solid contribution is made by b-actors Howard Da Silva and Doris Dowling. Da Silva plays a sympathetic bartender who is a father-confessor figure ironically dispensing shots of rye instead of Hail Maries. Dowling, who played the murdered wife in The Blue Dahlia (1946), is particularly engaging as a b-girl who is soft on Don. Veteran noir supporting actor, Frank Faylen, has a short but memorable appearance as a male nurse in a hospital drunks clinic. This harrowing sequence is shot in true noir style and with a frankness that works brilliantly to enlarge the drama from the particular to the social. The only weakness is a wooden portrayal of Don’s straight-laced brother.

This brings me to a particularly intriguing element in The Lost Weekend. Don is not a lecherous drunk: his desire for booze sublimates all other appetites, but interestingly Wilder weaves a stunning sexual frankness into the photoplay. The b-girl Gloria works out of Stan’s bar, and the nature of her work is up-front and personal. The male nurse, Bim, in the detox clinic is clearly gay, and his sermonising on the evils of drink has a surreal even sinister quality.

Early in the movie in an interlude told in flashback Wilder’s sardonic humor takes center stage. Don is at the Opera, and all on stage are drinking champagne. The whole sequence plays as a liquor ad tempting Don to leave the performance and try and grab hold of a bottle of rye in the pocket of his checked-in overcoat.

A great Hollywood picture and a true noir.

A wonderful review, Tony. You make a perfectly solid case for this picture being a film noir in this engaging and intelligent look at Billy Wilder’s Oscar-winner.

LikeLike

I think this may be my new favorite post from this blog. You offer an extremely compelling look at the subterranean themes and motifs of a classic which I’ve actually yet to see. But based on your descriptions, and the quotes you selected, I’m now itching to see it, much as Ray Milland apparently itches for that one more drink…

LikeLike

To be perfectly honest I always considered this film (despite it’s awards and wide-acclaim) as a minor Wilder, a film that badly-dated (it was admittedly the first film to take on alcoholism) and showcased a character that was extremely unpleasant from the very beginning of the film. I found it hard to warm up to him, but I’ll still admit that (as Tony notes here) that this is well-made picture technically, and it has solid acting all-around and impressive location shooting on NYC streets. In a very week year in Hollywood, as the war ended, this film somehow edged ahead of Hitchcock’s SPELLBOUND, and Cutiz’ MILDRED PIERCE (as well as the GOING MY WAY “sequel”) to capture the Best picture Oscar and some critics’ prizes. I do remember that Pauline Kael dismissed it by saying it “lacked fluidity” and that the slowly paced scenes were “overcalclated” and “lacked imagination.”

But there’s no denying that several contributions still make the viewing of the film irresistible, including the central performance by Ray Milland, which tony rightly celebrates. I guess we could say that Milland’s acting is so effective that we loathe the character he play so intensely.

Here’s what Tony says about that central performance with acute observation: “Milland’s performance is masterful and he carries the picture. Cast against type, his tranformation from a clean-shaven everyman to a dishevelled drunk hallucinating in a darkened room, where his eyes betray the depth of his obsessed decline, is fully dramatic in it’s intensity.”

That’s quite a description there, and it does prove at least on that count that there is no dating when it comes to that kind of brilliance, much in the same way that Charles Laughton’s great performance transcended the time trappings of his THE PRIVATE LIFE OF HENRY VIII. Similarly, I don’t think another viewing of THE LOST WEEKEND would diminish Jane Wyman’s effective subservience, nor the supporting turns of Howard da Silva or Doris Dowling.

I caught the excitement in this piece about the noir style being evident in the hospital scene, and much appreciated that ‘sexual frankness’ discourse in describing its underpinnings.

I must say that I couldn’t agree with Mr. D’Ambra any more than I do about the great composer Miklos Rosza, who rarely contributed a weak score. Mr. D’Ambra notes the “sinister motif for Don’s affliction” and in a larger sense a “persistant and dramatic score.” He’s right. It’s not Rosza’s best work (BEN-HUR and SPELLBOUND represent his top-level among others), but it renders THE LOST WEEKEND the right accompaniment.

I will come down again on Tony’s side as to the ending. Brackett and Wilder were wise to avoid contrivances or a maudlin conclusion to what was a most serious film at the time of its release. Now, with all the attention to social issues and addictions, this ‘tame’ film can almost be seen as an after thought.

Perhaps the most superbly rendered passage in this review (which must surely rank in length and perceptiveness as one of Mr. D’Ambra’s best ever) is the discussion of John F. Sietz’s extraordinary cinematography:

“To complete the potent formula you have the cinematography of the great John F. Sietz, art direction by the brilliant Hans Dreier, and a deeply evocative score from Miklós Rózsa. Sietz’ fluid and lengthy takes, and moodily lit interior shots add depth to the ‘caged’ mise-en-scene of Don’s apartment: evoking a sense of desperation when Don ransacks the place searching for a bottle of Rye; and then terror at night when the DT’s take hold. On the streets of Manhattan, Sietz’ camera is in deep focus on harsh sun-lit streets of empty desperation where a staggering Don searches for an open pawn shop on Yom Kippur. Drieir elegantly furnishes Don’s tenement apartment with bookcases, sofas, lamps, and wall-hangings that disguise the places where he hides his booze.”

All I can say to that paragraph is WOW! That really brings the film back into focus, even if it’s been years!

At the end of the day (and the exerpts from Brackett’s screenplay there were fascinating to look at again!) we can look to Mr. D’Ambra himself to offer the defining placement of this film in the pantheon of film noir, even if on another level it’s about an alcoholic. Here’s what Mr. D’Ambra says to qualify it: “To my mind Billy Wilder’s The Lost Weekend is unequivocally a film noir. The film has a definite noir sensibility and explores the dark themes of existential angst and entrapment.”

And again, therein lie the most vital elements, folks.

LikeLike

Movie Man, I just got the validation I was looking for: This IS Tony D’Ambra’s greatest review ever!!!

I was drawn into this and couldn’t stop reading (or writing) even though this was never one of my favorites despite my great affinity for Wilder.

LikeLike

Thanks Alexander, Movie Man, and Sam. I am particularly appreciative of your support, as each of you is among those film writers on the web whom I most admire.

I am the first to acknowledge my reviews tend to be short, and this time, the richness of this film inspired me to be more ambitious. Sam, you have been inspired too in your lengthy response!

Sam, I agree that in the opening scenes Don is a real jerk and it is unsettling, but this is a legitimate scenario. Frustration is often manifested in anger and intolerance. The uncertain nature of Don’s ‘cure’ has to be established, and it is fair to say that making him unsympathetic is perhaps very canny. Just before the dialog I quote in the review, Don, in a flashback, is recovering from a heavy drinking session, when his girl, Helen, who does not know he has a habit, rings the apartment door bell. Don hides in his bedroom after asking his brother, Wick, to deal with her. Don listens while Wick concocts a story that Don is not home and that an empty bottle of Rye that roles out from under the sofa is Wick’s. We fully expect Helen to leave the apartment blissfully ignorant, but as she is about to leave, Don bursts out of his room and confesses – leading into the aforementioned dialog. This scene has a greater impact than if we had a more sympathetic view of Don initially.

LikeLike

Sam, glad I could validate (any time). I would offer one corrective to your comment, though – I can think of at least one earlier film dealing with alcoholism; D.W. Griffith’s severely underrated “The Struggle,” his last film and a startlingly realistic picture both for the time and for the director. You can read my (very impressed) review of it here:

http://thedancingimage.blogspot.com/2008/11/auteurs-dw-griffith-struggle.html

– and it’s available on Netflix on the same disc as Abraham Lincoln.

LikeLike

Movie Man, just got to this now but I will be thrilled to read your review on it. Thanks so much for that. I have the earlier release of the ABRAHAM LINCOLN, but I will at least make a copy of this njew double-feature!

LikeLike

Hi! Tony,

My friend Megan said, this about your review of director Billy Wilder’s 1945 film The Lost Weekend…Megan said,”Well done, Tony, and thank you Dee for bringing this to us!”…

…Tony,I also want to thank-you, for letting me feature your review on my blog yesterday.

I have to second Megan’s notion…Well done!

Take care!

DeeDee

LikeLike

Thanks DeeDee and to Megan!

LikeLike